By Preserve Gold Research

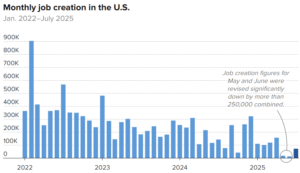

The U.S. job market has stumbled in a way that economists say could mark a turning point for the economy. July’s employment raised renewed alarm about a possible recession ahead as hiring has slowed to its weakest pace since 2020. After months of steady gains, job creation has all but stalled, with employers adding only 73,000 positions, well below the six-figure increase analysts had expected. More unsettling, earlier gains have proven to be far weaker than believed. May’s tally was slashed from 144,000 to 19,000, and June’s from 147,000 to just 14,000. Together, these revisions erased 258,000 jobs from the books, the largest two-month correction in nearly half a century outside the pandemic’s extremes.

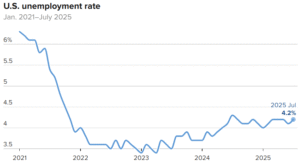

Meanwhile, the unemployment rate has ticked up to 4.24%, its highest level in over a year. Though still low by historical standards, the change hints that labor market conditions may not be as tight as previously thought. Over the past three months, job gains have averaged only 35,000 per month. Compare this to the roughly 128,000 per month added in the prior three months, and it’s clear that the hiring engine that powered the expansion through 2024 is starting to sputter. Analysts at JPMorgan noted in late July that the combination of sluggish current growth and steep downward revisions suggests a sharp decline in labor demand, indicating recessionary pressures may be building. While a single month’s data can’t confirm a downturn by itself, the trend matters. And the hiring trend is clear.

Cracks Beneath the Surface

Beyond the headline numbers, July’s report has exposed cracks in what had been a robust employment foundation. No, we’re not seeing mass layoffs—weekly unemployment claims remain relatively low, and companies are not yet slashing jobs en masse. However, the weakness in hiring is broad-based. Several sectors that had previously been sources of steady growth have gone cold or even begun shedding jobs:

- Manufacturing and Trade: Factories and wholesalers, which had been adding workers earlier in the year, showed net job losses in July. Slower demand and rising costs (in part due to tariffs on industrial inputs) have squeezed these sectors.

- Professional and Business Services: This white-collar sector lost 14,000 jobs in July, an unusual decline for a category that includes many office, consulting, and tech roles. Some analysts wonder if this is an early sign of efficiency moves, possibly even the impact of automation and AI quietly reducing the need for certain entry-level office jobs. The unemployment rate for college-educated workers jumped from 2.5% to 2.7%, hinting that new grads and white-collar employees are facing a tougher job market.

- Government: Federal government employment fell by another 12,000 positions in July and is down over 80,000 since January. Budget cuts and a drive to shrink the federal workforce have led to ongoing attrition—a trend likely to continue after recent court decisions cleared the way for further reductions.

- Healthcare (a lone bright spot): The healthcare and social assistance sector, a longtime workhorse of job growth, added about 73,000 positions in July, essentially accounting for all of the net gains nationwide. In other words, outside of healthcare, the rest of the economy created virtually no new jobs on net last month.

Overall, the share of industries increasing employment was only ~51%, meaning nearly half of all sectors actually cut jobs in July. That widespread cooling indicates the slowdown is not confined to one or two trouble spots; it’s more like a general draft that’s chilling many corners of the labor market. One modest consolation is that wages are still rising (albeit at a slower pace) and the average workweek held steady or lengthened slightly. Those metrics suggest that those with jobs are, for now, still seeing income growth. But if hiring remains this weak, experts say wage gains, too, may eventually falter as labor demand continues to cool.

Turning Point or False Alarm?

The breadth of the slowdown has fueled debate over whether the economy is approaching a turning point or simply enduring a temporary setback. Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook observed that July’s combination of a large miss and major revisions is “somewhat typical of turning points” in the economy. “We need to be cautious and humble,” she said, noting that averaging only ~35,000 jobs per month with back-to-back downward revisions is “concerning” and points to rising uncertainty.

History provides little comfort. Analysts at Morgan Stanley observed that the recent 258,000 downward revision to May–June payrolls is on par with revisions that have preceded past recessions. JPMorgan economists call the “slide in labor demand” a clear “recession warning signal,” warning that declines of this scale are “often a precursor to retrenchment.” In other words, a sudden halt in hiring is often the step just before companies start laying off people. Sharing a similar view, economists at Goldman Sachs described the labor market as approaching “stall speed,” where weakening becomes self-reinforcing and harder to escape.

Monthly U.S. job creation has fallen sharply, with Q2 2025 posting some of the weakest gains in years. May and June’s totals were later revised lower by more than 250,000 jobs combined. Image: CNBC

Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, said, “The risks are increasingly high that we’re going into recession.” While conceding, “We’re not there yet and maybe this thing gets turned around,” he warned that each passing week of weak data makes it “increasingly… hard” to avoid a downturn. In the immediate aftermath of the report, Zandi went further, declaring the economy “on the precipice of recession.”

Another prominent economist, Christopher Rupkey of FWDBONDS, sees the fingerprints of policy turmoil in the data. “The president’s unorthodox economic agenda and policies may be starting to make a dent in the labor market,” Rupkey observed, alluding to trade wars and other disruptions. “The door to a Fed rate cut in September just got opened a crack wider. The labor market is not rolling over, but it is badly wounded and may yet bring about a reversal in the U.S. economy’s fortunes,” he added.

Others remain cautious about drawing firm conclusions. Harry Holzer of Georgetown University argues it is “too early” to call a lasting trend, noting that a one-month miss, even with revisions, could be an outlier. Mark Blyth, political economist at Brown University, warns against confirmation bias: “People are anchoring on the jobs report and using it to telegraph a recession. I’m not sure it does that.” He added, “Nobody knows and everybody is doing wish fulfillment,” with political leanings often shaping interpretations.

Other analysts point out that key pillars of the economy remain intact, at least for now. There’s still no sign of the widespread job losses that typically characterize a recession. Consumer spending, which accounts for about two-thirds of economic activity, has been holding up, as households continue to spend on travel, dining out, and other services released from pandemic restrictions. Corporate earnings have generally come in better than expected, suggesting many businesses are still profitable and looking to grow.

As former Fed economist Claudia Sahm observed, “Recessions tend to be unforecastable… Often, there’s an event that causes people to lose confidence, change behavior, and start a downward spiral. Those events are very hard to predict.” In Sahm’s view, we may not tip into an actual recession unless some external shock or “trigger”, whether a financial crisis, geopolitical flare-up, or other surprise, pushes people and businesses into panic. Absent that, the economy might manage to trudge along at a slow pace (albeit a frustratingly slow one).

Even the more optimistic voices agree that the economy has weakened, just not enough to conclusively declare a recession inevitable. “A slow-growing economy is not a good economy,” Sahm added, tempering any complacency. “We want to avoid a recession, but avoiding a recession is a low bar. We want an economy that’s better than that.” The divide among experts highlights the uncertainty of the current economic landscape and a collective struggle to interpret ambiguous signals. Whether this marks the start of a prolonged downturn or just a temporary lull remains to be seen.

Policy Crosswinds and Uncertainty

Why has the jobs machine sputtered? A range of policy-driven crosswinds is buffeting the economy, creating an unpredictable backdrop that may discourage hiring. Chief among them is the ongoing trade war and tariff regime. In recent months, President Donald Trump has imposed wave after wave of tariffs on imports, covering everything from steel and aluminum to cars and consumer goods, as part of his “America First” economic agenda.

By August 2025, the effective U.S. tariff rate had climbed to its highest level since the 1930s. These duties act as a tax on globally connected businesses, lifting costs and prices. There are growing signs these tariffs are starting to bite: import-driven inflation has ticked up, raising the risk of a stagflationary mix of tepid growth and higher prices. Business investment has cooled as firms wait to see where trade policy will land. Uncertainty about the eventual trajectory of tariff levels has complicated long-term planning.

Federal Reserve officials have taken note of this “uncertainty tax.” Fed Governor Lisa Cook noted that many business leaders are spending an inordinate amount of time dealing with unpredictable costs and policy swings. By her estimate, CEOs and CFOs are devoting 20% to 45% of their time just managing uncertainty—adjusting supply chains, revising pricing, and hedging against policy changes. “There’s just uncertainty across the board,” Cook said, explaining how tariff oscillations and other shifting policies have forced companies into a defensive crouch. Susan Collins, President of the Boston Fed, agreed that firms have been in a “holding pattern” as tariff levels whipsaw up and down with ongoing negotiations. This environment naturally dampens hiring; few business leaders want to commit to new employees when they’re unsure what their input costs or export markets will look like next quarter.

The U.S. unemployment rate edged up to 4.2% in July 2025, its highest level in over a year, signaling potential softening in labor market conditions after a long period of stability. Image: CNBC

Trade isn’t the only headwind. The political drama around economic data and institutions themselves has added another layer of uncertainty. In a highly unusual move, President Trump reacted to the poor July jobs report by firing the Commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) the same day the data came out, after accusing the BLS of manipulating the jobs numbers. Former BLS officials condemned the action as “totally groundless” and a “dangerous precedent”. The episode raised concerns that politicizing statistical agencies could undermine trust in the data precisely when clear-eyed analysis is most needed. Some economists have privately expressed doubts about data quality following recent personnel changes at agencies such as the BLS. If businesses and households begin to question official numbers, confidence could erode further, discouraging investment and spending at a delicate moment.

Monetary policy is yet another factor in flux. The Federal Reserve had been raising interest rates in prior years to combat high inflation, but as the economy softened in 2025, the Fed hit pause. After the weak July jobs data, markets are now betting the Fed will cut rates as soon as September to provide some stimulus. Trump has loudly pressured the Fed for aggressive rate cuts, even lambasting Fed Chair Jerome Powell on social media – “Too Little, Too Late. Jerome ‘Too Late’ Powell is a disaster,” Trump complained on his Truth Social platform.

The central bank now finds itself at a potential inflection point: inflation has eased from its 2022 peak and is now much closer to the Fed’s 2% target, leaving the Fed room to lower borrowing costs if needed to shore up growth. However, Powell and his colleagues must balance that against not wanting to appear political or to re-spark inflation. The result is deep uncertainty over the future path of interest rates, trade policy, and even the credibility of economic data, all of which are central to business and consumer confidence.

Amid these cross-currents, some economists argue that the major drag on hiring now is essentially self-inflicted policy uncertainty. Economic historian Brad DeLong recently contended that today’s young job seekers face a tough climate primarily due to “widespread policy uncertainty and a sluggish economy, not the rapid rise of AI tools.” He notes that companies are postponing expansions and major projects amid unpredictable trade negotiations, shifting regulations, and political brinkmanship. “Uncertainty causes companies to delay major decisions, including hiring, in the face of an unpredictable policy environment,” DeLong said, adding that the on-again, off-again trade war has whipsawed many companies’ plans. Such risk-aversion often hits entry-level hiring first, and when firms pull back on growth plans, new job creation can quickly dry up.

Bracing for What Comes Next

The U.S. economy now stands at a fragile crossroads. Summer’s data has darkened the outlook, yet a recession is not inevitable. Whether July’s stumble is a passing setback or the first step toward a sharper downturn will hinge on the next few months. Growth has slowed, confidence is wavering, and while the line into contraction has not yet been crossed, the edge feels uncomfortably close.

The labor market will be the clearest gauge. If August and September bring similarly weak job creation and a steady rise in unemployment, economists warn that the case for an impending recession will grow stronger. Modest hiring gains, however, could still revive the “soft landing” scenario—the hope that the economy might cool without collapsing. Many forecasters, including some at the Fed, still cautiously hold this view.

Other indicators also deserve equal attention, including consumer spending, business investment, and credit conditions. So far, households have kept spending, but that resilience could crack under mounting anxiety or financial strain. The restart of student loan payments is already squeezing budgets, and a collective pullback in spending would likely trigger corporate cost-cutting measures, including layoffs. These pressures are one reason more Americans have been shifting savings into gold, a hedge they see as resistant to both inflation and financial market volatility. Gold buying tends to rise when trust in policy stability erodes, and the current mix of trade uncertainty, political turbulence, and shifting interest rate expectations has made it especially appealing.

The Federal Reserve’s next move will also shape the path ahead. With inflation falling from its 2022 peak, the Fed has room to cut rates. Markets now expect action as early as September. Lower borrowing costs could support mortgages, business loans, and credit lines, but policy changes take time to filter through the economy. Cut too slowly, and the downturn could gather speed; cut too quickly, and the Fed risks reigniting inflation or unsettling markets. For investors wary of such policy whiplash, gold offers a form of insurance not tied to central bank maneuvering.

It’s worth remembering that a two-quarter decline in GDP is not the official definition of a recession. The NBER looks for a “significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months.” By that measure, the U.S. is not there yet. Output, incomes, and revenues have not shown a sustained, broad contraction. Industrial production and consumer outlays remain mixed. That leaves open the possibility that the slowdown could level off before turning into a full downturn.

Still, prudence is in order. July’s weak report underscored how quickly momentum can fade. Families, businesses, and policymakers may benefit from preparing for multiple scenarios—bolstering emergency savings, diversifying investments, and strengthening balance sheets. For many, that preparation now includes increasing gold holdings as a shield against the dual risks of inflationary flare-ups and deeper economic weakness.

As Mark Blyth said, “Nobody knows” what comes next. Lisa Cook’s call to remain “cautious and humble” may be the most practical guidance available. The economy has a history of surprising forecasters, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse. After July’s jolt, Americans can only hope this is a stumble from which the economy regains its footing, but many are quietly hedging their bets.