By Preserve Gold Research

The European Central Bank’s decision to expand access to euro liquidity is more than a technical change. It signals a shift in power and trust within an increasingly uncertain global order.

Announced at the Munich Security Conference, this plan is the first time an ECB president has addressed that forum. The ECB will make euro funding globally available and permanent. Starting later this year, almost any central bank can borrow euros from Frankfurt during a crunch, up to €50 billion, unless blacklisted. ECB Chief Christine Lagarde calls the move preparation for “a more volatile environment.” The goal is to prevent fire-sale liquidations of euro assets in a crisis that could “hamper the transmission of our monetary policy.”

Beyond technical details, this move has strategic implications. By extending its financial safety net beyond Europe, the ECB aims to expand its global influence. Lagarde says this facility “reinforces the role of the euro” by giving investors and central banks confidence they can access euro liquidity in times of need.

Why roll out a global euro backstop now? One immediate trigger is the turbulence of recent years, which has shaken confidence in the U.S. dollar’s once-unquestioned dominance. Lagarde and her colleagues noted that international investors are reassessing the dollar’s status. Unpredictable U.S. economic policies are at the heart of this shift. European officials have pointed to disruptive trade tariffs and policy shocks under President Donald Trump as a wake-up call. They argue these measures have “upended long-standing ties” and forced Europe to question whether it could rely on the U.S. Federal Reserve’s dollar swap lines in a future crisis.

In that context, expanding the euro’s reach serves two purposes: bolstering its global standing and hedging against alliance risk. Central bank lending spreadsheets, though technical, reveal real-time geopolitical shifts by showing how liquidity and currency exposure reflect evolving financial alliances. The ECB’s global offer of euros acts as both an economic tool and a geopolitical message, signaling Europe’s intent not to let its currency lag as the balance of monetary power changes.

Fed Swap Lines and the Dollar’s Sphere of Influence

For decades, dollar liquidity lines have underpinned global financial stability and reinforced U.S. geopolitical influence. The Federal Reserve’s swap and repo facilities provide emergency dollar access to other central banks, ensuring liquidity during periods of stress. In 2008 and 2020, these lines were critical in preventing global funding crises. The Fed has effectively served as lender of last resort for the global dollar system, on its own terms.

The Fed keeps permanent swap lines with five allied central banks: the euro area, Canada, the U.K., Japan, and Switzerland. In crises, it has extended temporary lines to a few more. This “swap line club” is shaped by economic exposure and geopolitical factors.

During the 2008 financial crisis, for example, the Fed chose its swap partners with two filters in mind. The first was where U.S. banks were most exposed. The second was where diplomatic ties ran deepest. Policymakers understood the overlap. Stabilizing allied financial systems was more for self-protection than anything else—a way to prevent foreign stress from ricocheting back into U.S. markets.

Many emerging economies have never enjoyed that kind of assumed access. When dollar funding tightens, they are more often left to absorb the shock, improvise in markets, or turn to the IMF. The asymmetry has not gone unnoticed. In parts of Asia, it has been institutionalized into policy.

The Chiang Mai Initiative is a $240 billion swap arrangement among ASEAN countries plus China, Japan, and South Korea. It emerged from the recognition that Fed swap lines are a privilege, not a guarantee, for those beyond Washington’s inner circle. As Japan’s central bank governor, Kazuo Ueda, put it, a “multi-layered approach” to financial safety nets is prudent. A single backstop can prove conditional or unavailable when it’s most needed.

Ueda’s point captures a broader reality. Liquidity lines are as much about politics as economics. Who gets access to easy dollars, and who doesn’t, can cement alliances or sow resentment. The Fed’s dollar swap lines have quietly reinforced U.S.-centric networks of influence. They stabilize during crises. But they also remind the world that the dollar’s umbrella opens primarily over Washington’s friends.

Even members of the privileged dollar club are showing signs of unease. By 2025, European central bankers were debating contingency plans in case the Fed’s lifeline became politically constrained. Trump-era policies raised fears among many allies that financial ties could be used strategically rather than neutrally. The mere fact that such scenarios are being discussed reveals something. The dollar’s safety net, for all its scale and reliability, carries political risk. Once that realization took hold, it created space for others to step in with liquidity backstops of their own.

Inside the ECB’s Plan to Boost the Euro’s Global Role

Against that backdrop, the ECB’s new global euro backstop reads as a bold bid to widen the circle of trust. This new approach centers on the euro rather than the dollar. Until now, the ECB’s so-called EUREP facility has been limited. It was offered mainly to a few neighboring countries in Eastern Europe.

Lagarde has advocated for change, calling repo facilities a “tool to boost the euro’s global reach.” Starting in Q3 2026, the ECB will broaden access. Any central bank, except those with serious reputational issues, can request euro loans against high-quality collateral.

Lagarde states the goal is to “boost confidence to invest, borrow and trade in euros.” The assurance is that access will be there during market disruptions. To enhance the facility’s appeal, the ECB is standardizing terms, lowering interest rates, and relaxing borrowing caps. The expectation is that this reassurance will encourage central banks to hold more euro assets.

At one level, this is about financial stability. Europe is fortifying defenses against any future funding squeeze that could force investors to dump euro-denominated assets in a panic. Such panic would undermine Europe’s economy and the transmission of its policies. Providing foreign central banks with an outlet for euro liquidity functions like fire sprinklers in a high-rise. The point is not to use them, but to ensure they are there when smoke begins to spread.

This move also addresses currency competition. By offering a facility similar to the Fed’s, the ECB encourages countries to view the euro as an alternative source of stability. Each time a central bank opts for euros over dollars in a crisis, it moves the system toward greater multipolarity. European policymakers acknowledge the euro will not replace the dollar soon. They aim to gradually reduce the dollar’s dominance.

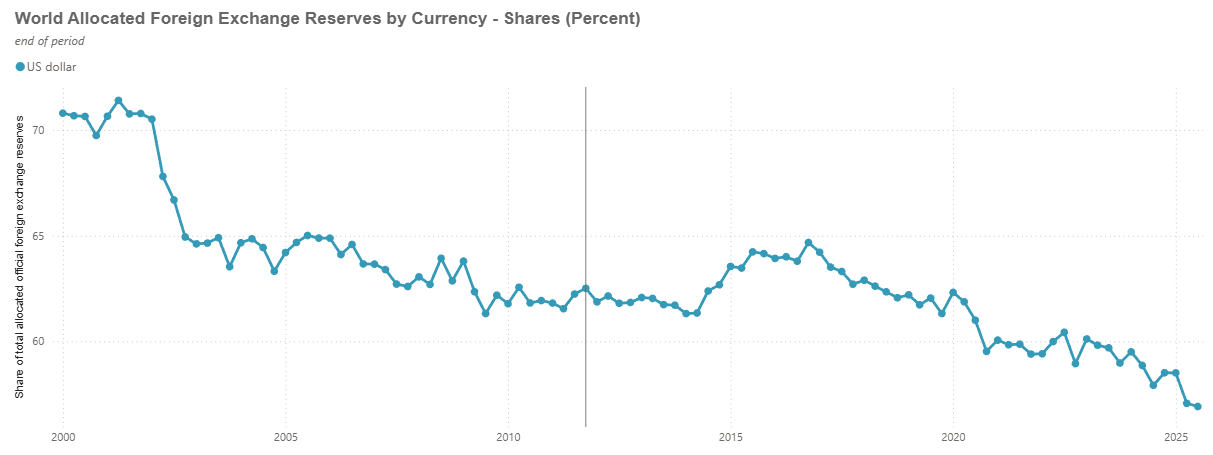

Timing matters, and Europe knows it. Over half of global foreign exchange reserves are still held in U.S. dollars. That share has been shrinking over the past decade. The euro has maintained roughly a 20% share and could edge higher if dollar confidence continues to wobble. In the past year alone, it has appreciated about 14% against the dollar.

None of this implies Europe believes it can replace the dollar. Austria’s central bank governor Martin Kocher explained that “it’s not an objective” to have the euro much larger internationally, but given global trends, Europe “might be forced to do so” and must be prepared. The reluctance is revealing. The ECB is moving beyond its traditional comfort zone, not as vanity, but as necessity, “part of the mandate to sustain financial stability” in a world where the usual anchor has become less predictable.

Why Europe Is Hedging Against Dollar Dependence

The expansion of euro liquidity has been driven by an uncomfortable truth: transatlantic economic trust has been tested. The Trump era has forced European policymakers to reexamine assumptions about U.S. reliability. In interviews, more than a dozen European central banking officials admitted they “worry” Washington might one day weaponize its financial lifelines. Much of this anxiety crystallized in April 2025 during the so-called “Liberation Day” tariffs, when abrupt trade measures jolted markets, strained European banks’ funding, and laid bare Europe’s continued exposure to sudden shifts in U.S. policy.

At the height of that turmoil, the unthinkable became thinkable, and European policymakers began asking questions. What if the Fed’s dollar swaps are not there when needed? What if an American president leans on the Fed, directly or through its Board, to withhold dollar liquidity as pressure on a foreign government? Such scenarios have been virtually absent from post-war financial history. The Fed is supposed to be above politics, and U.S.-Europe ties have long been treated as bedrock. But by late 2025, European officials were seeing enough smoke to wonder whether the firebreaks still hold. Trump’s policies had “upended long-standing ties” and, in their eyes, had put the Fed’s independence in doubt.

Europe’s internal response has been telling. Officials have explored backup plans to reduce reliance on the dollar. One radical idea has been to pool hundreds of billions of euros’ worth of foreign currency reserves from the euro zone and allied countries into a common pot of dollars, effectively a self-insurance fund that could be tapped if the Fed’s window ever closes. It would be a European version of the Chiang Mai Initiative, but focused on dollar liquidity. The fact that the idea gained traction at all shows how real the concern has become.

While fears eased somewhat as Fed Chair Jerome Powell assured counterparts that the Fed has no intention of cutting off swap lines, the episode has left a residue of caution. European regulators have been pressing banks to diversify funding sources, encouraging them to secure dollar funding from markets in Asia or the Middle East as a hedge. This is the emotional and strategic backdrop for the ECB’s global repo facility. By providing an independent liquidity backstop, Europe reduces the worst-case vulnerability of relying on a single lifeline. It’s strategic redundancy, the financial equivalent of building an alternate bridge while still using the main one.

European officials have framed the move as Europe stepping up its responsibilities in a harsher world. Kocher has linked the euro facility to Europe’s “turbulent relationship with the United States” and “greater economic competition from China,” forces he says are “shaking the foundations” of policy and pushing the EU to rethink its global role. EU leaders are also being given a “checklist” of tasks to strengthen Europe’s financial architecture alongside this move, including long-debated projects such as completing a banking union and deepening capital markets. The subtext is hard to miss. If Europe wants to rely less on Washington, it has to strengthen its own foundations.

RMB Internationalization and the Rise of Parallel Backstops

Europe’s push to expand the euro’s global role is also part of a broader contest over currency influence in a fracturing geopolitical landscape. China sits in the background of every serious European discussion about financial autonomy. Beijing has been working for years to increase the international use of the renminbi, and progress, though slow, is persistent. President Xi Jinping has declared that China should “build a powerful currency that could be widely used in international trade, investment and…attain reserve currency status.”

To that end, the People’s Bank of China has established bilateral swap lines with more than 40 countries, from major economies to numerous emerging markets. These swaps allow foreign central banks to access the yuan if needed, theoretically making it easier to use the RMB for trade and finance. The footprint remains modest, but Beijing is playing the long game.

By encouraging RMB invoicing, building payment infrastructure such as CIPS as an alternative to SWIFT, and using swap lines as a diplomatic tool, China is laying the groundwork for a world in which the yuan’s role expands. Western sanctions on Russia in 2022 provided a real-world boost. Cut off from dollars and euros, Russia increased its use of RMB for trade and reserves. Other countries have been thinking more seriously about diversification as sanction risk becomes part of the geopolitical weather.

The ECB is reading the same map. When Lagarde argues this is the moment for the euro to gain market share, it’s partly because Europe sees a window that will not stay open. A more multipolar currency world is emerging, one in which the dollar, the euro, and eventually the renminbi provide layers of redundancy. That could be more resilient. But it could also be more fractured if currency blocs align with geopolitical camps.

A Fragmenting Financial Safety Net?

As the global financial safety net becomes more distributed across currencies, promise and peril arrive together. Multiple major central banks capable of providing emergency liquidity in their own currencies could make the system more robust. In a future contagion, the Fed, ECB, and even the PBOC could coordinate, flooding the system with dollars, euros, and yuan, each stabilizing its markets and, in turn, reinforcing the whole. More “circuit breakers” can reduce the risk that a crisis in one region spirals into global panic. The ECB’s facility adds another doctor on call to a system that has long depended on one.

The pessimistic view is equally plausible. A more multipolar safety net could become more fragmented, mirroring geopolitical fault lines. If trust erodes among major powers, central banks may become less willing to coordinate and more focused on their respective client states. The result would be a patchwork in which countries must rely on their patron currency provider: Washington for some, Frankfurt for others, and Beijing for others still. This patchwork can leave holes. Countries outside blocs can fall through the cracks, and rival blocs can be reluctant to backstop each other even when doing so would be mutually beneficial.

Europe’s own contingency planning has already demonstrated how such fractures can emerge. The fact that European officials have contemplated a scenario in which the Fed might refuse to support shows how quickly politics can intrude into what was once treated as technocratic infrastructure. It’s not difficult to imagine a future U.S.-China standoff in which the Fed and PBOC support their partners but avoid supporting the other’s system. In that scenario, the euro might even become a neutral currency for states that prefer not to choose sides.

Multiple liquidity providers also introduce competition in standards and conditionality. The IMF has traditionally served as a lender of last resort with explicit policy conditions. Swap and repo lines tend to be faster, more discretionary, and less attached to macroeconomic reform. That can be beneficial by reducing the need for politically toxic bailouts. It can also allow governments to delay addressing underlying problems if temporary liquidity becomes a substitute for structural adjustment. The currency safety net a country relies on can shape how crises are managed and how accountability is enforced.

From the U.S. perspective, a shared safety net also implies a gradual dilution of influence. Fed swap lines have been an instrument of soft power and a reinforcement of the dollar’s centrality. If more countries rely on the ECB in emergencies, some may incrementally reduce their dollar reserves in favor of euros, and their financial systems may knit more closely into European markets. Over time, that can weaken the U.S.’s financial sway at the margins. It can also reduce the effectiveness of U.S. sanctions if alternative liquidity and settlement routes become more viable.

What the Global Euro Backstop Signals for Investors

In the ledgers of central banks, one can read the writing on the wall of the global order. The ECB’s worldwide liquidity line may appear to be a technical adjustment to repo operations, but its significance is geopolitical. It reflects a world in which economic alliances are being tested by populism, protectionism, and great-power rivalry.

Europe’s steps suggest allies are not abandoning the U.S., but they are seeking insurance and agency within the alliance. The coming years will test how parallel liquidity lines function when the next storm arrives. Whether they complement one another or expose new fractures will depend on the trajectory of U.S.-European and U.S.-China relations. If rivalry intensifies, even central bank tools may find themselves pulled into political crosscurrents.

For now, the existence of a “global euro” backstop serves as a bellwether. Multipolarity in finance can no longer be ignored, and a more complex monetary landscape calls for resilience at both the personal and institutional levels. Just as central banks diversify their backstops, individuals may find value in diversifying their own stores of wealth—including assets that sit outside the direct reach of any single government’s policy shifts. The guardrails of globalization are being rewired. How the United States responds will shape whether this transition produces a steadier balance or a more contested order.