By Preserve Gold Research

The specter of banking instability is once again haunting Wall Street. Over the past several weeks, a wave of bad loans and surprise corporate failures has rattled investor confidence in the U.S. financial sector. Bank shares have swung wildly as concerns grow that credit stress could seep into broader markets.

The sudden failures of First Brands Group, a key auto parts manufacturer, and Tricolor Auto Group, a major subprime car lender, in September have only added to the anxiety. These twin collapses have shaken the foundation of Wall Street’s vast credit network, forcing several funds to rapidly unwind exposure to fragile sectors amid mounting fears that consumer and auto lending might weaken further.

Jamie Dimon, the chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, gave voice to Wall Street’s unease when he told analysts, “When you see one cockroach, there are probably more…Everyone should be forewarned.” His bank was forced to absorb a $170 million write-off following Tricolor’s collapse, a setback Dimon later described as “not our finest moment,” pledging tighter oversight in its wake.

Such candor from America’s most influential banker carries a weight that few can ignore. Nearly 20 years after the 2008 subprime crisis and just two years removed from the regional bank runs of 2023, the warning landed like an echo from the past. Once again, tremors in the supposedly insulated corners of the credit market have erupted into full view, reviving fears about what might still be festering beneath the surface of an economy many assumed was on stable ground.

As investors search nervously for the next “cockroach,” uneasy questions linger. Are these credit shocks merely isolated failures, or are they early indicators of a deeper, systemic unraveling? Could strains in auto lending and corporate debt foreshadow another cycle of financial contagion? Or might the industry’s fortified balance sheets and stricter capital rules be enough to keep the system intact?

Auto Sector Credit Shocks Stir Wall Street

Few would have expected spark plugs and windshield wipers to set off alarms on Wall Street. Car parts don’t typically keep investors up at night. But the unfolding multibillion-dollar crisis around First Brands changed that. In late September, two obscure auto-related companies, First Brands Group and Tricolor Auto Group, imploded in rapid succession, reviving an all-too-familiar anxiety: the fear of hidden leverage lurking in places investors rarely look. In finance, it’s often what investors don’t see that does the most damage. And in the case of First Brands and Tricolor, layers of risk that had long gone unnoticed suddenly burst into view.

First Brands Group, a Michigan-based auto parts conglomerate, filed for bankruptcy on September 29 after what insiders described as a “shockingly fast disintegration.” The company had amassed enormous liabilities, estimated between $10 billion and $50 billion, against a fraction of that in assets. Years of debt-fueled acquisitions and opaque off–balance sheet borrowing had left it precariously exposed. By relying on private “shadow” financing arrangements to factor receivables (essentially borrowing against unpaid customer invoices), First Brands managed to obscure a vast portion of its true debt load.

That illusion shattered when spooked creditors refused to roll over the company’s loans. What followed was a cascade of revelations. Investigators began uncovering irregularities in the firm’s financial structure, and one lending partner, Raistone, claimed that as much as $2.3 billion in funds had “simply vanished” from the supplier’s accounts. The allegation triggered a Department of Justice investigation, sending further shockwaves through the banking sector. With virtually no independent oversight and a board that had grown complacent during years of easy credit, First Brands’ implosion has raised an unsettling question across Wall Street: How could a company of this scale hide such fragility for so long?

Hot on the heels of that shock came the collapse of Tricolor Auto Group, a Texas-based chain of used-car dealerships and a subprime auto lender serving underbanked consumers. For years, Tricolor thrived on a business model built for the era of cheap credit, selling older vehicles with high-interest, in-house financing to buyers who struggled to qualify for traditional loans. During the easy-money decade, it appeared to be a winning formula.

But by early September, the company was unraveling. Mass layoffs swept through its offices as warehouse lenders abruptly pulled credit lines, alarmed by rising defaults and growing suspicions of fraud. Within weeks, Tricolor entered Chapter 7 liquidation, effectively wiping out its operations. What initially seemed like a liquidity squeeze soon turned out to be something far more troubling. Federal investigators now allege that systemic fraud ran through the company’s core operations. According to their findings, Tricolor double-pledged loans to multiple lenders and duplicated vehicle identification numbers to fabricate collateral. In plain terms, it seems the company was selling the same car and its loan more than once.

Although smaller than First Brands, with under $1 billion in securitized auto loans outstanding, Tricolor’s downfall has become a warning sign. It suggests that the pockets of excess, complacency, and misconduct that built up during years of ultra-low interest rates may now be surfacing. In the wake of Tricolor’s bankruptcy, many are questioning whether this is an isolated incident or a sign of larger issues within the auto lending industry. The practice of securitizing loans, where lenders bundle together and sell off groups of loans to investors, has become increasingly popular in recent years. However, this can lead to a lack of accountability, as lenders may not have a strong incentive to properly vet loan applicants if they know the loans will be sold off.

Hidden Risks in Private Credit Markets

The turmoil surrounding First Brands and Tricolor has cast a harsh light on the vast and often opaque network of shadow banking and private credit that supports much of corporate America’s borrowing. Since the 2008 financial crisis, a growing share of lending has migrated away from traditional banks into the hands of private equity firms, direct-lending funds, and fintech financiers. These non-bank lenders have filled the gaps left by tighter post-crisis regulations, extending credit to companies that conventional banks might avoid.

Over time, this shadow market has ballooned. Many corporations have chosen to raise funds privately rather than go public, preferring the discretion of private loans to the scrutiny of public markets. Yet that same discretion comes at a cost. Unlike regulated banks, private credit vehicles operate with minimal oversight and little obligation to disclose their true exposure. “There isn’t as much disclosure as there is in the public markets…we don’t really know what’s going on,” cautioned Ben Lourie, a professor of accounting who has studied the First Brands collapse.

In the case of First Brands, the company’s dependence on off-balance-sheet financing concealed the full extent of its liabilities until it was too late. That opacity prevented investors and regulators from recognizing the danger in time, and it has exposed how little visibility exists within parts of the private debt world. Wall Street is now wrestling with a troubling question: if an auto-parts supplier could hide billions in obligations, how many others might be doing the same? The fear of contagion has become tangible. Lourie noted, “When there isn’t as much disclosure, there’s more risk, and there’s a fear of contagion, because somebody is going to have to take on these losses, and eventually it will reach up into the banks.”

That warning no longer feels theoretical. Jefferies, a mid-sized investment bank, had been advising First Brands while simultaneously lending against its invoices through a specialist finance fund. The bank also helped place billions of dollars of those loans with other investors. Now, those investors are facing losses, and few can say with confidence where the full chain of risk truly ends. The unease running through Wall Street reflects a deeper realization that the boundary between private credit and the mainstream banking system may be far thinner than most believed.

Echoes of Past Crises

Seasoned market observers have begun drawing parallels to earlier moments when hidden leverage jolted the financial system. The collapse of Greensill Capital in 2021 and the downfall of U.K. contractor Carillion in 2018 revealed how complex financing structures such as supply-chain factoring can suddenly implode. Further back, the implosion of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998 nearly destabilized global markets, while off-balance-sheet subprime mortgage bets brought down Lehman Brothers in 2008.

The parallels aren’t perfect. Today’s stress stems less from traditional bank excesses and more from the explosive expansion of private credit since banks tightened lending after the global financial crisis. But they underline a key point. Risks can build quietly outside the traditional banking radar, only becoming obvious when a downturn or fraud exposes the fragility.

Not everyone agrees that these events signal a looming financial crisis. Some analysts argue that the failures of First Brands and Tricolor were isolated and the result of poor oversight and reckless management rather than systemic decay. Neuberger Berman’s fixed-income team described both cases as idiosyncratic “bad apples,” pointing to unique governance failures and aggressive financial tactics rather than signs of widespread instability.

Still, even they acknowledge that credit risk is on the rise after years of easy money. The volume of corporate debt and leveraged loans has ballooned, and “in a period of ready capital, it’s inevitable that greater risk will enter the system in the form of more aggressive and sometimes unscrupulous operators,” as Neuberger Berman’s chief investment officer cautioned.

With U.S. asset-backed securities outstanding swelling from an average of ~$700 billion in 2013-2020 to nearly $900 billion by August 2025, there is simply more debt (and more marginal borrowers) out there to go wrong. As the economic cycle adjusts to the lagged effects of higher interest rates, even isolated credit flare-ups put lenders on notice that vigilance is required. The domino that was First Brands might remain an outlier, or it could be the first in a line if more hidden problems emerge in the shadows of the credit market.

Fear Lingers Beneath the Market’s Uneasy Rebound

By mid-October, the aftershocks of the credit turmoil had shaken trading floors from New York to London to Tokyo. Bank stocks whipsawed as anxious investors sold first and analyzed later. “Markets have been gripped by a sense of fear and panic in the last couple of days,” noted banking analyst Timothy Coffey, as financial shares tumbled across the globe.

In the U.S., regional lenders bore the brunt. Shares of Zions Bancorp and Western Alliance plunged more than 10% in a single day after Zions reported surprise losses on two business loans and Western Alliance disclosed an alleged fraud by one of its borrowers. The timing couldn’t have been worse. Investors were already rattled by the auto loan bankruptcies and a string of smaller credit surprises. Disparate issues began to be “conflated into one big issue about credit concerns,” Coffey said. The sell-off quickly spread across the Atlantic, with European bank indices down nearly 3% and some U.K. and German bank stocks falling 5-6%, before rippling into Asian markets overnight.

Comparisons to the banking turmoil of 2023 were inevitable. Regulators in the post-SVB era had already been quizzing banks about well-known vulnerabilities: commercial real estate loans, reliance on uninsured deposits, liquidity backstops. Those conversations have not changed. But experts say the credit hiccups in 2025 are a different animal than the liquidity-driven bank runs of two years prior. “I would not equate what happened this week to the 2023 banking crisis,” asserted Fifth Third Bank CEO Tim Spence amid the market rout. He explained that the current episode was driven by specific credit events rather than systemic liquidity stress.

While a wave of strong third-quarter earnings from regional banks and reassurances from officials have helped steady the market, the episode has been a reminder of how quickly market psychology can shift. Even as prices stabilized, options traders continued to hedge against the risk of further credit troubles. As U.S. Bank Wealth Management’s Rob Haworth noted, while it was “not yet a full-blown systemic panic—it’s an increase in concern and uncertainty.”

Haworth added that “It seems like, despite some of the risks, the consumer is muddling through for now, and the market will probably eventually look through that… But we’ve got to clear some of these worry factors in the near term.” Confidence, in other words, remains delicate. The banking system’s core health may be intact, but each new jolt (a fraud here, a default there) tests the nerves of investors who haven’t forgotten how quickly financial contagion can spread when fear takes hold.

Strained Consumers, Stressed Companies

The latest tremors in banking and credit shouldn’t be separated from the deeper economic shifts that have been unfolding this year. They are emerging at a time when American households are feeling the squeeze of high inflation, high borrowing costs, and a comedown from pandemic-era stimulus.

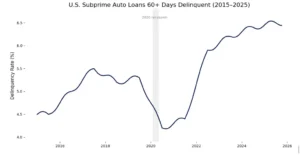

In the auto sector, cracks have been forming for some time. U.S. car repossessions surged to 1.73 million vehicles last year, the highest level since 2009 and 16% more than the year before. By January 2025, subprime borrowers were defaulting on car loans at the fastest pace in more than three decades, with 6.5% of subprime auto loans at least sixty days delinquent, according to Fitch Ratings.

Subprime auto delinquencies have climbed to their highest levels in more than a decade, reflecting growing financial strain among lower-income borrowers. Monthly trend modeled from Fitch Ratings benchmark data. Shaded period denotes the 2020 recession. Source: Fitch Ratings (Subprime Auto ABS 60+ Days)

“The consumer has been distressed for a little while… I think there’s some angst,” admitted CarMax CEO Bill Nash, whose used-car business has been hurt by rising defaults. To entice struggling borrowers into staying current, many auto lenders have been extending loan terms or offering modifications, essentially kicking the can down the road. But as many industry veterans warn, those fixes buy time but not resolution, since borrowers who struggle once tend to fall behind again.

Economists often view auto loan troubles as an early warning sign for the economy at large. “Distress in auto lending…is often seen as a bellwether to changing circumstances in the U.S. economy,” explained Professor Brett House of Columbia Business School. Lower-income Americans will do almost anything to avoid losing their cars, because without a car, they may be unable to work. “When we see stress in the auto financing market, we typically receive that as an indication that household finances are getting tighter,” House noted. In other words, more people falling behind on car payments could presage broader jumps in consumer credit problems, from credit cards to personal loans.

Tightening conditions are spreading. Credit card balances have reached record highs, defaults are creeping upward, and personal bankruptcy filings are rising as households deplete the last of their pandemic-era savings. Meanwhile, demand for big-ticket goods, from appliances to furniture, has softened. The picture forming is one of consumers stretched thin, trying to stay afloat in an economy that feels less forgiving than it did just a few years ago.

On the corporate side of the ledger, higher interest rates are likewise taking a toll. After a decade of cheap money, businesses with heavy debt loads are now facing the double whammy of pricier credit and cooling demand. Large corporate bankruptcy filings have climbed for three consecutive years, reaching levels not seen since the Great Recession. In the 12 months through mid-2025, 117 companies with over $100 million in assets filed for bankruptcy (roughly 44% above the historical average), as many cited inflation and rising interest costs among the key drivers of their distress.