By Preserve Gold Research

The American dream of homeownership has slipped beyond reach for millions as housing prices continue to rise. After years of rock-bottom interest rates and a pandemic-era home buying frenzy, buyers now face a one-two punch: record-high home prices and surging mortgage rates. Housing affordability has reached its worst level in decades—nearly 75% of U.S. households cannot afford the median-priced new home in 2025. How did we get here? A large part of the answer lies in the Federal Reserve’s extraordinary interventions in the economy. Through ultra-low interest rates and trillions of dollars in bond purchases, the Fed helped fuel a historic run-up in housing costs. Experts predict that this trend could continue in the coming years, pushing even more households out of the market while creating greater wealth inequality.

Ultra-Low Interest Rates, Sky-High Home Prices

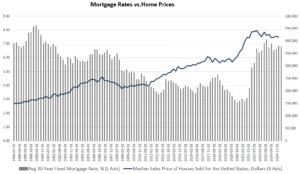

For much of the past 15 years, the Federal Reserve kept interest rates at historic lows, ostensibly to stimulate economic growth. But an unintended side effect was soaring home prices. The relationship is intuitive: when mortgage rates fall, borrowers can afford larger loans, allowing sellers to demand higher prices. Homebuyers focus on the monthly payment; at a 3% interest rate, a $300,000 mortgage carries a roughly $1,700 monthly payment, whereas at 6%, that same loan costs nearly $2,300 a month. Cheaper credit expands the pool of eligible buyers at a given price point, bidding up housing prices across the board. Real estate agents are well aware of this dynamic. It’s why they cheer for lower rates, which bring out more buyers and inflate home values (and their commissions).

U.S. mortgage rates (gray bars, left axis) versus median home prices (blue line, right axis) over recent decades. Notice how falling interest rates have coincided with surging home values, demonstrating the inverse relationship between borrowing costs and housing prices. Source: Mises Institute

Beyond simple affordability math, there is a monetary twist: the Fed typically lowers rates by injecting new money into the financial system. As economist Robert Murphy explains, “When the central bank wants to cut rates, it buys more assets and floods the market with more base money… [Falling interest rates] are a manifestation of monetary inflation, and monetary inflation often shows up as asset price inflation.” In other words, the same easy-money policies that lower mortgage rates also increase demand for assets like housing, driving prices even higher. This was seen in the years after the 2008 financial crisis and again during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, when the Fed slashed rates to near zero. From 2009 to 2021, mortgage rates plummeted to levels not seen in generations and, not coincidentally, U.S. home prices doubled in many markets. By 2022, home prices nationwide were 40% higher than they had been just five years earlier, contributing to the highest inflation in 40 years. Cheap credit had effectively supercharged housing demand, turning homes into hot commodities and outpacing any gains in income.

However, what goes down must eventually go up. By 2022, inflation had spiked to dangerous levels, prompting the Fed to reverse course abruptly. It hiked interest rates at the fastest pace in decades to cool the economy and tame prices. This pushed mortgage rates from around 3% in 2021 to over 7% by 2023. Typically, one would expect higher rates to tamp down home prices (since buyers can afford less), and indeed, some froth came off in late 2022. But as of 2025, home prices remain near record highs in most of the country. The price declines have been modest at best while borrowing costs doubled. The result is the worst of both worlds for new buyers: elevated prices and expensive mortgages. The housing market has effectively priced out a huge share of Americans, even many with decent incomes. Less than 20% of consumers now believe it’s a good time to buy a home, a drop from nearly 70% who felt optimistic just before the pandemic. The era of ultra-low rates has left a legacy of sky-high housing costs, which today’s higher rates have only made more painful.

The Fed’s Mortgage Buying Spree

Low interest rates weren’t the Fed’s only tool for propping up the housing market. In the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, the Federal Reserve undertook an unprecedented mortgage bond-buying spree, directly intervening to support home prices. Starting in 2009, the Fed began purchasing trillions of dollars in mortgage-backed securities (MBS)—the bundles of home loans that banks and investors trade. By becoming the buyer of last resort for MBS, the Fed aimed to push down mortgage rates and inject liquidity into the collapsing housing market.

Although not one that was well-publicized or widely understood by the public, this was essentially a massive bailout. Many major banks were on the brink, holding toxic mortgage assets that nobody else wanted. The Fed stepped in, hoovering up those securities to stabilize their value and keep credit flowing. In doing so, it also artificially inflated demand for mortgages, benefiting banks and lenders while directly driving up home prices (since cheaper mortgages tend to lead to pricier homes).

Over the next decade, the Fed repeatedly expanded and maintained a massive stockpile of MBS as part of its quantitative easing programs. So long as the Fed sat on this hoard of mortgage bonds, it signaled to markets that mortgage rates would remain suppressed. Home prices that might have fallen (or risen more slowly) were instead propped up by the Fed’s heavy hand. Former investment banker Alex J. Pollock famously observed that the Fed had effectively turned itself into the world’s largest savings and loan institution, with a mortgage portfolio larger than that of any private bank. To help visualize the Fed’s intervention, consider the timeline of actions and its impact on housing:

- 2001–2004: In the early 2000s, Fed Chair Alan Greenspan slashed short-term interest rates to 1%, a 40-year low, hoping to lift the economy out of recession. Cheap credit flowed into the housing market and helped inflate a housing bubble in the mid-2000s. (Greenspan later argued the bubble was a global phenomenon, but even he conceded that the 1% rates “lowered interest rates on adjustable-rate mortgages,” fueling a home buying surge.)

- 2008–2012: After the housing bubble burst spectacularly in 2007–08, the Fed sprang into action to bail out the mortgage market. Starting in 2009, it launched QE1, buying $1.25 trillion in MBS, which made mortgage credit cheaper, fueling a wave of refinancing. While banks lost money on these refinancings, home prices, which had been plummeting, stabilized and then began rising again by 2010–2011.

- 2013–2014: With the recovery still shaky, the Fed initiated another round of bond-buying (QE3), snapping up hundreds of billions in MBS to further stimulate asset prices and force down mortgage rates. This pumped more air into housing values. By 2014, the Fed’s balance sheet held an astonishing volume of mortgages, and home prices had regained or exceeded their mid-2000s peak in many areas.

- 2018–2019: Recognizing the risk of an overinflated market, the Fed belatedly began to taper its holdings. It allowed some mortgage-backed securities (MBS) to roll off (mature without reinvestment), thereby shrinking the MBS stockpile slightly. Sure enough, home price growth finally leveled off during this period. But the respite was short-lived.

- 2020–2021: When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the Fed went into crisis-fighting mode and opened the floodgates once again. It slashed interest rates back to zero and embarked on a new buying frenzy, including over $1 trillion in MBS purchases in 2020 alone. This firehose of liquidity, combined with pandemic-driven housing demand, sent home prices skyrocketing with historic speed. From mid-2020 to late 2022, U.S. home prices saw their fastest climb on record—a pandemic housing boom supercharged by Fed policy.

By buying and holding trillions of dollars in mortgage assets, the Fed distorted the housing market and artificially propped up home prices. Prices that would have collapsed in 2008 were rescued and reflated. Later, prices that might have cooled in 2019 were kept high by the Fed’s reluctance to fully unwind its position. Even now, as of 2025, the Fed still sits on roughly $2.3 trillion of agency MBS (about 30% of all U.S. mortgage-backed securities) on its balance sheet. This overhang means the Fed is effectively still subsidizing housing demand because unloading those assets would risk pushing mortgage rates higher and home prices down. Fed officials have been extremely cautious in shrinking their mortgage holdings, explicitly to avoid crashing the housing market. They know that if they dump MBS or allow a rapid fall in prices, they’d face backlash for causing “deflation” in home values. In short, the Fed’s priority has been to prop up asset prices (to protect banks and stimulate wealth effects), and the result has been the inevitable inflation of the housing market bubble.

Housing Affordability at a Breaking Point

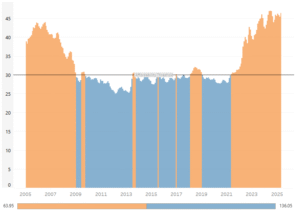

All of these factors—years of easy money, deliberate asset inflation, and now higher interest rates—have culminated in a severe affordability crisis. As of mid-2025, housing affordability in the U.S. has fallen to its lowest levels in decades. The Atlanta Federal Reserve’s Home Affordability Index shows a 45% decline in affordability from 2012 to 2023. In other words, a household that could comfortably buy a median-priced home a decade ago can no longer do so on the same income. This deterioration began even before the recent spike in inflation and rates in 2021, when mortgage rates were still near historic lows. That was the height of the pandemic housing boom when home prices were leaping 15-20% per year in many cities. Incomes couldn’t keep up with that explosion in prices.

Now layer on the impact of rising interest rates in 2022–2023. According to one estimate, the typical U.S. household in 2025 would need a $18,000 raise (relative to its 2019 income) to afford a median-priced home today. The reason is twofold: median home prices are much higher, and mortgage rates have more than doubled from around 3% to 6.75%. The combination means the monthly payment on a median home has shot up beyond what the median income household can manage. Buying used to be cheaper than renting in many markets, but that has flipped. Now, owning a home typically costs more per month than renting the same home, even assuming a 10% down payment. This is a complete reversal of the old conventional wisdom that it’s better to buy and build equity. Millions of Americans who would prefer to purchase a home are stuck renting because they simply cannot qualify for the mortgage or muster the down payment under these conditions.

Housing costs absorb nearly 45 percent of the typical American income today, up from roughly 30 percent a decade ago. Source: The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

According to the National Association of Home Builders, nearly 75% of U.S. households are “priced out” of the median new home as of early 2025. Three out of four families can’t afford what is supposed to be an average starter home. In high-cost states like California or New York, the situation is even more dire. For instance, in San Francisco, a median-income household would need to put down $875,000 (nearly twice their annual income) to keep monthly costs below the affordability threshold. Even in more typical markets, down payments of around $70,000 are now needed for a median home, far above what most first-time buyers have saved. It’s no wonder the homeownership rate has been declining. From a peak of 69% in 2004, it fell to around 63% by 2016 and remains several percentage points lower than its peak today. After a slight uptick during the pandemic (as wealthier households bought second homes), ownership is again slipping as young buyers drop out of the market.

Perhaps the most telling sign of distress is the shift in age among Americans. The median age of a U.S. renter is now 42 years old, up from 36 in 2000. People are renting well into what used to be prime years for homeownership. “Renters are starting families and staying renters,” noted Orphe Divounguy, a senior economist at Zillow, calling it a clear “symptom of the affordability challenges we’re facing.” Younger adults, who in previous generations would be first-time buyers, are delaying that step indefinitely, if not giving up on it entirely. A recent survey found that over half of American renters believe they may never be able to afford to own a home. The cultural norm that each generation will own homes (often earlier than their parents did) is quickly becoming a thing of the past.

The American Dream Deferred

Housing isn’t just another asset class. It’s woven into the American Dream and the financial security of families. And when home prices rise far faster than wages, the fallout can be profound. Those who already own homes (typically older and wealthier Americans) see their equity grow, and their wealth increases on paper. Meanwhile, those locked out of ownership (often younger and less affluent people) are stuck paying rent and missing out on the primary wealth-building mechanism for the middle class. The result is a generation of Americans who feel left behind and frustrated. They’re doing “all the right things”—getting an education, finding jobs, and saving what they can—yet homeownership remains out of reach due to macroeconomic forces beyond their control.

“With borrowing costs elevated, house prices at all-time highs, and inventory scarce, it is no wonder that households are downbeat about home buying,” observed Thomas Ryan, a housing economist. Life plans are being altered. Many young couples have delayed starting families because they lack stable housing. People in their 30s and 40s find themselves living like perpetual renters, unable to put down roots. From lower birth rates to mental health concerns, the impact of the current housing market goes far beyond just financial implications.

Communities also feel the strain. Workers who can’t afford housing near job centers may endure long commutes or drop out of local labor markets, hurting economic productivity. Essential workers, such as teachers, nurses, and first responders, are often priced out of the very communities they serve. This can lead to labor shortages or force municipalities to consider subsidized housing options to retain talent. A tight housing market with sky-high rents also means more households are one crisis away from eviction or homelessness. In many cities, rising housing costs have contributed to increases in homelessness and a greater need for social services.

Another consequence is the entrenchment of a phenomenon analysts call housing lock-in. During the low-rate era, millions of homeowners refinanced or purchased homes with 30-year mortgages at rates of 3% or less. Now that rates are double or triple that, those owners are reluctant to sell. They don’t want to give up their rare, low-rate loans and face higher rates on a new purchase. As Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted, “People are locked in. They can’t afford to get out of their house because the cost of getting into a higher-priced mortgage would be a lot.” This has created a severe inventory shortage as fewer existing homes are hitting the market, which in turn keeps prices from falling. Potential move-up buyers often stay put, limiting options for first-time homebuyers. In some areas, the housing market has become almost frozen because nobody wants to trade a 3% mortgage for a 7% one. An unintended legacy of the Fed’s prior low-rate policy, this lock-in effect perpetuates the supply-demand imbalance, thereby maintaining high prices. This means the affordability crisis could persist even if demand softens, as supply remains so constrained.

Socially and politically, housing affordability has shot to the top of the agenda, with polls showing that voters across the spectrum are concerned about housing costs. A Redfin survey found over half of respondents said affordability would influence their vote in the 2024 elections. Frustration is brewing, particularly among younger Americans, who feel the system is rigged against them. And while leaders have proposed a myriad of solutions, the reality is that there is no quick fix to the housing affordability crisis.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Americans face a delicate and precarious path out of this housing dilemma, with the Federal Reserve now caught in a bind of its own making. On one hand, it could try to relieve some pressure on homebuyers by cutting interest rates again. Lower rates would, in theory, bring down mortgage costs and perhaps spark more construction. However, any move to significantly cut rates in 2025 risks reigniting the very inflation that forced rates up in the first place.

Fed Chair Powell has repeatedly stressed that the “absolute best thing we can do for housing is to restore price stability,” meaning curbing inflation overall. From the Fed’s perspective, stable prices and a strong economy will eventually allow for a gradual easing of rates without setting off another inflationary spiral. Powell has indicated that once inflation is sustainably back to 2%, “mortgage rates will come down,” but he cautioned he “doesn’t know when that will happen.” Put simply, the Fed is prioritizing the fight against inflation over immediate housing relief, calculating that it’s a necessary trade-off.

On the other hand, even if/when the Fed can safely lower rates, housing supply constraints remain. As Powell acknowledged, “We’re still going to have a housing shortage in many places.” Simply making mortgages a bit cheaper won’t fix the underlying shortage of homes relative to households. Years of underbuilding, restrictive local zoning, and pandemic-related supply chain issues mean the U.S. is millions of housing units short of what is needed to meet demand. So, while a modest drop in rates, from 7% to 5%, would improve affordability somewhat, it could also reignite demand and bump prices back up if supply doesn’t improve. It’s a catch-22: the cure for high prices is more supply (building), but more demand spurred by cheaper credit could outpace any new construction. Policymakers beyond the Fed will need to address the supply side through incentives for building, loosened zoning regulations, and investment in affordable housing.

There’s also the risk of a broader economic downturn. If the Fed’s rate hikes (or some other outside shock) tip the economy into a recession, we could see unemployment rise and income growth stall, which would further harm affordability for those who lose their jobs. However, a recession might also burst some of the housing bubbles, leading to price corrections in overheated markets. It’s a harsh remedy, but in previous cycles, housing costs have only really improved for buyers after a market correction or recession reset prices.

The Federal Reserve’s prolonged experiment with easy money has left Americans with a housing market that is severely out of balance, and rebalancing could necessitate a painful correction. Once asset prices are inflated, bringing them gently back to earth is easier said than done. For now, millions of Americans remain on the sidelines of homeownership, watching and waiting for their chance at the American Dream. Whether that dream is merely deferred or becomes permanently out of reach for a generation remains to be seen.