By Preserve Gold Research

Europe’s planned digital euro is no bolt from the blue. This central bank digital currency (CBDC) has been years in the making, telegraphed through studies and pilot programs since 2020. European officials have presented it as a natural evolution of money, promising convenience, innovation, and even “freedom of choice” in payments. But behind the reassuring language lies a more sobering reality.

The digital euro is poised to extend institutional control over finance to an unprecedented degree. For Americans watching from afar, Europe’s experiment offers a glimpse of how digital currencies could quietly reshape the balance of power between citizens and the state. While the tone in Brussels is optimistic, emphasizing modernization and “monetary sovereignty,” the undercurrents of increased surveillance and erosion of financial autonomy are hard to ignore. What follows examines how the digital euro’s gradual debut is setting the stage for a new system of control, and why its implications reach well beyond Europe’s borders.

How Europe Normalized the Digital Euro Over a Decade

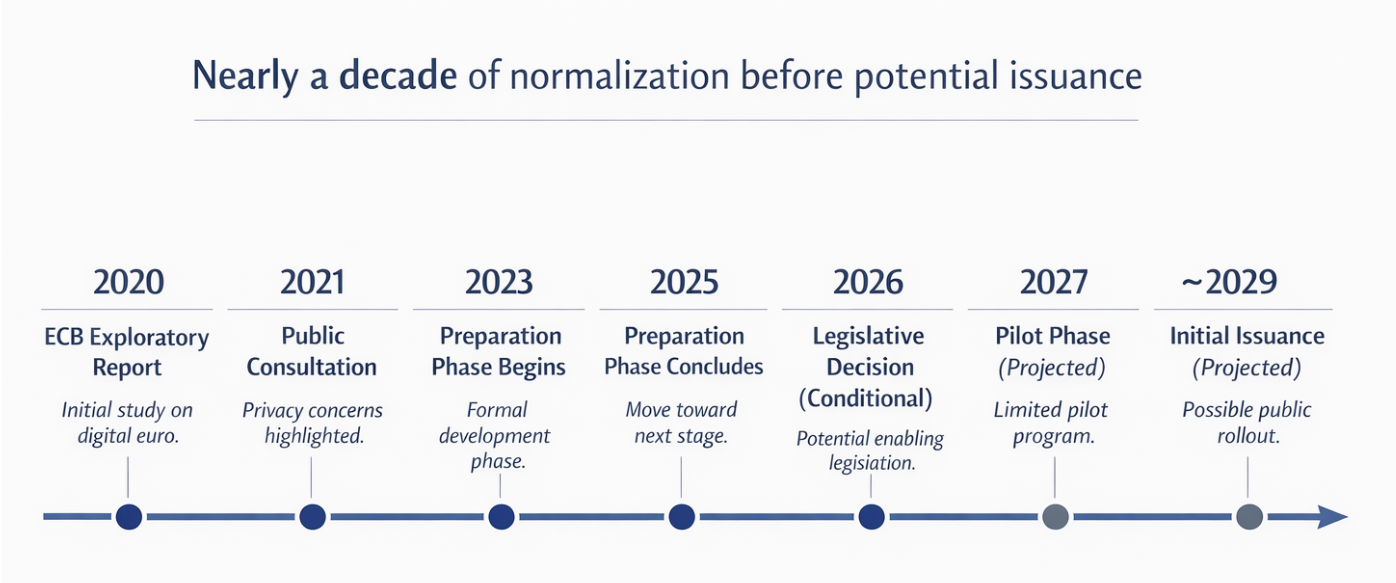

The European Central Bank (ECB) took its first steps toward a CBDC in October 2020 with a detailed report exploring a digital form of the euro. What followed was a multi-year journey of investigations, consultations, and preparatory work. By late 2023, the ECB launched a formal preparation phase, collaborating with national central banks and private partners to hash out technical designs and use cases.

This phase concluded successfully in October 2025, prompting the ECB’s Governing Council to green-light moving to the next stage. If enabling legislation passes by 2026, a pilot could begin in 2027, with initial issuance around 2029. Europe’s monetary authorities have given themselves nearly a decade to normalize the concept and smooth the path to deployment.

Such a gradual rollout has meant the digital euro is hardly a surprise to those paying attention. High-level political backing has been clear. Eurozone leaders have called for accelerated progress, framing the project as essential to keeping pace with technological change. “The euro, our shared money, is a trusted sign of European unity,” ECB President Christine Lagarde affirmed in late 2025, “We are…preparing for the issuance of digital cash”. As Europeans use physical cash less and electronic payments more, officials argue a public digital currency is the next logical step—necessary to “future-proof Europe’s monetary system” and preserve the euro’s relevance in a digital age.

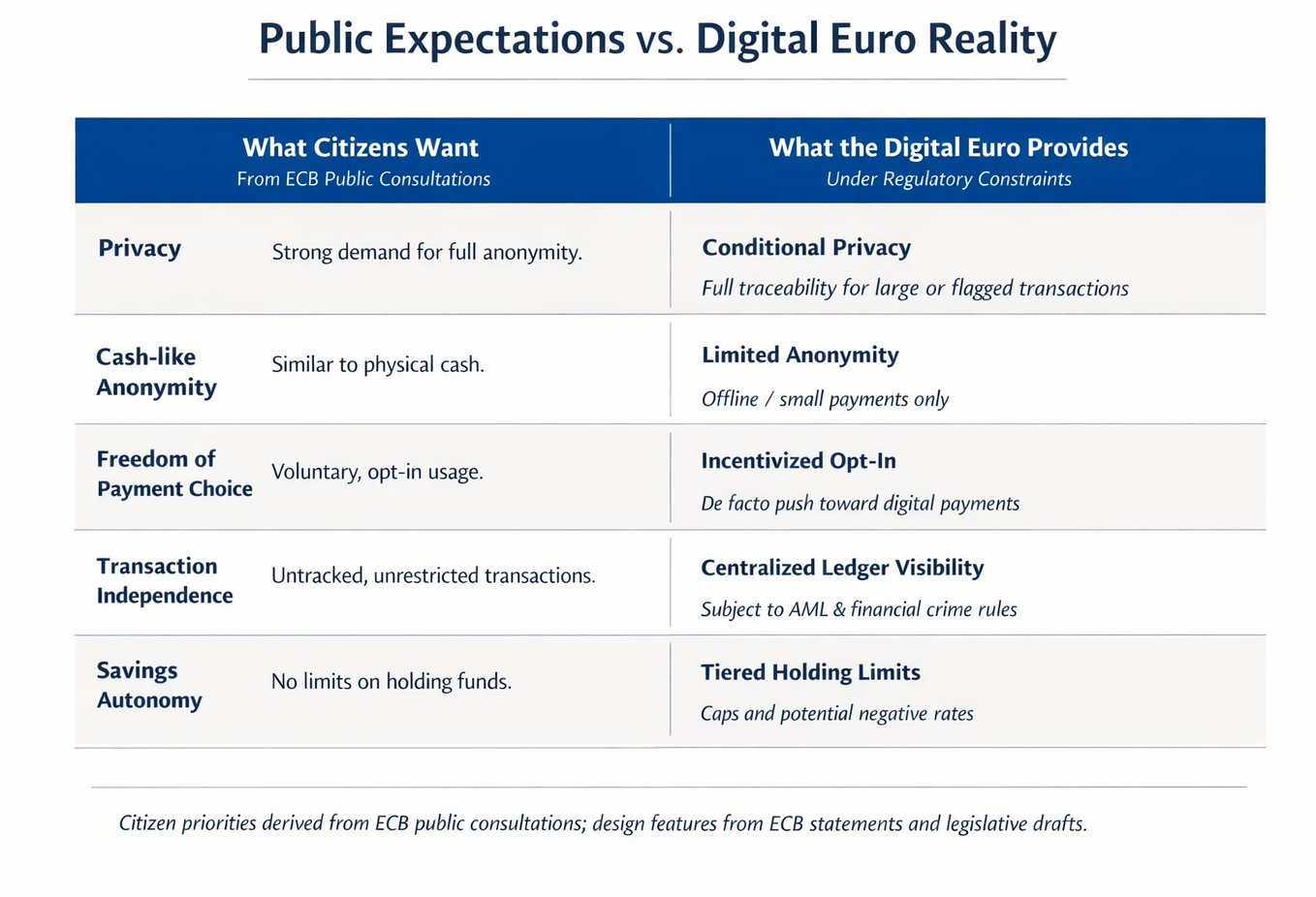

On the surface, Europe’s approach has been inclusive. The ECB has gathered feedback from experts, industry, and the public. A 2021 public consultation drew over 8,000 responses and revealed what citizens care about most: privacy was the top concern for 43% of respondents, far outranking other features. Europeans signaled they would only accept a digital euro if it protects their data and mimics the anonymity of cash to some degree. “A digital euro can only be successful if it meets the needs of Europeans,” noted ECB board member Fabio Panetta, acknowledging the primacy of privacy in the design.

These consultations shaped early design principles, including proposals for offline transactions and holding limits to prevent excessive migration of bank deposits. By integrating feedback and proceeding in small steps, the ECB has lent the project an air of inevitability rather than disruption. Each announcement, whether about a draft rulebook or the selection of technology providers, has been framed as just another incremental milestone.

Yet, the slow pace also serves a strategic purpose. The extended timeline normalizes the idea and blunts opposition. By the time the digital euro arrives, it’s meant to feel less like a leap and more like the final piece of a long-assembled puzzle. What looks like prudence in implementation is also a tactic to transform how money works, and who controls it.

The Official Narrative: Innovation, Inclusion, and Sovereignty

European authorities have been eager to highlight the digital euro’s benefits, portraying it as a boon for consumers and the broader economy. In the official telling, the CBDC will complement cash rather than replace it, preserving simplicity, security, and privacy while updating the euro for a digital world.

ECB officials stress continuity and choice. Citizens, they say, will remain free to use cash or digital euros as they prefer, with freedom of payment enshrined as a core principle. The language of liberty is deliberate. Project leaders have argued publicly that a digital euro would preserve, not diminish, people’s freedom to choose how they pay.

Financial inclusion is another pillar of the case. Today, electronic payments in the eurozone are dominated by private banks and card networks, many of them non-European. The ECB argues that a public digital currency would offer a risk-free option for storing and transferring money, accessible to all.

Proponents like economist Hans Stegeman of Triodos Bank argue that the digital euro, if designed right, could “guarantee universal access to safe and affordable payment options, promoting financial inclusion.” Officials also emphasize innovation. By providing common standards and a public platform, the digital euro could enable private firms to build new services on top of it, much as the internet enabled waves of digital commerce.

Perhaps the most politically charged promise is monetary sovereignty. European policymakers have grown uneasy about reliance on foreign payment systems and the dominance of the U.S. dollar in global finance. Private dollar-linked stablecoins and U.S.-based payment networks have sharpened fears of “digital dollarization.”

More than 70 European economists recently warned that without a digital euro, “Europe will lose control over the most fundamental element in our economy: our money.” In their view, a public CBDC is the only credible defense against deeper U.S. influence over European payments and a necessary pillar of economic resilience. Christine Lagarde herself indicated that the digital euro is partly motivated by international strategy, to strengthen Europe’s role in international markets and even reduce dependency on the U.S. dollar over time.

European officials have been careful to couch these goals in terms of sovereignty, stability, innovation, and inclusion. The European Commission’s draft legislation on the digital euro, unveiled in mid-2023, stresses high privacy standards and even proposes legal protections for paying with cash alongside digital money. Regulators like the European Data Protection Board have weighed in to ensure data safeguards are written into the law. All of this is meant to reassure the public that the digital euro will preserve Europeans’ freedom of choice and privacy and protect Europe’s monetary sovereignty and economic security.

However, as appealing as this sounds, it tells only half the story. The rhetoric of freedom and sovereignty addresses public anxiety directly, yet it also preempts deeper scrutiny. The true impact of the digital euro cannot be understood without probing the darker underside of what CBDCs enable.

Control Sits Beneath the Digital Euro’s Modernization Story

Critics say beneath the language of public interest lies a desire to reassert control over a financial system that has grown increasingly digital, decentralized, and difficult for authorities to steer. European policymakers have watched with unease over the past decade as Bitcoin, stablecoins, and Big Tech payment systems proliferated beyond their full reach. To them, a CBDC is a way to regain the steering wheel.

As policy analyst Nicholas Anthony observed, “Nearly every central bank digital currency has that in common—they exist to facilitate control.” And the digital euro is no exception. For all the talk of sovereignty, at heart it’s about the state tightening its grip on money in an era when money is becoming digital and borderless.

This push aligns with a longer trend in European financial regulation. Long before the CBDC, the EU incrementally narrowed the space for unmonitored transactions. By 2027, cash payments will be capped at €10,000 across the bloc, with some countries already enforcing far lower limits. Anonymous prepaid cards are tightly restricted, and privacy-focused cryptocurrencies have been excluded from exchanges. These measures are usually justified in terms of fighting money laundering, tax evasion, or terrorism financing. But collectively, they have steadily chipped away at the ability to transact beyond official oversight. If preserving freedom of payment was a top priority, as has been stated, authorities might resist such constraints. Instead, the pattern points toward control.

A digital euro would hand authorities powerful new levers of control that cash and decentralized cryptocurrencies don’t allow. Transactions could be recorded in real time, creating unprecedented visibility into spending behavior. Authorities would gain the ability to see who spends what, where, and when.

The experience of China’s digital yuan, closely studied by European officials, illustrates the grim possibilities. Trials there have included programmable features such as expiration dates, forcing funds to be spent before they disappear. Such mechanisms allow policymakers to penalize saving and compel consumption in downturns. They also open the door to behavioral conditioning. If every payment depends on state approval, then citizens can be pressured or prevented from spending in ways the state deems undesirable. It’s a scenario where financial freedom could cease to exist in any meaningful sense.

European officials insist safeguards will prevent abuse, pointing to data-protection laws and proposed privacy features such as offline transactions for small payments. Yet these protections are explicitly limited. Larger or suspicious transactions would remain traceable, and the ECB has acknowledged that a digital euro cannot be fully anonymous without conflicting with financial crime rules. Privacy, in other words, would be conditional. Once an infrastructure of comprehensive visibility exists, its scope can be expanded through policy changes rather than technological leaps. In times of crisis, the temptation to do so is often strong.

The digital euro also opens new avenues for monetary intervention that blur into control. Central banks have long sought ways to enforce negative interest rates during downturns, a policy constrained by the ability to hold physical cash. In a digital-only environment, escaping such measures becomes far more difficult. The ECB has discussed tiered remuneration, under which holdings above a certain threshold would earn no interest or even incur penalties. While framed as a safeguard against bank disintermediation, such tools inevitably influence how individuals save and spend.

The Soft Launch Strategy Behind Europe’s CBDC

If the digital euro is a new control system, it’s being introduced with deliberate subtlety. Rather than impose a dramatic overnight change, European authorities are making the CBDC feel evolutionary. The plan is to start small, with limited scope, and gradually scale up—a textbook “soft launch”.

Early versions would impose strict limits on holdings and likely pay no interest, making the currency appear narrow in scope and unthreatening. These constraints are justified as protections for the banking system, but they also serve a political purpose. A modest, even boring, first iteration reduces public resistance. Banks, many of which oppose the project, are reassured that their role will not be immediately undermined.

European officials also stress that using the digital euro will be optional. Cash, they insist, will remain available across the euro area, and the digital euro will complement existing payment options. Legal protections for cash acceptance have been proposed alongside the CBDC framework. This opt-in framing is a hallmark of soft launches. Adoption is meant to feel optional until convenience, incentives, and network effects make participation the path of least resistance.

Experience elsewhere suggests how quickly voluntariness can erode. In China, the digital yuan began as an option but soon became difficult to avoid as salaries, benefits, and merchant systems migrated to the new rail. While Europe’s political context differs, the dynamics of scale are similar. Once government payments flow through digital euro wallets, opting out becomes costly in practice if not in law.

The architects of the digital euro are well aware that trust is key to uptake. They speak of transparency and stakeholder engagement at every step. The ECB has even promised to publish the source code of the digital euro system for scrutiny, and to involve citizen groups in its development. These measures sound comforting, but they are part of the soft sell. By letting the public peek under the hood, the ECB hopes to dispel images of an all-powerful Big Brother lurking in the code.

But transparency does not alter where authority ultimately lies. Rules, limits, and parameters can be changed by policymakers as circumstances evolve. A holding cap introduced to reassure the public can be raised or removed later. Support for cash today can give way to incentives that favor digital payments tomorrow. A system introduced for benign reasons can be repurposed as priorities shift. As the saying goes, “features can become bugs” depending on who is at the controls.

It should be noted that not everyone in Europe is on board with the digital euro’s direction. Some Members of Parliament worry about privacy, others about the cost and necessity of the whole venture. Civil-liberties advocates warn that even with guardrails, the existence of a CBDC infrastructure grants future governments powerful tools that may be misused in less benign contexts.

The ECB’s cautious pace reflects an awareness of this resistance. Should the European Parliament approve the framework in 2026, a trial period would follow, allowing officials to argue that fears were overblown. By the time full rollout arrives around 2029, using a digital euro could feel as routine as using a debit card. And at that point, the new control system will be quietly embedded in European life: an all-seeing monetary network that was eased in under the banners of modernization and choice.

The Digital Euro as a Test Case for Democratic Systems

Europe’s foray into CBDCs holds clear lessons for the United States and other democracies. For one, it illustrates two diverging philosophies on digital money. The U.S. approach emphasizes decentralized innovation through private, regulated digital dollars, while Europe asserts public control over the monetary core. American lawmakers have warned that a CDBC could enable surveillance incompatible with democratic norms, and have attempted to block or at least delay that possibility. Europe, however, has chosen to accept those risks in the name of sovereignty and competitiveness.

For Americans, the digital euro is a live test case. Its rollout will show how a CBDC functions in a large, advanced economy and what trade-offs emerge in practice. A smooth adoption could renew pressure on the U.S. to reconsider its stance to avoid falling behind. On the other hand, privacy scandals or perceived overreach in Europe would reinforce American skepticism.

There are also broader geopolitical considerations. The euro and dollar have long been partners and rivals in the global economy. Should the ECB’s project achieve its aim of reducing dependency on the U.S. dollar in international markets, the U.S. could see a relative erosion of its financial influence.

One reason the dollar is so dominant is that it’s the default currency of international trade and the backbone of global finance. The ECB is eyeing a digital euro that could be used beyond Europe’s borders (with some limits) and potentially make cross-border payments cheaper and faster. If successful, this could nibble at the edges of dollar hegemony. While the shift would likely be gradual, further fragmentation of today’s global monetary order would have far-reaching consequences.

Many Americans are also watching how the values of democracy and privacy fare in the European implementation. The EU boasts some of the world’s strongest data protection rules and a commitment to human rights. If even under those conditions a digital currency raises concerns of control, it underscores how intrinsic those risks are to the technology itself.

When Monetary Convenience Becomes Centralized Control

Europe’s digital euro is not just Europe’s business. It’s a bellwether for the future of money in open societies, and a live test of how quickly “optional” infrastructure becomes default architecture. For Americans wary of creeping overreach, the question is less whether the water boils and more whether anyone notices the temperature rising until the choice to step out has quietly narrowed.

Beneath the gradualism and the soothing rhetoric, Europe is building a financial system in which public authorities sit closer to the circuitry of everyday commerce. Official talk of freedom, privacy, and choice sits uneasily beside what a CBDC can do in practice: create visibility into transactions, expand compliance reach, and, over time, make monetary policy more direct and more individualized. None of this is shocking to those who have tracked the project’s arc. The destination (greater central oversight) has been obvious for years. The surprise, if it comes, will arrive later, once the rails are in place and “temporary” features harden into permanent norms.

For Europe’s leaders, the digital euro is a bid to secure monetary relevance and strategic autonomy in a digitizing world. For Europe’s citizens, it signals a shift in where financial freedom resides: less in the structure of the system and more in the restraint of whoever runs it. That is the real trade-off. A tool that can simplify payments and broaden access can also, under different incentives, become a mechanism for monitoring and influence.

For those of us watching from an ocean away, Europe’s experiment feels less like an abstraction and more like a preview. The question isn’t whether digital currency is “good” or “bad,” but who controls it, and how that control is exercised over time. In moments like this, resilience stops being about guessing the next policy decision and starts being about not putting all your financial eggs in one system. When money increasingly depends on permissioned rails and institutional goodwill, it’s natural for people to look for balance elsewhere. That’s why, when trust becomes conditional, time-tested stores of value like gold and silver find their way back into serious consideration.