By Preserve Gold Research

A growing chorus of economists is warning of a looming recession, with some experts putting the odds of an economic downturn at over 90%. After a brief stretch of seemingly durable growth, new data releases have re-stoked fears that a recession could be forming. Slowing job creation, softening confidence, and policy uncertainties have converged to create a potent mix, and the big question now is whether policymakers have the tools to respond in time.

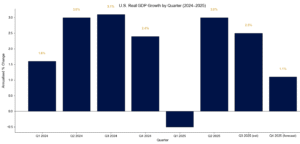

Risks began intensifying in early August 2025, after a weak employment report. The economy produced an average of only 35,000 jobs per month over the three months ending in July, a sharp drop from roughly 128,000 during the prior quarter. Hiring has cooled to its slowest pace since 2020, raising red flags across a range of industries from manufacturing to government. The same week, new data showed that economic growth in the first half of 2025 averaged an anemic 1.2% (annualized), a steep drop from the 2.8% growth rate achieved just a year earlier. Remove growth from data centers and information-processing technology, and the economy would have grown just 0.1%, according to Harvard economists.

This combination of tepid job gains and cooling output has prompted many to question whether the long-anticipated downturn is finally materializing. “The likelihood of a recession went up because of these job numbers,” warned Harry Holzer, an economist at Georgetown University. Political drama has only added to the economic jitters. The government shutdown has trudged on for 30 days and counting, making it the second-longest shutdown in US history.

While many government workers have been furloughed or forced to work without pay, the ripple effects are also being felt in the private sector. Small businesses that rely on government contracts are facing financial strain, and consumer confidence has taken a hit amid uncertainty about the future. “We’re gradually reaching a point where the shutdown becomes something more significant,” warned Gregory Daco, chief economist at EY. If the shutdown continues, a “vicious cycle” could ensue, with furloughed workers cutting back on spending, leading to further economic slowdown.

Analysts Sound the Alarm

To many seasoned observers, the recent slowdown in hiring and output is reminiscent of past recessions. “The risks are increasingly high that we’re going into recession,” warned Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, after reviewing a recent jobs report. “We’re not there yet and maybe this thing gets turned around…but that’s increasingly becoming hard to do with each passing week.”

Zandi isn’t alone in his assessment. Across the field, forecasters have begun highlighting a range of red indicators that echo the pre-recession patterns of the past. A job market at a “virtual standstill,” as Zandi described it, has seen the unemployment rate rise while job growth has slowed to a crawl. In Zandi’s view, a negative monthly employment change would be the definitive alarm bell: “As soon as you see payroll employment decline in a month, that’s when alarm bells should start going off,” he said in September. At the moment, payrolls are still growing, but the margin is razor-thin.

After a solid run through 2024, the U.S. economy stumbled at the start of 2025 before regaining momentum in the second quarter. Growth is expected to moderate again heading into year-end as policy and credit headwinds return. Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Atlanta Fed GDPNow Model, October 2025

At the same time, manufacturing has weakened, and industrial production is softening. Interest-sensitive sectors like housing have begun to buckle as the lagged effect of higher mortgage rates continues to drag them down. On their own, these datapoints might be survivable. But together, they’re squeezing an overleveraged economy at the worst possible moment.

Recession forecasting is an infamously tricky art, and even the most astute observers admit to humility. They “tend to be unforecastable,” notes Claudia Sahm, a former Federal Reserve economist known for the “Sahm rule” recession indicator. “Often there’s an event that causes people to lose confidence, change behavior, and start a downward spiral.” But simply limping along is no cause for celebration. “A slow-growing economy is not a good economy,” Sahm says.

New data from UBS has only deepened the unease. In an assessment of hard economic indicators from May through July, the bank concluded that recession risk now stands at 93% based on readings of income, production, consumption, and employment. UBS described the economy as “soggy”, warning that conditions have deteriorated to levels that historically align with major turning points. While the bank’s analysis stopped short of formally predicting a recession, it emphasized that the nation appears to be stuck in a slow-growth environment that could easily slip into something worse.

It’s this scenario that unnerves analysts. The danger isn’t just a slowdown. It’s the possibility of a long stretch of stagnation that could leave households feeling trapped. Sahm and others have argued that avoiding a technical recession isn’t enough, insisting that a weak economy with little growth remains a failing outcome for American workers. For many families, the difference between a shallow recession and years of stagnation is academic. They will feel the impact either way. Both can drain savings, sap confidence, and leave people wondering whether the promise of economic security is fading.

Warning Signs Across the States

Regional fractures are beginning to appear beneath the national data, and the state-by-state picture suggests an economy on far shakier footing than the top-line numbers imply. Moody’s Analytics reports that 22 states, along with Washington, D.C., are either in recession or at elevated risk based on a composite of economic indicators. Nearly one-third of the country by geography, representing roughly one-third of US output, now sits in vulnerable territory.

These weak spots span the map, from manufacturing regions in the Midwest to stressed pockets in the South and West, signaling that the strain is neither isolated nor easily contained. Another third of states are merely “treading water” with little or no meaningful growth, while only a shrinking minority continues to expand, and even that momentum is fading. Viewed from above, the national economy looks steady, but zoom in, and the landscape gets spotty.

California and New York stand at the center of this story. As the largest and third-largest state economies, experts say their trajectories will determine whether the country avoids a downturn or enters one. At the moment, both states appear to be treading water, neither contracting nor convincingly strengthening. Yet their influence is enormous. California’s tech engine and New York’s financial sector drive investment, hiring, and confidence far beyond their borders. If either begins to weaken, the repercussions could spread quickly through supply chains, capital flows, and labor markets. “Whether the national economy suffers a downturn appears to rest on the big California and New York economies,” stressed Zandi.

Other economists have offered similar cautions. Scott Anderson, chief economist at BMO Capital Markets, recently likened California and New York to “canaries in the coal mine” for the US economy. “I do think we’re on shaky ground here,” Anderson told MarketWatch, referring to those states’ struggles. The same sectors that fueled the post-pandemic rebound are now contending with higher borrowing costs, tighter financial conditions, and more cautious hiring. If tech and finance falter at the same time, the rest of the nation could feel the hit.

There is still room for optimism, though the margin is narrowing. California retains powerful engines of innovation, particularly in artificial intelligence, entertainment, and clean energy, any of which could help offset regional drags. New York, for its part, could benefit from resilient tourism, steady service-sector spending, and a rebound in financial activity if conditions stabilize. But as Zandi notes, his recession-risk methodology uses a holistic set of indicators, closer to the National Bureau of Economic Research approach—employment, income, production, sales, etc. By those measures, some state economies are much weaker than their GDP alone suggests.

Policy Crosswinds Are Pulling the Economy in Opposite Directions

Why has the economy become so unpredictable? Zandi describes the current situation as a set of “crosswinds” buffeting the economy. On the one hand, there are headwinds such as eroding business confidence, trade tensions, and persistent inflation. On the other hand, there are still some tailwinds from technological investment. Experts say the balance between the two will determine whether the country slides into recession or narrowly avoids one.

Headwinds: Policy Friction Is Dragging on Confidence and Capital

Trade conflicts and restrictive immigration measures have become heavy anchors on growth throughout the year. Economists caution that tariffs are like a hidden tax, spreading through supply chains, inflating prices, and reducing efficiency. Meanwhile, tighter immigration limits have thinned the labor pool, making it harder for employers to fill essential roles and constraining potential output. These de-globalization pressures have been building for years, and experts say the latest escalation could deepen and prolong their drag on the economy.

Compounding the strain, new surveys show a sharp deterioration in supply chain confidence across North America. Manufacturing firms report growing pessimism about both supply stability and the investment climate, with metal producers, capital goods manufacturers, and automotive companies hit hardest by the trade environment. A Q3 report by Dun & Bradstreet concluded, “This severe downturn could be particularly indicative of the impact of ongoing U.S. tariff policies and trade disputes directly affecting North American production and sourcing.”

The findings suggest that businesses are increasingly prioritizing resilience over cost efficiency, diverting resources toward contingency planning and alternative sourcing rather than expansion. This shift, while prudent, carries its own risks. A focus on risk avoidance may restrain innovation and slow capital formation just when investment is most needed. The report also noted that “despite many major central banks lowering interest rates so far this year, a significant increase in uncertainty for global trade, supply chains, and geopolitics has dominated business capital expenditure decisions.”

Confidence has suffered accordingly. The same survey found that sentiment toward new investment fell by more than 16% in the US during the third quarter, outpacing the global decline. Firms are increasingly unsure whether they can secure the funding needed to sustain operations, let alone expand them.

Inflation and high interest rates have added another layer of complexity. Although price pressures have eased from their earlier peaks, inflation remains a whole percentage point above the Federal Reserve’s target. The Fed’s tightening campaign, which began in 2022, cooled price growth, but at a steep cost. Credit has tightened across nearly every sector, and the flow of capital that once fueled expansion has thinned. Housing has been among the hardest hit, as mortgage rates above 7% crushed affordability and sidelined buyers. Even as rates have inched lower, recovery has been slow, constrained by cautious lenders and wary consumers.

Tailwinds: Technology Has Kept the Economy Afloat, For Now

Artificial intelligence and technology-driven expansion remain among the few genuine tailwinds in an otherwise lackluster economy. The boom in AI investment has become a powerful force, lifting stock prices and sparking a new wave of corporate spending. Companies have poured capital into automation and digital infrastructure in the hope that new efficiencies might offset rising costs elsewhere. Investors, too, have been drawn to the promise of innovation, driving valuations higher and creating a sense of momentum that stands in contrast to the broader slowdown.

Yet this strength raises an uncomfortable question: is an economy propped up by a handful of technology giants a good thing for the rest of the country? The surge in AI may be cushioning the downturn for now, but its benefits are uneven, concentrated in specific regions and industries. If the next phase of growth depends so heavily on a narrow slice of the market, what does that mean for the majority of workers and businesses left behind? Any minor setback, be it a pullback in consumer spending, a chip shortage, or a supply chain disruption, could chop the only remaining leg supporting the economy.

As Ludovic Subran, Chief Economist at Allianz, points out, “The gap between the Magnificent Seven and the rest of the industry leaves markets vulnerable to any slowdown in their spending, or shortfall in their earnings. A sharp slowdown in capital expenditure, should it occur, could ripple across both tech and adjacent sectors – trimming earnings projections and testing current multiples.” History offers parallels. While the “MAGA” stocks may seem unstoppable now, it’s worth remembering that in 1999-2000, Microsoft and Cisco both faced similar challenges. The giants of yesterday are not always the giants of tomorrow.

The ‘Low-Hire, Low-Fire Economy’ Is Starting to Show Cracks

Few things are as pivotal to avoiding a recession as the labor market. Jobs are the lifeblood of consumer spending, and consumer spending drives the bulk of the economy. In this sense, the labor picture has been paradoxical. Hiring has slowed sharply, even as unemployment has remained relatively low. It’s been a “low-hire, low-fire” environment, noted Fed Chair Jerome Powell in September. In other words, employers are hesitant to expand payrolls but remain unwilling to cut staff.

Many companies are waiting for clarity, pausing recruitment in hopes that conditions will stabilize. That restraint has helped keep joblessness contained, but it has made the job search more difficult, particularly for new entrants to the labor force. For months, low layoffs have acted as a firewall protecting the economy from outright recession. But that firewall is beginning to crack.

Layoffs have started to rise across major industries, signaling a shift in employer confidence. Amazon announced plans to cut roughly 14,000 corporate positions this month, part of a broader restructuring that could ultimately affect as many as 30,000 workers in its US operations. UPS has already eliminated close to 48,000 jobs as part of a large-scale cost-reduction effort. GM, facing weakening demand for electric vehicles, has begun cutting US roles, with around 1,200 jobs permanently eliminated at its Detroit EV plant and another 550 affected at battery-cell facilities in Ohio. What once appeared to be isolated adjustments now look like the early stages of a more systemic pullback.

The effects are already showing at the margins. Temporary staffing firms report reduced demand for contract workers, often a harbinger of broader cuts. Initial jobless claims have begun to edge higher in several states. And wage growth, while still positive, appears to be losing momentum. Experts say that once layoffs gain visibility, fear spreads. Hiring freezes multiply, spending slows, and an ordinary slowdown can evolve into a deeper slump.

The coming holiday season could prove decisive. Retailers typically ramp up seasonal hiring late in the year, a test of both consumer appetite and business confidence. If that surge falls flat, it may signal that companies are preparing for tougher months ahead. As sentiment weakens, those expectations can become self-fulfilling, tightening the feedback loop between fear and retrenchment. What was once a resilient labor market may soon become its own source of fragility.

A Crisis of Confidence Could Turn Fear Into a Self-Fulfilling Recession

A few potential wildcards loom in late 2025, but arguably the largest is the overhang of the ongoing federal government shutdown. Since Congress failed to fund the government beginning October 1, over 900,000 federal employees have been furloughed, and another 2 million have been working without pay. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the shutdown could shave between $7 billion and $14 billion off real GDP in the fourth quarter, amounting to a 1 to 2 percentage-point hit.

Services that families and businesses depend on are beginning to falter. Federal aid programs for low-income Americans are facing delays or temporary suspensions, air traffic controllers are working without pay as flight disruptions mount, and federal contractors are facing uncertainty. The longer the shutdown continues, the higher the chance that these ripples become waves.

What makes this shutdown particularly concerning is its timing. The labor market is showing strain, growth has slowed, and confidence feels brittle. When people begin to believe that instability will worsen, they behave differently. Spending slows and investment plans are often postponed as economic uncertainty rises—something that monetary policy alone might be unable to reverse. A downturn that was never inevitable can suddenly take shape because people begin to expect it.

If lawmakers reach a resolution soon, the damage could be contained and some of the disruption reversed. But if the impasse drags into the holiday season, the risk of a recession deepens. Even without a formal recession, the strain is already visible. Families are coping with higher living costs. Businesses are contending with rising expenses and persistent uncertainty. Each is tightening its belt in small, cautious ways that, taken together, can slow the broader economy.

Public sentiment reflects that unease. Opinion polls show a pessimism reminiscent of the years after the 2008 financial crisis. In a recent Wall Street Journal/NORC survey, nearly 70% of Americans said they feel the “American Dream” is fading or was never real to begin with—the bleakest reading in the poll’s 15-year history.

For most Americans, the label of “recession” matters less than the realities they live with. The real struggle is keeping a job, paying the bills, and keeping a business alive. Many are preparing for the worst even as they hope for relief. As Mark Blyth, a professor at Brown University, noted, “Nobody knows” what will happen next, and anyone claiming certainty is likely fooling themselves. The prudent path, say advisors, is caution. If a recession arrives, preparation will soften the blow. If it doesn’t, little is lost by being vigilant. After the past few years, from pandemic collapse to rapid recovery and the relentless surge of inflation, Americans have learned one enduring lesson: the unexpected has a way of returning. The question is not whether another shock will come, but how ready we will be when it does.