By Preserve Gold Research

For decades, the United States has benefited from a rare asymmetry. It’s been able to run chronic fiscal deficits, expand its balance sheet, and repeatedly flirt with political dysfunction while continuing to attract vast amounts of foreign capital at comparatively low cost.

That privilege rested on several pillars. The dollar’s reserve status and the depth of U.S. capital markets allowed Washington to finance large debt loads that would strain most other sovereigns. Layered on top was confidence in American institutions. For years, global investors treated U.S. assets as the default destination in moments of stress. When uncertainty rose elsewhere, capital flowed toward the U.S. almost automatically.

But that reflex is now weakening.

What is unfolding doesn’t look like panic or capital flight. Foreign investors are not abandoning U.S. markets en masse. Instead, long-term investors are quietly reassessing how much risk they want to carry. And they are doing it early, before headlines force their hand. When investors known for moving slowly start adjusting ahead of events, it’s usually not a short-term trade. More often, it reflects deeper questions about trust and durability.

The implication is uncomfortable. If capital that once absorbed U.S. imbalances with little hesitation is now seeking additional compensation, the concern may not be volatility alone. It may be trust itself.

What the Treasury Market Is Signaling Beneath the Surface

The U.S. Treasury market is often discussed as a single entity, but its investor base is highly segmented. Short-term bills, intermediate notes, and long-dated bonds serve distinct purposes, particularly for foreign official institutions.

Historically, long-duration Treasuries were a feature rather than a flaw for reserve managers and pension funds. They allowed institutions to deploy capital at scale, limit reinvestment risk, and signal confidence in U.S. fiscal stability. Duration, in effect, embodied trust.

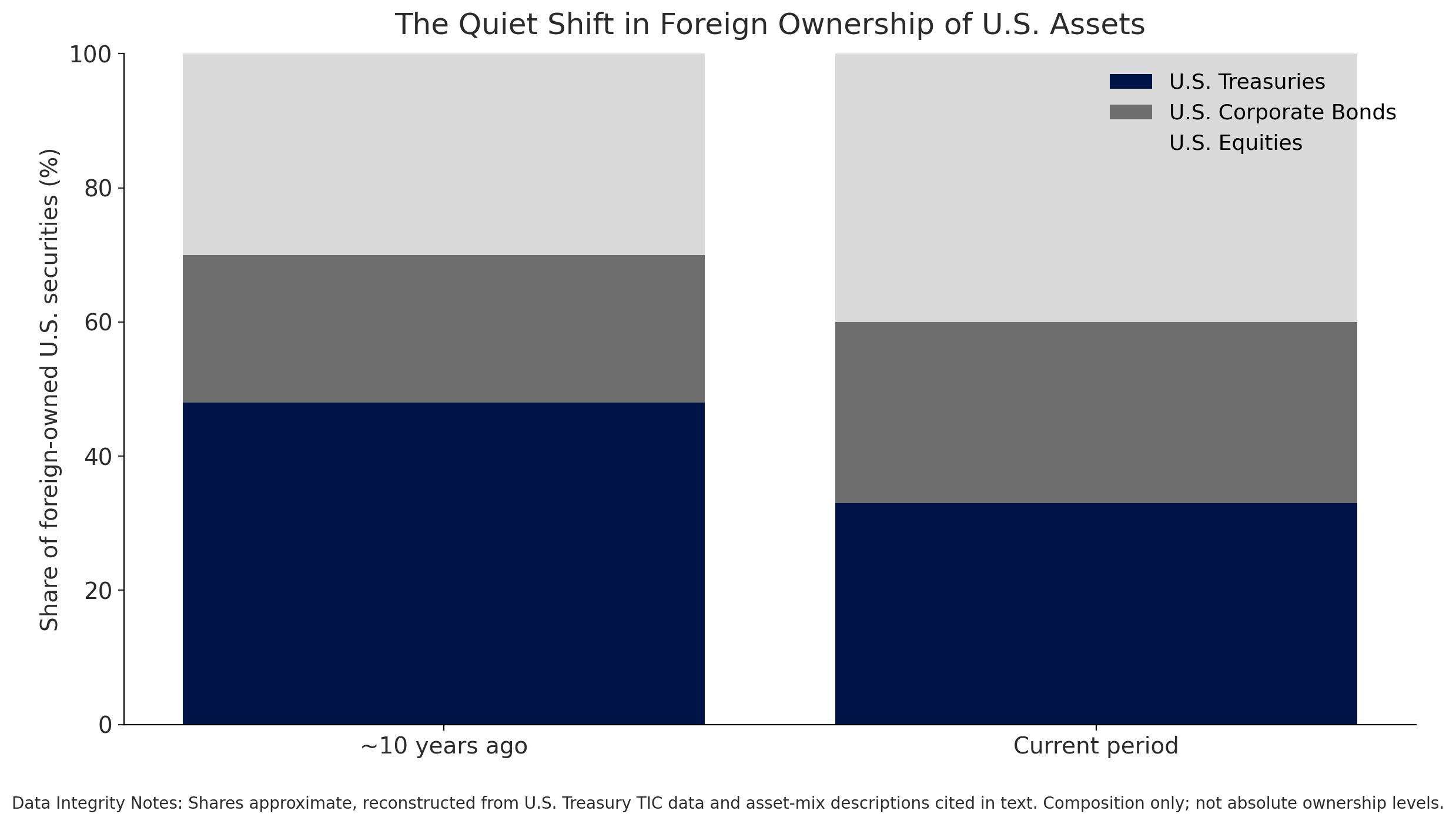

That relationship has begun to change at the margin. Treasury data show that roughly 21% of U.S. securities remain foreign-owned. Within that share, about one-third is held in Treasuries, down from nearly half a decade ago. Around 27% is allocated to corporate bonds, with the remainder concentrated in U.S. equities. The overall exposure still reflects confidence in American markets, but the composition has shifted in ways that matter over time.

The clearest confirmation has come from long-term allocators. In early 2026, several large European pension funds, among the most conservative investors globally, publicly acknowledged changes in their posture. Two major Nordic funds disclosed that they had sold most or all of their U.S. Treasury holdings, citing rising risk rather than yield considerations.

One Swedish pension executive described the decision as driven by “decreased predictability of U.S. policy in combination with large budget deficits and a growing national debt.” A Danish fund echoed the assessment, characterizing its divestment as rooted in weak U.S. public finances. These decisions were not tied to a specific crisis. As one Nordic investment manager observed, funds are now “fundamentally assessing” whether U.S. exposure still fits long-term mandates, even in calm markets.

That distinction matters. Reassessment in periods of relative stability tends to reflect structural concern, not reactive fear. Markets are rarely alarmed by politics; they adapt to it. Over time, persistent political noise wears down the dollar’s premium, leading investors to demand higher yields to offset governance risk. The adjustment is incremental, but it compounds.

Policy Uncertainty and the Erosion of Predictability

Uncertainty remains the bane of markets, and over the past year, there’s been no shortage of it. Much of the unease traces back to Washington. In rapid succession, investors have faced unexpected tariff announcements, proposals to tax foreign capital, renewed debt-ceiling brinkmanship, and a steady stream of fiscal surprises. Each episode has weakened assumptions that once anchored long-term positioning.

One episode proved especially revealing. The “Liberation Day” tariffs announced in April 2025 caught global investors off guard, particularly those positioned for continued trade openness. Rather than exiting U.S. assets outright, many Asian insurers and pension funds layered currency hedges onto their existing exposure. Markets reacted in an unusual way. The dollar weakened even as U.S. bond yields rose.

That divergence was telling. Analysis at the time noted that the combination of unilateral tariff escalation and discussion of new taxes on foreign holders undermined the implicit premium attached to U.S. assets. Confidence, not yield differentials, began to drive pricing behavior.

Credit rating agencies reinforced that signal. What once seemed unthinkable became reality when Fitch removed the U.S. from the top credit tier in mid-2023. Moody’s followed by cutting its rating to AA+ in May 2025, citing political gridlock and fiscal slippage. None of the three major agencies anticipates outright default, but the direction matters. Their assessments suggest U.S. policy credibility may no longer be taken for granted. Many investors now read this shift as the emergence of a higher “fiscal risk premium”, an added margin that may be required to hold U.S. debt as confidence becomes less automatic.

Market behavior has, at times, echoed those concerns. In late 2025, bond market volatility began to resemble patterns more commonly associated with emerging market stress. U.S. Treasuries declined alongside equities, blurring their long-standing role as a stabilizing asset. So far, no outright capital strike has emerged. U.S. debt auctions have continued to clear, and equity markets remain near record highs. But Washington’s uncertainty appears to be forcing a revaluation of the U.S.’s role as global anchor. If sustained, that shift raises uncomfortable questions about how the country will manage its own debt load.

Why Today’s Repricing Looks Structural, Not Cyclical

Markets are accustomed to cyclical swings. Inflation rises, rates follow. Growth slows, policy eases. Capital flows reverse and eventually return. These movements are familiar and, over time, mean-reverting. Structural repricing is different. It occurs when the assumptions used to value an asset class begin to shift, not because of a single shock, but because the framework that once made risk legible no longer feels stable.

Foreign capital is especially sensitive to this distinction. Domestic investors can rationalize drawdowns as temporary or politically manageable. But external holders, by contrast, must assess not only returns but governance, currency integrity, and long-run policy coherence.

Views differ on whether the change is a short-lived technical blip or something deeper. Some strategists argue that flow-driven dislocations can be sharp yet reversible, questioning whether hedging activity will fade and traditional relationships reassert themselves. Others note that many foreign institutions were already underweight U.S. bonds and that diversification, if it continues, is likely to be gradual. From this perspective, Treasuries remain a safe haven for medium-term investors.

The broader backdrop, however, points toward rising structural demand for alternatives. The United States now carries debt near 100% of GDP while relying on a shrinking share of foreign buyers to absorb issuance. The long-standing gap between domestic savings and investment is no longer closed effortlessly by global capital. For long-horizon investors, persistent deficits raise questions about durability rather than direction. From that vantage point, diversification looks less like speculation and more like insurance.

Large institutions are already behaving accordingly. Sovereign wealth funds still allocate heavily to the U.S., but increasingly structure that exposure with greater hedging and internal rotation. These patterns are typically associated with structural realignment, not short-term noise.

There are limits to how far repricing may go. The credibility of the Federal Reserve and the depth of U.S. markets remain powerful anchors. Relative value still matters. As yields in Europe and Japan have risen, the hedged premium on U.S. Treasuries has narrowed. If overseas yields fall or U.S. policy stability improves, some pressure could reverse. Over time, however, trust is the variable that matters most. Technical factors dominate in the short run, but structural confidence sets prices in the long run.

The Dollar’s “Exorbitant Privilege” Is Becoming Conditional

For much of the postwar era, the United States has benefited from what policymakers once described as an “exorbitant privilege.” The dollar’s role as the world’s primary reserve and settlement currency allowed the U.S. to finance itself on uniquely favorable terms, even as deficits widened and debt accumulated. Trust in the dollar was not only widespread but also structural.

That privilege rested on a dense web of mechanics. A large share of global trade has long been invoiced in dollars, even when neither party is American. Commodities are priced in dollars. International banks rely on dollar funding markets to intermediate global credit. U.S. Treasuries function as the dominant form of high-quality collateral in financial plumbing, used to secure derivatives, repo transactions, and cross-border liquidity. Offshore dollar markets, from London to Asia, extend the dollar’s reach far beyond U.S. borders.

Together, these channels created a powerful feedback loop. Foreign institutions needed dollars to transact, hedge, and settle. To obtain them, they accumulated dollar assets, especially Treasuries. That persistent demand suppressed U.S. borrowing costs, allowing Washington to issue debt at scale without the same constraints that other sovereigns face. The privilege was not simply that the dollar was dominant, but that demand for dollar assets was relatively price-insensitive.

That insensitivity is changing.

In past cycles, rising U.S. deficits were often met with steady foreign buying, particularly at the long end of the Treasury curve. Today, foreign demand remains substantial, but it’s more selective. While the dollar isn’t likely to be displaced anytime soon, losing reserve elasticity comes at a cost. As policy coherence frays and fiscal discipline becomes harder to rely on, demand for U.S. assets grows more conditional. The dollar’s privilege, once treated as an entitlement, increasingly looks like a performance review. The United States can still borrow in its own currency and supply the world with safe assets, but it does so under closer scrutiny. Trust hasn’t disappeared, but it’s no longer automatic.

The Search for Policy-Neutral Assets

Against this backdrop, global investors are not retreating so much as repositioning. The most durable reallocations are occurring in assets that sit outside direct U.S. policy jurisdiction; instruments that don’t rely on fiscal restraint or institutional continuity to preserve value.

The clearest signal comes from central banks themselves.

In both 2024 and 2025, official sector gold purchases reached levels that stand out even by historical standards. Central banks collectively bought more than 1,000 metric tons of gold in 2024, marking the third consecutive year above that threshold and placing total accumulation near the highest sustained pace on record. Preliminary data for 2025 suggest the pace remained elevated throughout the year, with purchases heavily concentrated among emerging-market reserve managers but increasingly visible among developed-market institutions as well.

What makes this behavior notable isn’t the scale alone, but the context. These purchases continued as gold prices reached new nominal highs and as U.S. Treasury yields offered the most attractive income in years. In other words, central banks aren’t chasing returns, but rather insulation. They were prioritizing an asset whose defining feature is independence.

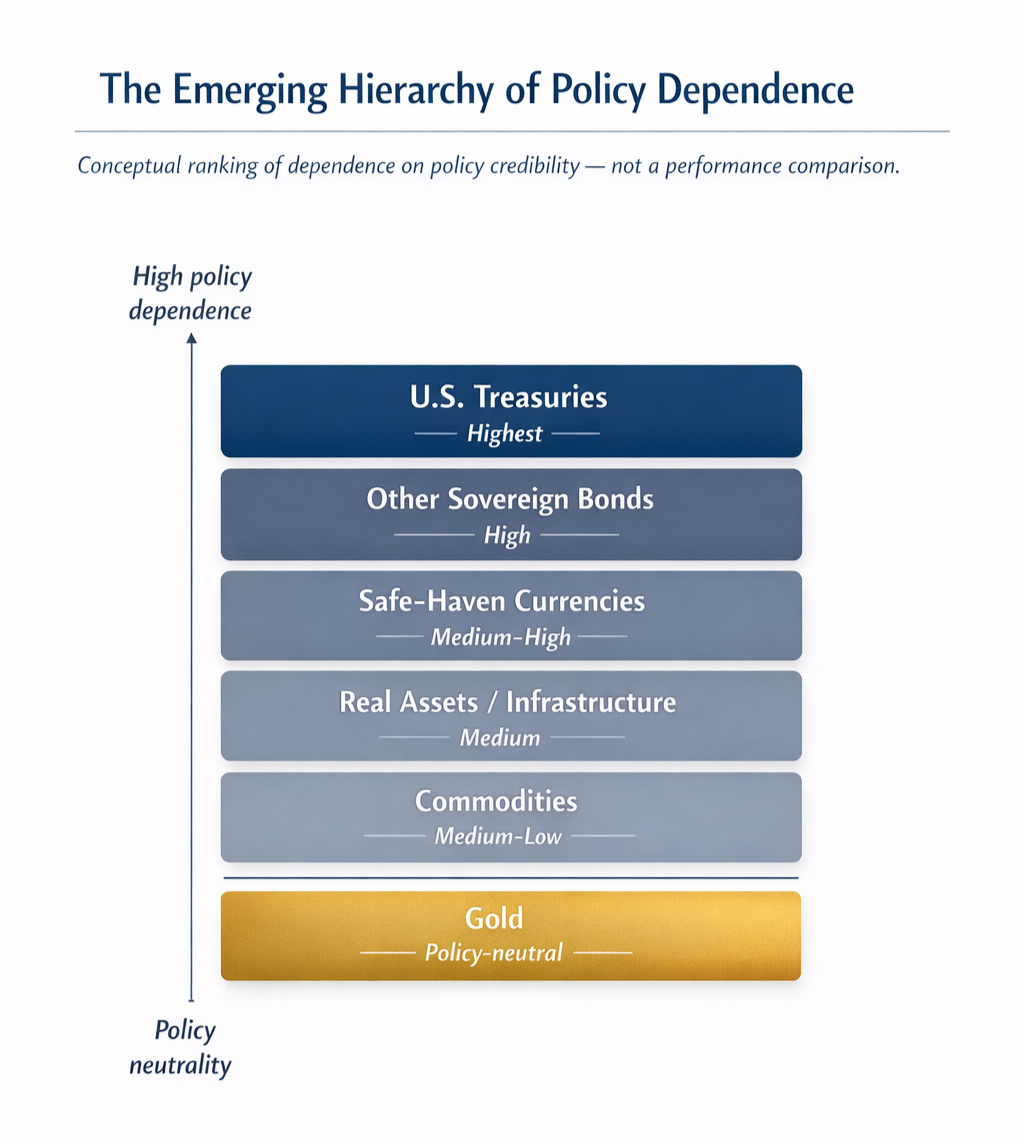

Gold doesn’t depend on another government’s balance sheet. It carries no credit risk, no rollover risk, and no exposure to future policy reinterpretation. It’s liquid across borders and immune to the political conditions that increasingly shape financial markets. For reserve managers tasked with preserving purchasing power across decades, those characteristics matter more than short-term performance.

Other diversification channels exist, but they tend to share limitations. Traditional safe-haven currencies such as the Swiss franc and Japanese yen have attracted renewed interest, but they remain embedded within national policy frameworks and monetary discretion. Real assets and infrastructure offer inflation-linked returns, but often come with liquidity constraints, regulatory exposure, or their own geopolitical entanglements. Commodities provide diversification, but their volatility ties them closely to global growth cycles.

By contrast, gold occupies a narrow but increasingly relevant category: policy-neutral capital. It’s not designed to outperform. It’s intended to persist. Advances in portfolio construction have made it easier for institutions to incorporate this kind of exposure without abandoning yield elsewhere. Gold no longer needs to replace other assets to justify its role. It only needs to offset concentrations of policy risk. The point is not that alternatives are free of downside. They’re not. But risk is no longer being evaluated purely in terms of price movement or income generation.

Implications for the U.S. Economy

For Americans, the upshot of foreign repricing is that borrowing costs could rise. U.S. Treasury yields form the baseline for mortgages, corporate loans, and municipal bonds. If foreign investors pause or demand extra yield, that raises rates across the board.

Estimates suggest that a 1 percentage-point drop in China’s dollar reserves could add ~20 basis points to long-term U.S. yields. That alone would add tens of billions to annual interest payments on the debt. Currently, the U.S. Treasury is offering new 10-year notes around 4-4.5%. If overseas demand wanes enough to push that to, say, 5%, mortgage rates (usually 2-3% above the 10-year) could rise by half a point or more, materially increasing monthly costs for homeowners.

Higher yields would also tighten corporate finances. Companies that borrowed heavily during the ultra-low-rate era may face steeper debt costs on refinancings. Even municipal projects and student loans could feel the pinch. From a federal budget perspective, higher yields add a debt-service burden. Interest outlays would grow faster than projected, potentially crowding out other spending or requiring tax hikes. This can create a loop in which rising deficits push yields higher, which in turn worsens deficits.

Currency and inflation effects could follow. A sustained drop in dollar demand tends to weaken the dollar, making imports more expensive and exporting U.S. inflation. Over time, a weaker currency could feed into higher consumer prices, complicating the Fed’s job of controlling inflation.

On the positive side, Americans enjoy some advantages. The U.S. remains a deep, diversified economy with a highly innovative private sector, structures that have historically attracted long-term capital. But that’s a delicate balance. Policymakers can’t simply inflate their way out, because higher interest rates and a weaker dollar could still hurt growth and ordinary consumers. The era of “free money” from abroad appears to be ending, meaning Americans will have to earn favorable financing conditions through transparent governance.

What the Slow Repricing of U.S. Risk Signals Ahead

A slow repricing of U.S. risk is already underway. The United States remains deeply investable, and its markets continue to anchor global capital, but the terms under which that capital is provided are shifting. What was once absorbed almost reflexively is now scrutinized more closely. For many long-term investors, diversification away from assets tied tightly to policy assumptions has become less a statement and more a matter of prudence.

Even as near-term economic data remain firm, markets are placing greater weight on policy credibility than in past cycles. Trust, rather than earnings or inflation alone, is being repriced. When foreign holders reassess that confidence, the adjustment tends to be incremental: a higher required return here, shorter duration there, or a modest reallocation at the margins.

As trust becomes conditional, portfolios concentrated in policy-dependent assets may warrant gradual recalibration. History suggests that periods of elevated fiscal uncertainty often favor assets whose value doesn’t rest on any single government’s balance sheet or policy path—time-tested stores of value that have endured across cycles precisely because they stand apart from them.