By Preserve Gold Research

Something deep in the world’s economic bedrock is shifting, and it could have major implications for America’s place at the center of global commerce as central banks prepare. In the shadow of looming conflict and an ever-growing mountain of U.S. debt, countries around the world are racing to reclaim their gold from U.S. vaults. Confidence that once seemed ironclad is cracking at the seams as central banks look to hedge their bets. Plane by plane, pallet by pallet, gold bars are leaving New York and Fort Knox and heading to vaults overseas. Each shipment of gold out of the country signals a quiet verdict: foreign countries are losing faith in the United States. And it’s not just gold that they’re worried about.

Nations Repatriate Gold as Trust Erodes

For decades, the world’s central banks saw the United States as the safest place to store gold. U.S. vaults, such as the famed Federal Reserve vault in New York, safeguard thousands of tons of foreign gold, a symbol of trust in America’s financial stewardship. But that trust is no longer implicit. From Europe to Asia, countries are increasingly demanding their gold be brought back home.

Consider Germany, which holds the world’s second-largest gold reserves after the U.S. At the end of World War II, Germany entrusted much of its gold to U.S. storage, confident in American stability. Fast forward to early 2025, and roughly 1,236 metric tons, only about one-third of Germany’s 3,352-ton cache, still rests beneath Manhattan. That pile, worth more than €100 billion, glints in the dark while doubts grow in daylight.

German officials are now openly voicing concern about keeping any of the country’s remaining gold reserves abroad, with some calling for repatriation. Marco Wanderwitz, a lawmaker from Germany’s CDU party, has renewed calls to inspect and verify the gold held in New York. Markus Ferber, a member of the European Parliament, went further, demanding that “official representatives of the Bundesbank must personally count the bars and document their results” in the U.S. vault. This is no longer fringe paranoia. It’s a mainstream request from one of America’s closest allies and a sign of how far confidence in Washington has fallen. Even the European Taxpayers’ Association has warned that Germany should haul its bullion home at once, arguing that when debts soar and power shifts, immediate access could prove decisive.

Germany is far from alone. In recent years, a host of large and small countries have quietly repatriated gold from foreign storage or launched plans to do so. Poland pulled home 100 tons of gold from the Bank of England in 2019, with Poland’s central bank chief saying that gold “symbolizes the strength of the country.” Hungary and Romania also brought significant portions of their gold reserves back to domestic vaults around that time. In 2015, even Australia, another U.S. ally, announced efforts to bring half its gold home from abroad. The Netherlands and Belgium have similarly moved to reclaim gold stored abroad over the past decade. More recently, in 2022 and 2023, central banks in emerging powers accelerated their gold stockpiling and repatriation efforts. For instance, the Reserve Bank of India reportedly hauled home 100 tons of gold last year.

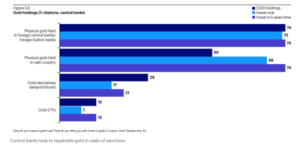

Central banks are trading paper claims for hard metal, aiming to hold nearly ¾ of their reserves in physical bullion at home within five years, while interest in swaps, futures, and ETFs steadily fades. Source: Mining.com

Although every move may stem from distinct motives, they all converge on a single, unsettling conclusion. The long-held confidence in the U.S.-led financial order (and the dollar) is splintering. Geopolitical flashpoints, economic instability, and the threat of sanctions are prompting countries to seek what they deem the only reliable hedge: physical bullion kept under their exclusive control. Paper promises and digital ledgers are no longer enough. Sovereign treasurers want weighty bars they can count, stored in vaults they control.

Weaponization of the Dollar Undermines Trust

A major catalyst for this global gold repatriation wave has been the weaponization of the U.S. dollar in international disputes. Over decades, the U.S. dollar became the world’s reserve currency, and countries accumulated trillions in dollar assets (like Treasury bonds) and kept reserves (including gold) under the guardianship of institutions like the New York Fed. This system relies on trust. Trust that the U.S. will always act as a neutral, responsible steward. But recent events have cracked that trust.

The turning point was arguably Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the subsequent Western response. In an unprecedented move, the United States and its allies froze about half of Russia’s $640 billion in foreign reserves, effectively cutting off Russia’s access to its own money. To many nations, this was a wake-up call. If it could happen to Russia, could it happen to us? Suddenly, what was once theoretical became very real. Overseas reserves could be seized or frozen if one falls afoul of the U.S.-led financial order.

In the aftermath, central banks worldwide began reevaluating their reserve strategies. According to a 2023 survey by the World Gold Council, 68% of central banks now plan to retain their gold reserves domestically, a significant increase from 50% in 2020. In other words, most central bankers worldwide no longer feel comfortable storing gold in foreign centers like New York or London—a sea change in attitude in just a few years. As one Invesco analyst put it, the new central bank mantra is, “If it’s my gold, I want it in my country.”

The U.S. has increasingly used the dollar-based financial system as a geopolitical bludgeon, imposing sanctions, cutting off banking access (SWIFT), and leveraging its currency’s dominance to pursue foreign policy goals. While these actions may be justified from the U.S. perspective, the unintended consequence has been a loss of confidence among other nations. Longtime U.S. partners observe that what started as a tool for adversaries could eventually be used more broadly. This perception gained further traction when U.S. officials and lawmakers began openly discussing punitive measures that seemed extreme by historical standards. For example, seizing foreign-held assets or even weaponizing U.S. debt as a form of leverage.

This shift is part of a broader “de-dollarization” trend among nations wary of Washington’s financial reach. Central banks are diversifying their reserves away from the dollar, increasing holdings of alternative currencies and commodities. But gold has emerged as the favored hedge. In 2022, central banks worldwide bought a record 1,136 metric tons of gold, the largest annual surge in gold buying in modern history. The colossal gold buying continued in 2023 and 2024, as central banks collectively amassed 1,037 and 1,045 tons of gold, respectively.

Within the United States, calls for transparency regarding its own gold reserves have also grown louder. In June 2025, Representative Thomas Massie introduced the Gold Reserve Transparency Act of 2025, a bill that would audit the U.S. gold reserves in Fort Knox and other vaults for the first time in decades. “Americans deserve transparency and accountability from the institutions that underpin our currency,” Massie said, emphasizing that the public has a right to know that the gold is indeed there. Even President Trump has expressed support for verifying America’s gold, remarking, “We’re going to Fort Knox… to make sure the gold is there.” What message does it send globally when trust has frayed so much that America’s own custodians are questioning the contents of the cupboards?

A Debt-Fueled Time Bomb

Compounding the loss of confidence from geopolitical frictions is a massive internal problem of America’s own making. As of mid-2025, U.S. federal debt stood at nearly $37 trillion, roughly equivalent to 122% of America’s entire annual GDP. This debt mountain has been accumulating for years, but its pace has accelerated with the rollout of large spending programs over the past half-decade.

In May 2025, the credit rating agency Moody’s downgraded the U.S. government’s last coveted “Aaa” debt rating, a rating it had held since 1919. “Successive US administrations and Congress have failed to agree on measures to reverse the trend of large annual fiscal deficits and growing interest costs,” Moody’s analysts wrote bluntly. They noted that U.S. interest payments are now significantly higher than those of any similarly rated country.

The numbers are startling. The U.S. is running annual budget deficits of around $2 trillion, even in “peacetime” and prosperity. And each year, trillions more are added to the debt. Every new dollar borrowed must find a willing lender, historically, foreign governments or investors. But what if those lenders lose interest? Moody’s downgrade came with an ominous note that such fiscal trajectory “could trigger a bond market rout“ if investors demand higher yields or balk at buying U.S. Treasuries. The mere announcement of the downgrade sent Treasury bond yields higher, a sign that investors required a higher return to compensate for the perceived higher risk. Bond vigilantes, long dormant, may be awakening.

“It basically adds to the evidence that the United States has too much debt,” warned Darrell Duffie, a Stanford finance professor and former board member of Moody’s. “Congress is just going to have to discipline itself, either get more revenues or spend less.” Duffie’s stark admonition underscores that the patience of both domestic and foreign creditors is wearing thin. If Washington cannot get its fiscal house in order, investors will eventually force the issue by dumping bonds or refusing to buy except at exorbitant interest rates. In plain terms, the U.S. government could find itself paying punishing rates just to roll over its debt, compounding the burden and squeezing the budget in a vicious cycle.

Once the largest foreign holder of Treasury bonds, China has steadily reduced its holdings to around $0.9 trillion, the lowest in over a decade. Other nations like Japan (the largest holder) have also been cautious, especially as the dollar’s future comes into question. Ray Dalio, famed investor and founder of Bridgewater Associates, noted a “severe imbalance between supply and demand“ in the U.S. bond market—too much new debt and too few willing buyers. Dalio observed that foreign investors like China and Japan “are pulling back,” meaning the U.S. Treasury might soon struggle to sell its debt unless yields rise significantly. Unsurprisingly, this is beginning to play out today. By late 2024 and into 2025, yields on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds rose to levels not seen in over 15 years as the market struggled with persistent inflation and a surge in new bond issuance.

Why does this matter? Because if the U.S. cannot finance its spending at reasonable rates, it faces dire choices. One option is for the Federal Reserve to step in and print money to buy the debt, essentially monetizing it. But this is a recipe for currency devaluation. Inflation has already been a worry in recent years, and it could skyrocket if the world loses faith in U.S. financial discipline.

Even without overt money-printing, the sheer supply of Treasuries flooding the market is exerting upward pressure on interest rates and downward pressure on the dollar. The U.S. dollar index (measuring the greenback against other major currencies) has wobbled as more countries strike trade deals in alternative currencies and as investors weigh the long-term outlook. A weaker dollar may help U.S. exports, but it also means imported goods become more expensive, another conduit for inflation to reach U.S. consumers. It’s a dangerous tightrope. Too much debt, and either the currency weakens, rates rise, or both. Each path carries pain.

This is why the gold moves by foreign central banks are so pertinent. It signals that major players are hedging against the decline of the dollar. Gold is effectively a bet against the dollar, suggesting that today’s paper wealth may not retain its value tomorrow. The fact that even U.S. lawmakers are pushing for gold audits and U.S. states are removing taxes on gold (11 states have reaffirmed gold and silver as legal tender) reveals an underlying concern that the dollar’s supremacy is not guaranteed. When trust in a currency falters, people return to what history has shown to have real value.

War Clouds and Inflation Fears

As if the financial strains weren’t enough, the world is also edging closer to serious geopolitical conflict. In what many see as a prelude to a wider conflagration, Israel launched strikes against Iran in mid-2025, targeting Iran’s nuclear facilities and military assets. The immediate economic fallout was felt in oil markets, with crude oil prices jumping to levels not seen in over a decade within just hours of the attack. Americans at the gas pump have yet to see the worst of it, but analysts warn that if the conflict is prolonged, energy prices could surge further. War in oil-producing regions often leads to supply shocks and panic buying. For instance, during the 1970s oil embargo, energy-driven inflation rocked the U.S. economy. A new Middle East war raises the specter of a similar scenario in the 2020s.

But it’s not just the Middle East. War tensions are also simmering in Eastern Europe and East Asia. The Russia-Ukraine war, ongoing since 2022, continues to strain global commodity supplies and geopolitical alliances. And in Asia, China’s ambitions over Taiwan keep military planners awake at night. If a conflict in the Taiwan Strait breaks out, the economic shockwaves—disrupting trade and semiconductor supplies and potentially prompting severe sanctions—could make Americans’ current troubles seem mild.

How does this relate to gold and the dollar? In periods of extreme uncertainty and fear, especially war, investors and nations alike flock to safe havens. And the two classic safe havens are gold and U.S. Treasury bonds. But here’s the rub: if the conflict involves or implicates the United States (either directly or via major allies), the usual safe harbor of U.S. Treasuries might not seem so secure. By contrast, gold has no political allegiance and no counterparty risk. It is, as some call it, “crisis currency.”

For example, during the 2023 conflict between Hamas and Israel, gold prices surged to record highs. Analysts cited the war, along with a weakening U.S. dollar and expectations of looser Fed policy, as reasons for gold’s leap. With a potentially larger war involving Iran (and, by extension, possibly great powers), the appeal of gold has become even more pronounced.

War also often leads to explosive government spending on defense, aid, and economic support, among other things. The U.S. has been no exception; proxy conflicts and military buildups have already stretched its budget. A hot war could force open the fiscal floodgates further at a time when the national debt has already reached nosebleed levels. “Smart money” knows this and prices it in. Suppose markets suspect, for instance, that the U.S. is about to embark on another multi-trillion-dollar military campaign (or emergency stimulus to counteract war-induced recession). In that case, they may preemptively sell dollars and buy hard assets. It becomes a self-reinforcing cycle—war fears weaken the dollar’s appeal, which strengthens gold’s appeal.

Gold’s Resurgence and the Looming Reset

Taken together, these trends point to a potential paradigm shift in the global financial order. The unipolar era of unquestioned American economic dominance, with the dollar as king and U.S. institutions as the world’s trust agents, faces its stiffest challenge in living memory. Some are even calling it a “full-blown global reset,” as faith in fiat currencies wavers and gold re-emerges as the anchor of stability.

It’s as if we are rewinding the clock to an earlier time, where gold, not the U.S. Treasury or Federal Reserve, is the final guarantor of value. Fiat money is failing to convince the growing number of skeptics who point to endless money printing and fiscal recklessness. Every repatriation of gold, every new central bank purchase, every bilateral trade deal that skirts the dollar, every crypto experiment, and every call to audit Fort Knox are signals of dissatisfaction with the status quo and a groping for alternatives.

Some experts suggest that we may be approaching what historians will refer to as the next great monetary reset. The first was the move off the gold standard during World War I, and the second was the end of Bretton Woods in 1971 when the dollar’s gold convertibility was nixed. Now, with debt spiraling and trust evaporating, we could be nearing another juncture. What might that look like? Possibly a world where multiple currencies share power, where gold backs some national monies again or sits as a neutral reserve between them, or even a world where digital currencies issued by major central banks compete for dominance. But in any scenario, gold is being positioned as a cornerstone and a hedge against an uncertain future.

For ordinary Americans, the gold bars moving from New York to Frankfurt may not seem like a big deal. However, if foreign nations buy fewer U.S. bonds, it can result in higher mortgage rates and increased interest on car loans and credit cards. If the dollar gradually loses its purchasing power, it means the prices of imported goods, from electronics to clothing to food, could rise. If inflation kicks up further, it could mean retirement nest eggs shrink to a fraction of their former size. In a worst-case scenario of a financial crisis, jobs and livelihoods could be at risk as the economy adjusts to higher interest rates and a weaker dollar.

Monetary Realpolitik Enters a New Era

With nations pulling their gold from U.S. vaults and preparing for a time when U.S. guarantees might not hold, the writing is on the wall. Geopolitical standoffs, swelling deficits, and threats of new sanctions are prompting central bankers to exchange paper claims for gold bars they can physically weigh. And while the gold buying trend has been dominated by emerging market countries like China and Turkey in recent years, a similar unease has recently spread through Main Street and Wall Street. In 2023, the U.S. Mint recorded its busiest year on record as Americans rushed to buy gold and silver coins, sensing that uncertainty could strike without warning. Nations are fortifying their war chests, and households might consider doing the same. As history has shown, hesitation can come with a heavy price tag if the system creaks all at once.