By Preserve Gold Research

Something unusual is happening in the heart of U.S. fiscal policy, and few are paying attention. Beneath the surface of official statements and bond auctions, the U.S. Treasury has begun steering the economy in ways that look less like routine debt management and more like covert stimulus. By shortening the average maturity of newly issued debt, the Treasury may be suppressing long-term interest rates, delivering a jolt of monetary support that, according to economists Stephen Miran and Nouriel Roubini, could rival a full percentage point rate cut from the Federal Reserve.

This maneuver, now widely known as Activist Treasury Issuance (ATI), emerged during the Biden administration under Janet Yellen. But it’s under her successor, Scott Bessent, that ATI has grown. The implications stretch far beyond fiscal strategy. While the Fed raises rates in its fight against inflation, the Treasury is pulling in the opposite direction. The result is a growing conflict between two pillars of economic governance. This tension may prove more than academic. It could sow deeper instability, undermine anti-inflation efforts, and expose ordinary Americans to rising financial stress. In the sections that follow, we unpack how ATI works, why it’s gaining traction, and what it might mean for the economic path ahead.

What is “Activist Treasury Issuance”?

Activist Treasury Issuance is a deliberate shift in strategy—one that leans heavily toward short-term debt issuance, primarily through Treasury bills, while pulling back on longer-dated bonds. It’s a calculated attempt to shape the yield curve and to hold down long-term interest rates by quietly reducing the supply of 10- and 30-year Treasuries. In effect, its stimulus, delivered not by the Federal Reserve, but through the Treasury’s debt playbook.

Economists Nouriel Roubini and Stephen Miran named this phenomenon Activist Treasury Issuance in a 2024 analysis. Their findings were startling. By issuing far fewer long-term bonds, the Treasury may have succeeded in flattening the yield curve from the supply side, a modern echo of the Fed’s 1960s Operation Twist. But unlike Operation Twist, which required direct bond purchases, ATI relies purely on supply manipulation. The fewer long-term bonds that hit the market, the less upward pressure on yields. The result? Long-term borrowing costs stay lower than they otherwise might.

But the real shock lies in the magnitude of the effect. Roubini and Miran estimate that ATI shaved roughly 25 basis points off 10-year Treasury yields. That may sound small. But in terms of its stimulative impact, it’s equivalent to the Fed cutting rates by a full percentage point. This puts the Treasury and the Fed on opposing tracks. While the central bank raises rates to rein in inflation, the Treasury may be quietly easing financial conditions through its issuance choices. As Miran put it, during the tightening campaigns of 2022 and 2023, “Treasury was basically pushing in the other direction,” essentially canceling out a sizable share of the Fed’s efforts to fight inflation.

The Policy Shift Behind Treasury’s Quiet Easing

How did a subtle debt management tactic evolve into what now resembles economic stimulus? The path to Activist Treasury Issuance began during a time of chaos. In the depths of the pandemic, as the U.S. economy cratered and emergency relief poured out of Washington, the Treasury turned to short-term bills to fund the unprecedented spending surge. That approach made sense in a crisis. Bills are fast, flexible, and easy to sell. But crisis borrowing is one thing. What followed was something else.

Historically, once the dust settles, the Treasury shifts back toward long-term bonds. The goal is to lock in low rates and lengthen the maturity profile—a way to stabilize future obligations. That’s been the long-standing philosophy: stay “regular and predictable,” avoid trying to time the market. But by 2022, the landscape had changed. Inflation wasn’t transitory as the Fed had hoped, and it responded by tightening aggressively, sending interest rates to heights not seen in decades. Suddenly, issuing a 10-year bond meant locking in borrowing costs above 4%, a painful leap from the near-zero rates of the COVID era.

Rather than embrace those high long-term yields, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made a different call. She leaned hard into short-term debt. The logic? Rates might fall soon. If the Fed could wrestle inflation back down, borrowing would be cheaper later. Why pay 4% for a decade when you could roll over bills next year at, say, 3%? It was a bet. A calculated one. But still a bet.

By fiscal year 2023, nearly two-thirds of new issuance was concentrated in Treasury bills. The shift was deliberate. Analysts at the time noted that the Treasury had “shifted its issuance towards shorter-term bills,” partly to minimize exposure to persistently high long-term rates. The average maturity of the nation’s debt began to shrink, falling to around 72 months by late 2023, down from a peak of roughly 74 months just months earlier.

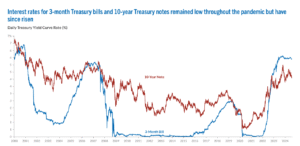

This wasn’t happening in a vacuum. The yield curve was inverted, meaning short-term rates were higher than long-term ones. In mid-2023, for instance, 3-month bills paid roughly 5.4%, while 10-year notes hovered near 4.3%. Ordinarily, a borrower would prefer the cheaper long-term rate; however, if one expects the short rate to drop, short-term borrowing can still be advantageous over time.

By mid-2023, the Treasury yield curve inverted, reflecting the Federal Reserve’s aggressive tightening while the Treasury continued to favor short-term debt issuance. Source: Peter G. Peterson Foundation

Yellen defended the heavy bill issuance as cost-effective and prudent, not an attempt to engineer a stimulus. “We never time the market… issuance should be regular and predictable,” she told skeptical senators, noting that Treasury’s debt mix remained in line with historical norms and the advice of the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee.

When asked directly whether this amounted to stealth stimulus or a pre-election “sugar high,” Yellen pushed back. “There’s nothing about issuing short-term debt that creates a sugar high for the economy,” she told lawmakers. She insisted the issuance mix followed long-standing norms and the advice of Treasury’s own borrowing advisory panel. In her view, the strategy was sound, prudent, and rooted in cost management, rather than an attempt to juice the economy.

But the line between tactical debt strategy and economic intervention may be thinner than the Treasury lets on. By pulling long-dated bonds off the table, Yellen’s team may have done more than trim borrowing costs. They may have also held down yields, dulled the Fed’s policy impact, and added fuel to a still-warm economy. And that raises a deeper question: Is the U.S. government quietly stimulating demand, even as its central bank tries to cool things down?

Operation Twist in Reverse: How Treasury Shrunk the Yield Curve Without Saying a Word

To grasp why ATI matters, it helps to look backward. In 2011 and 2012, the Federal Reserve launched Operation Twist, a maneuver designed to flatten the yield curve. The Fed sold short-term Treasuries and used the proceeds to buy longer-term ones. It wasn’t printing money, but the aim was clear: lower long-term borrowing costs to spur investment, homebuying, and growth when short-term rates were already stuck near zero.

Now rewind that play, and you get ATI. But this time, it’s not the Fed buying long bonds, it’s the Treasury choosing not to issue them. Instead of selling 10- and 30-year notes, it floods the market with short-term bills. The result? Long-term yields fall, not because demand rises, but because supply dries up. Nouriel Roubini put it plainly: “The Treasury pushed down long-term debt by selling less of it.” He and Stephen Miran call this fiscal stealth stimulus. Others have taken it further, dubbing ATI a form of “quasi QE” or “stealth quantitative easing” because of how it props up long-dated bond prices without any Fed intervention.

This shift, subtle on the surface, may have quietly buoyed the economy through a turbulent stretch. From late 2022 through 2023, even as the Federal Reserve raised interest rates above 5%, the economy stayed afloat. GDP grew a healthy 2 to 3% while unemployment barely budged. Mortgages and corporate loans remained cheaper than expected, thanks to muted long-term yields. Many economists had braced for a recession that never came. One reason? ATI was the cushion no one saw.

David Beckworth, a former Treasury economist, hinted as much. The Treasury’s issuance strategy, he argued, “helped land the plane” and prevented a hard crash. But that soft landing came at a cost. While growth stayed strong, inflation didn’t fade as quickly as hoped. Core inflation in 2023 remained stubbornly above 3%, well above the Fed’s 2% target. And here, ATI may have worked against the central bank.

By easing financial conditions when the Fed was trying to tighten them, the Treasury’s actions may have blunted the impact of higher rates while standing “in between the Fed and [the goal of] significantly bringing down…inflation,” as Miran noted. This raises a troubling prospect. Two of the most powerful economic forces in Washington may have been pulling in opposite directions, one trying to slow things down, the other quietly keeping the engine warm. And if that’s true, then the policy picture is more fractured than it appears.

The Yellen Era: ATI Emerges (2021–2024)

Janet Yellen didn’t invent short-term borrowing. But, under her leadership, it became something more—an enduring strategy rather than a temporary tool. In the early stages of her tenure, leaning on Treasury bills made sense. The pandemic had shattered demand and opened a fiscal hole that had to be filled, and fast. Bills were the emergency lever. Everyone knew it.

But by late 2022, the emergency was over. Inflation was raging, and the Fed was slamming on the brakes. Yet, the Treasury continued to tap the short end of the curve. Month after month, bills dominated issuance, far beyond what historical norms or crisis protocols might justify. Ironically, investors like Scott Bessent warned at the time that Yellen’s strategy looked less like routine debt management and more like a quiet attempt to cap long-term yields. Senators also took notice. “You’re working at cross purposes with Jay Powell…trying to give the economy a sugar high,” Senator John Kennedy scolded, encapsulating the suspicion that political motivations (goosing the economy before the 2024 election) were at play.

Miran, himself a former Treasury official, was openly critical of Yellen’s choices, even as he acknowledged that issuing bills in a crunch is “orthodox” up to a point. The orthodoxy, as Miran explained, is that if the government has a sudden financing need (say, a recession or emergency), it first issues bills, because the market can easily absorb a large volume of short-term paper, and then later terms it out into longer debt once the storm passes. What was unorthodox in this case was that the “storm” (the pandemic shock) had largely passed by 2023, yet the Treasury continued to use bills aggressively well into an economic expansion.

As ATI took shape, so too did the storm around it. What began as a quiet shift in issuance patterns soon exploded into a deeper dispute over power, priorities, and unintended consequences. Critics didn’t hold back. To them, Yellen’s Treasury wasn’t just managing debt, it was steering economic conditions in ways that looked a lot like backdoor stimulus. “Measures like ATI lead to looser financial conditions at times when monetary authorities are trying to achieve price stability…This is dangerous stuff,” Roubini wrote. If fiscal leaders start influencing yields to serve policy goals, where does that leave the Fed? What happens when investors begin to believe that long-term borrowing costs will always be massaged downward, no matter the fundamentals?

Only in the back half of 2023 did the tide begin to turn. The Treasury’s November refunding announcement included long-awaited increases in note and bond auction sizes. The share of bills dropped below one-third in fiscal 2024, a clear shift in direction. But it was a reluctant pivot. Deficits were ballooning, and the Federal Reserve was unwinding its balance sheet. Short-term debt, once a convenience, had become a vulnerability. Yellen thus found herself facing up against an unenviable task. Stretch out maturities too fast, and risk market volatility. Stay too short, and you risk a rollover or accusations of manipulation.

Continuation under Secretary Bessent (2025)

The 2024 presidential election resurrected Donald Trump’s presidency, and with it, a new Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent. A longtime critic of Janet Yellen’s short-term debt playbook, Bessent, while out of office, had warned that relying so heavily on Treasury bills was a risky distortion of fiscal discipline. Many expected that once in power, he would reverse course, but instead, Bessent has doubled down. What began as an unconventional choice under Yellen now appears to be hardening into doctrine.

By mid-2025, it became evident that Bessent’s Treasury was still avoiding increases in long-term bond issuance. In the quarterly refinancing announcement in July 2025, the department stated it “does not anticipate increasing auction sizes for notes and bonds for at least the next several quarters,” signaling that longer-term debt sales would remain steady despite rising funding needs. To fill the funding gap, the Treasury planned to raise an unprecedented $1 trillion between July and September, almost entirely through new Treasury bills. That decision marked not just a continuation of ATI, but an expansion of it in absolute terms.

Why the apparent about-face? Experts say circumstances left Bessent little choice. U.S. financing needs remained enormous: deficits have been running above $1.5–2 trillion annually, and in early 2025, the statutory debt ceiling fight had delayed issuance, resulting in a backlog of borrowing once the ceiling was lifted. Flooding the market with long-term bonds at that moment could have sent long-term yields sharply higher, undercutting the economy and risking instability. Instead, Bessent leaned on the “orthodox” tool of bills as a pressure valve.

So the Treasury reached again for the most convenient lever. “We use T-bills as a shock absorber,” a senior official explained, citing the bill market’s unique ability to soak up sudden surges in supply without crashing prices. The official framed the move as standard practice, but the scale was anything but.

Beyond just issuing bills, the Trump Treasury, under Bessent, introduced an even more activist measure: outright buybacks of long-term bonds. In a bold escalation, the Bessent Treasury announced it would double the frequency of its bond buybacks and increase the total quarterly volume to $38 billion. These “liquidity support” buybacks involve the Treasury purchasing outstanding older bonds (particularly in the 10- to 30-year range) to improve market functioning.

But they have a side effect. By taking some long-term debt out of circulation, buybacks can marginally ease upward pressure on long yields. Bessent even floated the possibility of much larger buybacks if needed. He indicated that if the Treasury market became disorderly, the department could consider increasing outright buybacks of longer-term public debt to help limit rises in long-term rates. This is essentially the Treasury contemplating a role traditionally reserved for the Federal Reserve, stepping in to cap yields in times of stress. Roubini pointedly described this as “a far deeper form of Treasury-led QE” that Bessent was now hinting at.

Most striking of all, Stephen Miran, formerly a harsh critic of ATI and now Trump’s top economic adviser, hasn’t opposed the shift. He has endorsed it. Together, the two had campaigned against Yellen’s tactics. Now they are running with them. This admission lays bare the bind policymakers are in. Once you start down the road of actively managing debt to influence rates, it’s hard to stop. Successor governments can become, in Roubini’s words, “addicted” to it or even “double down” on it. That, Roubini warned, is the danger of fiscal dependence on ATI. Once entrenched, it feeds on itself.

Economic Implications and Risks

What does Activist Treasury Issuance mean for the economy and the American people? Experts say the impact is double-edged. On the surface, ATI has provided a cushion. By keeping long-term interest rates lower than they otherwise might be, it has made credit cheaper. Families taking out mortgages, small businesses seeking equipment loans, and corporations issuing bonds have all likely benefited from this suppressed yield environment. Lower borrowing costs help sustain consumption and investment. Housing activity, job growth, and stock market valuations have all remained resilient despite the Federal Reserve’s aggressive tightening. That may sound like a win. And in the short term, it is. However, Roubini says this support comes at a cost—one that may show up not in quarterly data, but in the structural integrity of the economic system.

Inflation That Won’t Quit

The most immediate risk is inflation. If the Treasury is easing while the Fed is tightening, the combined effect may cancel out. Roubini has warned that this kind of policy contradiction encourages more borrowing, more risk-taking, and more upward pressure on prices. Core inflation remained stuck above 3% through 2024, despite one of the most aggressive Fed hiking cycles in modern history. That stubborn inflation may not be a coincidence. ATI made money easier to get, and looser financial conditions tend to fuel demand.

For American households, this means a harsh tradeoff. A slightly lower mortgage rate might be welcome, but it can be eclipsed by rising grocery bills, gas prices, and rents. Purchasing power erodes quietly and over time. ATI may have helped avoid a short-term downturn, but in doing so, it may have prolonged the inflation Americans hoped would fade.

A Dangerous Game of Short-Term Debt

There’s another hazard: the way the government is borrowing. The Treasury’s reliance on short-term bills is like taking out an adjustable-rate mortgage on the national debt. It’s cheaper upfront, but it leaves the borrower exposed. As bills mature, some in just a matter of weeks, they must be rolled over at current rates. If those rates rise, or stay elevated, the interest burden balloons.

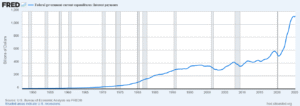

Federal interest payments have exploded to nearly $1.1 trillion by 2025, more than doubling since 2020, as short-term borrowing and elevated rates drive the fastest cost surge in modern history. Source: FRED

We’re already seeing signs of this strain. In fiscal year 2024, the federal government spent $881 billion on interest, more than double what it spent in 2020, and nearly exceeding the total amount spent on Defense programs. And if short-term rates remain high or spike further, those costs will only grow. In the worst-case scenario, if investors demand higher yields to offset rollover risk, a funding crisis could emerge. While there’s no sign of that yet, the deeper the Treasury leans into short-term financing, the more vulnerable it becomes to a shock. The Treasury starts to look less like a steward of national finance and more like a hedge fund: nimble, leveraged, and exposed to swings.

When Policy Goals Collide

Another consequence is institutional. ATI blurs the boundary between fiscal and monetary policy. Traditionally, the Fed sets the interest rate, and the Treasury takes that rate as given. ATI undermines that balance. If the Fed raises rates to slow the economy, but the Treasury eases conditions through short-term issuance, whose policy wins?

This lack of coordination could force the Fed into an uncomfortable corner. It may need to raise rates higher than otherwise necessary to counteract the Treasury’s effect. That raises the risk of overshooting and triggering a recession, not because it was unavoidable, but because policy tools were working at cross purposes. Such confusion weakens public trust and investor confidence. And it jeopardizes the central bank’s independence, which for decades has helped anchor inflation expectations and financial stability.

Roubini calls it the early stage of fiscal dominance, in which the Treasury’s needs and the political calendar begin to dictate interest rate outcomes. If the public starts to believe that rate policy is being managed for electoral or fiscal convenience, the credibility of U.S. economic leadership could erode rapidly.

Debt Strategy or Dangerous Shortcut?

Activist Treasury Issuance began as a balancing act. A tightrope walk between recession and runaway yields. A way to fund trillions without sparking panic in the bond market. Whether it bought time or merely delayed a reckoning remains unanswered. But what’s clear is that ATI has blurred the line between financing strategy and economic intervention. First under Janet Yellen, then under Scott Bessent, the U.S. Treasury has leaned into short-term borrowing not just to manage costs, but to shape outcomes. It has softened the blow of rising rates while giving the appearance of control. And for a time, it worked.

The U.S. economy, at least on the surface, has held up. Unemployment remains low while growth continues. Even as the Fed pushed interest rates to their highest levels in decades, the gears of consumption and hiring continued to turn. It’s as if policy had found a strange equilibrium with one foot on the brake, the other pressing gently on the gas. But no equilibrium lasts forever.

Economists like Roubini and Miran warn that this kind of policy tension cannot persist without consequences. Either the Fed will be forced to tighten further, risking a sudden slowdown, or the Treasury will eventually have to shift back toward long-term borrowing, exposing taxpayers to higher costs and markets to deeper volatility. At some point, the math catches up. Debts mature and bills come due. For most Americans, ATI is an invisible force. But its fingerprints are everywhere: in the mortgage rate offered by a bank, in the price of groceries, in the steady drumbeat of Treasury auctions and interest payments.

The question now is how long this uneasy balance can hold. If inflation persists or geopolitical stress jolts markets, confidence could fray quickly. And once that happens, the safe-haven illusion surrounding U.S. debt may not be as unshakable as it once seemed. As the debt pile grows and financial conditions strain, Americans would do well to recognize a hard truth: policy maneuvers may delay disruption, but they cannot eliminate risk. Markets are cyclical, after all, and no amount of monetary policy can change that. When the tools of last resort become the tools of first choice, the ground beneath can shift faster than expected.

In moments like these, when monetary restraint collides with fiscal ambition and uncertainty multiplies, diversification becomes a form of protection. Gold, a time-tested store of value in eras of monetary distortion and policy overreach, may once again serve a purpose that many had forgotten. Not as a speculation, but as insurance. Because when debt is treated as stimulus, and central bank independence blurs into fiscal necessity, it’s not just returns that investors should be thinking about. It’s resilience.