By Preserve Gold Research

From a nation that once launched a revolution over a tax on tea, the United States has evolved into a government with a multi-trillion-dollar budget. This fiscal transformation didn’t happen overnight. It’s the result of over two centuries of expanding public roles and responsibilities. Despite calls for “small government,” government spending has kept rising, through war and peace, boom and bust.

Today, the forces driving that expansion are deeply entrenched. Attempts to reverse the growth have repeatedly stalled, and the trend line points only in one direction: upward. Even as policymakers talk about austerity, the public sector has become a permanent leviathan, its growth fueled by deep-seated economic, demographic, and institutional dynamics. The analysis that follows examines how government spending expanded for more than a century and why a meaningful reversal may remain beyond reach.

From Tea Taxes to Trillion-Dollar Budgets: A Brief History of U.S. Government Spending

Understanding how this happened requires looking backward. America’s fiscal history reads like a staircase built during crises. The federal government started small, funded by tariffs and a few excises. But each major war or national emergency led to a surge in expenditures and new taxes. After the danger passed, spending never fell back to its old level. It simply settled into a new plateau. Over time, those plateaus formed a steep upward climb that reshaped the federal role in American life.

In the early republic, federal power barely touched daily life. Washington relied almost entirely on import tariffs, supplemented by a few excise taxes and land sales. Tariffs often accounted for up to 90% of revenue, reflecting how limited the government truly was. There was no income tax. During this period, federal expenditures stayed modest, typically around only 1-3% of the young nation’s GDP

The government did spend more during wartime, such as the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War (1846-1848), but shrank shortly after. In 1835, the Treasury even paid off the national debt. The minimalist fiscal state of the founding era, funded unobtrusively by tariffs on foreign goods, was a far cry from today’s expansive budget.

The Civil War and the First Income Tax (1861 to 1872)

The Civil War shattered the old limits. Lincoln’s administration scaled spending to levels the country had never seen, building vast armies and financing unprecedented operations. To fund it, the government imposed the first federal income tax in 1862 and printed new paper currency. These steps marked a sharp break from the long reliance on tariffs.

After the war, lawmakers repealed the income tax, and spending fell. Yet it never returned to antebellum lows. Debt obligations, veterans’ benefits, and new administrative capacities kept the government larger than before. Americans learned that in a true crisis, federal power could expand rapidly, and once expanded, it rarely returned to its earlier size.

The Progressive Era and the Revival of the Income Tax (1890s to 1913)

By the turn of the 20th century, economic and social changes were stirring calls for a stronger federal role. The economy was industrializing, and problems like corporate monopolies, impure foods, and financial panics seemed beyond the power of small state governments alone. Agencies like the Interstate Commerce Commission and early food safety regulators emerged. They were small, but they established a new expectation that Washington should police national markets.

The decisive shift came with the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913, which permanently authorized an income tax. Within a few years, Congress sharply raised top rates, especially during World War I. What had been a government of limited means now had the keys to a financial engine that could scale with the economy itself. By 1930, income taxes (both individual and corporate) accounted for about 60% of federal receipts, eclipsing tariffs.

World Wars and the Permanent Leviathan (1917-1945)

World War I (1917-1918) was the first great test of the new income tax and of America’s willingness to support massive federal spending. Spending climbed to more than 30% of GDP as the country armed itself and financed allies. Although the 1920s brought some restraint, the government never returned to pre-war levels. The taste of large-scale mobilization was too tempting, and the tax system that supported it stayed in place.

Then came the Great Depression of the 1930s, followed by World War II – a one-two punch that transformed the scope of the federal government. New Deal programs created Social Security, job initiatives, welfare support, and financial oversight while spending grew in an attempt to revive the economy. Then the war arrived and pushed expenditures to levels that exceeded half of GDP. Payroll withholding made income taxes routine for millions, broadening the federal reach deep into household finances.

After 1945, spending declined only slightly. The Cold War demanded a permanent military establishment, and New Deal programs became untouchable pillars of American life. Postwar America entered a new fiscal reality in which yearly outlays rarely fell below 20% of GDP. The limited government of the nineteenth century had vanished.

The Great Society, the Cold War, and the Rise of Mandatory Spending (1960s to 1990s)

The next major wave of expansion came with the Great Society programs of the 1960s and the escalating Cold War. Medicare and Medicaid reshaped federal obligations, while Social Security continued to grow. At the same time, the Vietnam War lifted defense demands. These forces pushed spending higher once again.

A defining feature of this era was the advent of “mandatory spending,” i.e., expenditures that are on autopilot, dictated by eligibility rules rather than annual budget votes. Their costs rose automatically as the population aged and healthcare prices climbed. By the 1980s, these programs, along with interest payments, consumed the majority of federal dollars. Defense eventually declined as a share of the budget after the Cold War, but mandatory spending filled the vacuum. By the 1990s, the government had locked itself into obligations that politicians could barely touch without igniting public backlash.

The 21st Century: Endless Crises and Structural Peaks (2001 to Today)

The 21st century so far has only reinforced the pattern: new crises keep ratcheting spending to fresh heights. The attacks of September 11 expanded homeland security and pushed defense budgets upward. The Great Recession was followed by massive stimulus, bailouts, and welfare expansions. Spending dipped afterward, but not to pre-crisis levels.

Then the pandemic arrived. Congress moved trillions in relief through the system at extraordinary speed. The government signaled that in any national emergency, it might intervene at virtually unlimited scale. Even after the crisis eased, spending remained far above the norms of earlier decades.

The result has been a series of one-way growth spurts. Almost every decade has brought some new peak, whether driven by war, recession, or national policy ambitions. The reality is that America’s public sector now touches every facet of life, from retirement income to healthcare, education, science research, transportation, and beyond. And the forces that built this giant show no sign of reversing.

The Rise of “Invisible Taxation”: How Americans Were Quietly Taxed Over Time

While federal spending was on the rise, another quieter revolution was occurring: the spread of taxation at every level of government. Across the country, governments discovered that new revenue streams could be introduced slowly, framed as temporary, and then absorbed into daily life. These taxes operated in the background. They appeared in paychecks, at the register, in property assessments, or on utility bills. Because the burden spread across many small touchpoints, public resistance stayed muted. Americans adapted bit by bit, and governments learned how to draw more from the economy without sparking open revolt.

State Income Taxes (1910s-1960s)

For more than a century, states avoided income taxation. That changed in 1911, when Wisconsin adopted a modern income tax and opened the door for others to follow suit. During the Great Depression, more states copied the model, often describing their measures as temporary or targeted at the wealthy. By the late 1930s, seventeen states had enacted income taxes, and few ever reversed course. Today, more than forty states tax personal income. Because each adoption felt incremental, the public rarely saw the larger pattern forming, yet the result was clear. A new layer of taxation settled onto the same paycheck already taxed by Washington.

Sales Taxes (1930s)

Sales taxes also began as emergency tools. Mississippi introduced the first broad sales tax in 1930, when Depression-era budgets collapsed. Other states followed quickly. By the end of the decade, more than twenty had adopted similar taxes. Although promoted as temporary fixes, these levies proved too lucrative to abandon. Today, nearly every state taxes retail purchases. Shoppers barely notice the small add-on at the register, but those pennies compound into billions. States discovered that small rate increases could pass quietly, allowing spending to rise without sparking a coordinated backlash.

Property Taxes

Property taxes have existed since colonial times, yet their impact often feels hidden. When home values rise, tax bills rise with them even if rates don’t change. Many homeowners pay through escrow, which dulls the shock of year-to-year increases. During housing booms, local governments collect windfall revenue without lifting a finger. When values fall, they rarely cut spending to match. Instead, they adjust assessments or introduce supplemental levies. Over time, this dynamic produces a steady upward drift that fuels rising local budgets for schools, policing, and infrastructure. The burden becomes part of the cost of home ownership itself.

Payroll Taxes

Payroll taxes started small. Social Security contributions began in 1935 at a modest rate shared by workers and employers. Medicare payroll taxes arrived later in the 1960s. As both programs expanded, Congress repeatedly raised the rates. Today, the combined payroll rate reaches 15.3% for most wages, and many workers pay more in payroll taxes than in federal income taxes. Because deductions happen automatically and support popular programs, they rarely provoke the same anger as income tax hikes. This quiet acceptance allowed payroll taxes to become one of the largest funding sources in the federal system and a major driver of entitlement growth.

Fees, Fines, Surcharges, and “Non-Tax Taxes”

Alongside formal taxes, governments have increasingly leaned on fees, user charges, and fines, often referred to as “hidden taxes”. These include vehicle registrations, license renewals, tolls, utility surcharges, building permits, and an ever-widening menu of mandatory payments. Individually, the amounts seem trivial, but collectively, they’ve grown into significant sources of government revenue.

Politicians favor fees because they can argue these charges are optional or tied to services used, and thus not tax increases. But when essential activities like driving require paying fees, they function like taxes on the public. Increases in fees and fines often come with little to no public debate or oversight, making them an easy way for governments to raise revenue without facing voter pushback.

The Expansion Trap: Why Government Spending Rarely Shrinks

If history is any guide, periods of government contraction are rare. There are strong, built-in forces that favor the growth of public spending and equally strong barriers against reducing it. Politicians find that while expanding government programs is easy (and popular), scaling them back is extraordinarily difficult. This asymmetry creates a kind of one-way ratchet that tightens with each cycle.

Bureaucratic Incentives Favor Growth

Within every government agency or department, there is a natural incentive to seek more funding, not less. Bureaucracies, like organisms, strive to expand their turf, staff, and influence. A larger budget means an agency can do more, raising its importance. Leaders push Congress for resources by pointing to unmet needs, while no one gains a reward for shrinking their own office. As a result, efforts to trim programs usually meet stiff internal resistance. Temporary crisis agencies often seek new missions to remain in place. This bias creates a self-reinforcing cycle in which growth strengthens political clout, and that clout shields future growth. As the old quip puts it, a government bureau might be the closest thing to eternal life we see on earth. In practice, few agencies ask to shrink, and most drift steadily toward higher cost and broader scope.

Baseline Budgeting Ensures Permanent Increases

Budget rules themselves also push spending upward. Washington relies on “baseline budgeting,” which treats last year’s outlays as the floor and assumes increases from there. If an agency received one hundred million dollars, the following year’s baseline might rise to one hundred three million dollars. Anything below that number gets labeled a cut, even if the agency still receives the same dollars as before. This illusion makes genuine reductions politically dangerous.

Lawmakers often claim to trim spending, yet they usually slow the rate of growth rather than reduce totals. Projections from the Congressional Budget Office assume programs rise with inflation unless Congress acts, so the default is always more. Temporary projects also slip into future baselines and stay there. Over time, the ratchet moves in one direction, and the budget rarely retreats.

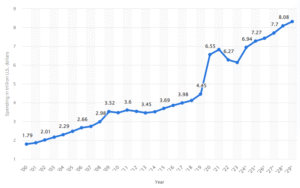

Total outlays of the U.S. government in fiscal years 2000 to 2029 (in trillion U.S. dollars)

Every major shock in the past two decades pushed federal spending to a new peak. Even after stability returned, the floor remained higher, hinting that the federal budget may now be shaped more by accumulated obligations than by deliberate restraint. Source: Statista

Crisis-Driven Ratchets

Virtually every emergency, whether war, recession, natural disaster, or pandemic, leads to a surge in government spending. While that’s understandable and often necessary, most emergency spending never entirely disappears when the crisis passes.

World War II ended rationing and price controls, yet it left behind a permanent military-industrial complex and a vast system of veteran benefits. The Great Depression created programs like Social Security, the SEC, and the FDIC, all of which became structural pillars. The 2008 crisis raised support for unemployment insurance and food assistance, and those baselines stayed elevated. The pandemic is likely to leave a similar legacy: emergency measures such as expanded child tax credits and higher Medicaid rolls may be trimmed, but not fully reversed.

Economist Milton Friedman once warned, “Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.” Agencies created for a crisis seek new missions. Funding boosts meant to be extraordinary get folded into ordinary budgets. Each crisis lifts the floor of government spending, and that floor rarely comes back down.

Public Demand for Benefits vs. Political Reward for Promises

Public expectations create another barrier to shrinking government. Voters claim to oppose high taxes and waste, yet they rely on the benefits major programs provide. They punish officials who threaten those benefits. Politicians understand this instinct. Expanding a program brings thanks, while cutting one risks backlash from a focused and angry constituency.

Polls show this contradiction clearly. Most Americans support reducing spending in theory, but when asked which programs to cut, almost nothing wins approval except foreign aid, which represents a tiny share of the budget. Most major programs, from Medicare to veterans’ benefits, draw far more support for increases than reductions. This leaves elected officials boxed in. A proposal to trim something like Medicare would inevitably invite attack ads and jeopardize a reelection bid.

For lawmakers, it’s far safer to maintain or raise funding, even if it requires borrowing or optimistic projections. Thus, democracy itself tends to favor additive policy (new programs, expanded eligibility) rather than subtraction. Once a benefit takes root, it gains a sense of entitlement, and removing it becomes politically perilous.

Mandatory vs. Discretionary Spending Lock-In

A growing share of federal spending now runs on autopilot. Mandatory programs such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, farm supports, and interest payments must be funded under existing law. Congress doesn’t vote on them each year, and changing their formulas is politically difficult. That means two-thirds of spending is on autopilot, growing or shrinking as dictated by external factors such as the number of eligible beneficiaries or the cost of medical care.

Meanwhile, the discretionary side of the budget, which covers areas like defense, education, and transportation, has steadily shrunk as a share of total spending. Even deep cuts wouldn’t resolve long-term pressure, since the fundamental drivers are entitlements and interest costs. Lawmakers usually avoid confronting these programs and instead trim around the edges, often slowing growth rather than reversing it.

Why Government Spending Is Not Going Away (and Will Likely Grow Faster)

Looking ahead, the forces pointing to further spending growth are, if anything, intensifying. Despite the newly created Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) ‘s well-intentioned efforts to eliminate waste, government spending continues to rise. DOGE’s ~$215 billion in estimated savings this year pales in comparison to the ~$7 trillion annual federal budget. And the idea of returning to a small government posture looks increasingly unrealistic given the pressures now building across demographics, debt, security, technology, and public expectations.

Demographics: An Aging Nation Means Rising Entitlements

The American population is getting older. As the Baby Boom generation moves fully into retirement, the number of seniors receiving Social Security and Medicare benefits will continue to swell. The senior population will roughly double from 2000 to 2030, and these programs will expand automatically as beneficiary numbers increase. Social Security and Medicare already consume close to 10% of GDP and are projected to take even more. Cutting benefits remains politically toxic, since retirees vote at high rates and view these programs as earned. Meanwhile, the worker-to-beneficiary ratio keeps falling, which means fewer workers support more retirees. Absent a politically improbable overhaul, these programs will drive federal spending higher almost irrespective of anything else.

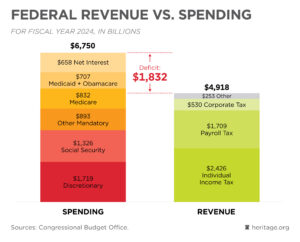

Even in a strong economy, Washington’s 2024 ledger reveals a deficit of nearly two trillion dollars. The bulk of spending is on programs that expand automatically, suggesting that future budgets may strain the nation’s financial capacity long before voters or policymakers demand change. Source: CBO

Rising Debt and Escalating Interest Costs

Federal debt now exceeds $38 trillion, and interest payments are among the fastest-growing line items in the budget. When rates were near zero, the burden seemed manageable. Now, with higher rates and larger debt, interest costs are exploding. In recent years, the government has spent more on interest than on most major agencies, and projections show these outlays could reach well over a trillion dollars within the decade. Interest can’t be cut, so rising debt pushes future spending higher whether lawmakers want it or not. This creates a cycle in which past deficits fuel tomorrow’s budget growth, even if every other program were frozen.

Global Security Pressures

Although defense spending as a share of GDP is lower today than during the mid-20th century, it’s poised to remain high or grow amid renewed global tensions. The U.S. faces a new era of power competition, notably with a rising China and a resurgent, aggressive Russia. Even many deficit hawks in Congress exempt defense from cuts, citing national security concerns. Meanwhile, threats like international terrorism haven’t disappeared, meaning homeland security and counterterrorism funding remain priorities. The public tends to support high defense spending when international threats are salient, despite concerns about the budget deficit. This environment places a floor under national security spending, with veterans’ benefits and global commitments adding further weight.

Infrastructure, Green Energy, AI, and Technological Arms Races

Government spending isn’t driven solely by responding to problems; it’s also about investing in the future. Recent laws have authorized trillions for infrastructure, clean energy, semiconductor manufacturing, climate initiatives, and emerging technologies. And while they’re often framed as one-time investments, history shows that once created, these programs tend to create ongoing obligations. Looking ahead, the AI arms race could spur huge public expenditures as well. Governments around the world are pouring resources into AI research and applications (for defense, healthcare, etc.) to avoid falling behind, and the U.S. has already allocated billions for AI R&D.

Voter Expectations for Safety Nets

Lastly, the social expectation in America has shifted such that, in times of crisis or personal hardship, people look to the government for help. The Great Recession and the pandemic reinforced the idea that Washington will backstop the economy when trouble strikes. In 2020, the government sent out multiple rounds of stimulus checks to most households, enhanced jobless benefits, and even paused student loan payments. While those were emergency measures that were broadly popular at the time, they have set powerful precedents.

Apart from crises, roughly a third of Americans rely directly on major assistance or insurance programs, and many more depend on indirect support through housing, healthcare, or education. Entire industries (healthcare, defense, education) are now entwined with federal funding. This creates constituencies who will fight tooth and nail against cutbacks. A middle-class suburban family might not see itself as dependent on “big government.” Yet, it enjoys mortgage-interest tax breaks, public schooling for its kids, perhaps Medicaid for an aging parent’s nursing home, and expects federal relief if a hurricane hits its town.

Reversing any existing program would invite the question: what will people do without it? And often, no private or charitable alternative is readily available at scale, so the status quo is maintained. Over time, these accumulated expectations form a ratchet as real as any fiscal rule: Americans expect a robust government safety net, and woe to the leader who tries to remove it.

The Result: A Government That Grows in One Direction

The outcome is a government that expands far more easily than it contracts. Growth happens almost by default, while retrenchment tends to appear only when the country faces acute economic or political stress. In practice, this has meant that every political ideology, once in power, presides over a larger budget. Progressives tend to add new social programs, while conservatives favor defense or tax cuts that widen deficits. Both paths lift spending. Under Reagan, defense and entitlements surged; under Obama, stimulus and healthcare did the same. Even leaders who vowed to shrink government found they couldn’t, as the political cost of austerity outweighed the reward.

Experts say reversing this trajectory would require structural reforms and political courage on a scale that currently seems implausible. It would mean telling the American people that programs they rely on must be curtailed or that taxes must be raised sharply to pay for them—messages that no successful politician in recent memory has delivered. Instead, the incentives all push toward maintaining and growing the status quo.

In a sense, the U.S. has made a grand bargain with itself: high spending in exchange for a certain level of national security, economic stability, and social welfare. The affordability of that bargain can be debated, but the commitment to it has been unshakable. The American government’s size today is the product of its people’s will (expressed through politics) over generations. And that collective will, consciously or not, has chosen a larger government footprint. Voters want benefits without sacrifice, and politicians oblige. But resources are finite, and unlimited growth can’t last forever. The old warning that there is no free lunch could prove to be more than a cliché in the not-too-distant future.