By Preserve Gold Research

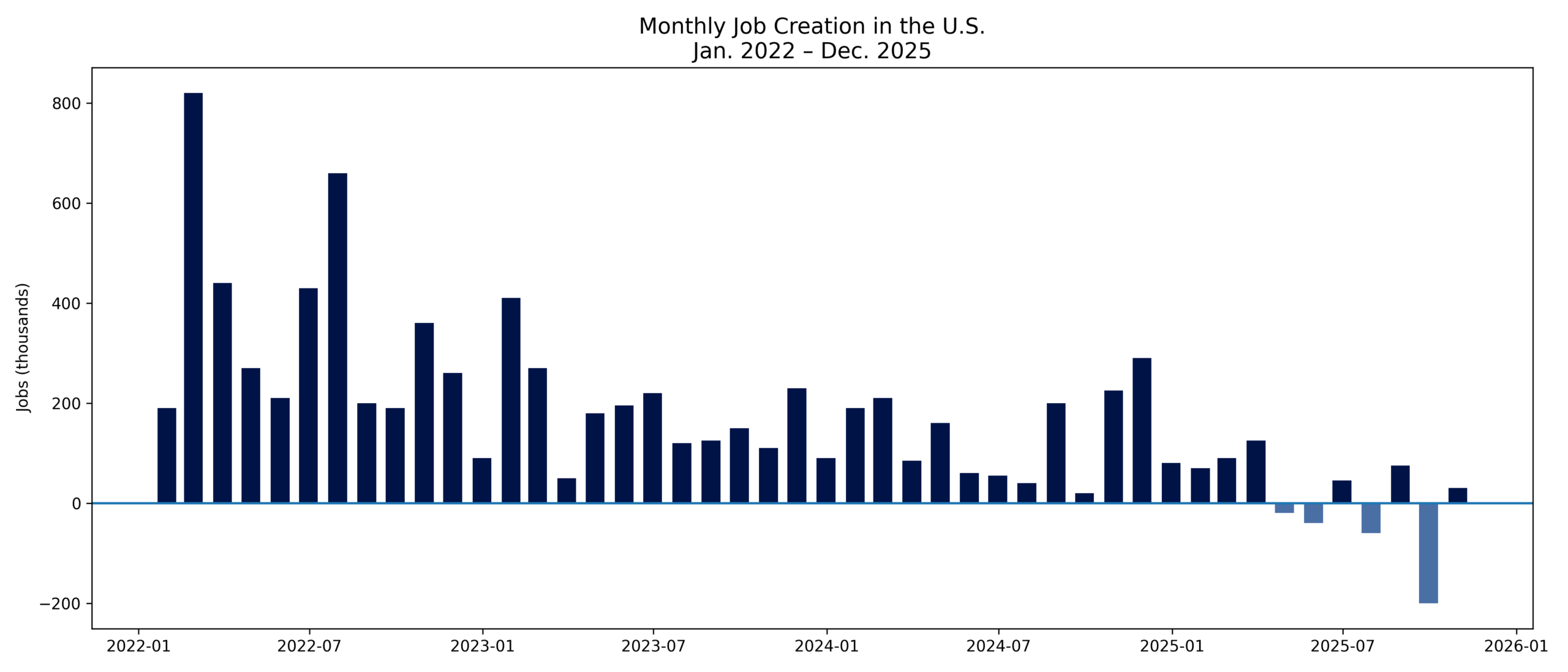

After a year of historically low unemployment, the U.S. labor market is no longer merely cooling. December’s employment report confirmed what economists have been saying for months: hiring has slowed to a pace inconsistent with a healthy expansion.

Nonfarm payrolls rose by just 50,000 in December, following a downwardly revised gain of 56,000 in November. That rate of job creation falls well short of what is needed to absorb population growth, let alone sustain economic momentum. Rather than a smooth deceleration, the data suggest an abrupt shift unfolding beneath reassuring headline figures.

In November 2024, the unemployment rate stood at 4.2%. By November 2025, it had climbed to 4.6%, the highest level in four years. December’s report did little to dispel the sense that the labor market has entered what economists describe as a low-hire, low-fire phase.

“The low-fire, low-hire jobs market remains intact as the unemployment rate continues to climb,” said Joe Brusuelas, who has warned that slowing hiring and cooling wage growth risk turning 2025 into a lost year for economic growth. The danger is not collapse but stagnation—an economy that drifts rather than advances.

What makes this slowdown unusual is the absence of a clear trigger. There has been no financial crisis, no surge in layoffs, no sudden retrenchment in consumer spending. Instead, employers have simply stopped adding workers. Positions go unfilled. Expansion plans are deferred. Hiring freezes quietly replace growth strategies.

For years, unemployment hovered between 3.5% and 4%, reflecting an unusually tight labor market. The move into the mid-4% range marks a meaningful break from those conditions. “Hiring is still stuck in stall speed, and job growth in the cyclical parts of the economy isn’t sending a comforting signal,” said Olu Sonola, cautioning that even temporary improvements in the jobless rate would not erase the broader weakness in job creation.

Across manufacturing floors and transportation hubs, sectors once expected to anchor employment growth have stalled. Job gains are increasingly concentrated in narrow corners of the economy, a sign that internal labor-market dynamics are shifting even as top-line indicators such as GDP continue to flash green.

Distorted Data, Real Damage

The dissonance in recent employment reports reflects not only economic strain but also statistical disruption. A federal government shutdown in October interrupted data collection, forcing the Bureau of Labor Statistics to cancel that month’s jobs report and compress multiple reporting cycles into November and December.

By the agency’s own admission, November’s survey was conducted under unusual strain. While December’s data were more complete, policymakers are now interpreting a sequence of reports never designed to carry this much analytical weight. Still, data quirks alone don’t explain the trend. Some furloughed federal workers may have been temporarily counted as unemployed despite later receiving back pay. But even after accounting for such anomalies, the direction is unmistakable. Labor conditions were weakening well before the shutdown.

Private-sector indicators captured the slowdown early. During the October blackout, economists turned to third-party employment gauges that showed essentially no job growth as early as September. “The job market is weak and getting weaker,” said Mark Zandi, warning that policymakers were “flying blind” at a critical moment.

Subsequent revisions only reinforced that view. Updated figures revealed that the economy lost 173,000 jobs in October. Payroll gains for August and September were revised down by a combined 33,000. November’s gain fell to 56,000. Taken together, these revisions point to fading labor demand that predates the shutdown and has persisted since.

The Emergence of a “Jobs Recession”

When job creation fails to keep pace with population growth, an economy may not look recessionary on paper, but it’s effectively standing still. By the second half of 2025, the U.S. labor market edged uncomfortably close to that threshold. Several months recorded outright job losses. Others posted gains too modest to restore momentum. Over a six-month span, employment contracted in multiple months, a pattern rarely seen outside formal recessions.

What hiring did occur was overwhelmingly concentrated in health care and social assistance. In November, roughly 46,000 of the 56,000 jobs added came from that sector alone. From April through November, total job creation amounted to about 119,000, while health care added more than 430,000 positions. Every other sector combined shed roughly 310,000 jobs. Strip out health care and education, Mr. Zandi noted, and job growth nearly disappears.

U.S. job creation has cooled sharply from its post-pandemic surge, with repeated downward revisions signaling a labor market losing momentum. As growth weakens and policy risks rise, the case for hard-asset protection strengthens. | Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED

Elsewhere, traditional engines of labor demand have stalled. Manufacturing employment contracted modestly in October and November, with losses spread across durable goods. Transportation and warehousing shed 18,000 jobs in November and nearly 80,000 since its peak. Leisure and hospitality, once a post-pandemic standout, has flattened.

As these weaknesses broaden, economists’ language has shifted. Some now openly discuss a jobs recession, a sustained period of employment contraction, even if GDP has yet to meet formal recession criteria. Moody’s Analytics places the probability of a recession at roughly 40% over the next year, citing the labor market’s sudden stall.

GDP Growth Without Jobs Is a Fragile Illusion

Paradoxically, even as hiring has dried up, other indicators remain superficially positive. GDP continues to grow in real terms, avoiding the two consecutive quarters of contraction that traditionally define a recession. Consumer spending and corporate output haven’t collapsed—yet at least. But the disconnect between a weakening labor market and positive GDP raises a fundamental question: can growth persist without job creation?

History suggests it cannot. Consumption accounts for roughly two-thirds of the U.S. GDP, and consumption ultimately depends on employment. Asset markets or productivity gains can temporarily buoy growth, but they aren’t durable substitutes for rising payrolls.

Wage growth is already slowing. Average hourly earnings are up 3.5% over the past year, the weakest pace since 2021. While slower wage gains may ease inflation pressures, they also erode purchasing power. Workers with stagnant pay spend less, reinforcing the hiring slowdown. Productivity gains have helped firms extract more output from fewer workers, supporting profits in the short run. But sustained under-staffing risks burnout, quality erosion, and weaker service, hardly a foundation for long-term growth.

What makes the moment particularly fragile is how little it would take to tip the balance. A pullback in business investment or a shock to consumer confidence could quickly expose the economy’s vulnerability once job creation has stalled. Zandi points to the downside risks accumulating beneath the surface: anemic hiring, softening demand, and policy uncertainty. If the labor market fails to regain traction, GDP is likely to follow it down. Either the job engine reignites, or today’s hidden weakness will drag the broader economy into its undertow.

Rate Cuts Can’t Fix Hiring Hesitation

The Federal Reserve has responded by easing policy. In mid-December, it delivered a third consecutive rate cut, bringing the benchmark rate into the 3.5% range. Lower rates typically spur borrowing, investment, and hiring. This time, the response has been muted. Employers aren’t holding back because credit is expensive; they’re hesitating for reasons that rate cuts alone can’t resolve.

Policy uncertainty looms large. From trade tariffs to immigration rules, businesses face unpredictable headwinds that complicate long-term planning. Trade policy has been a particularly acute factor as the wave of new import tariffs introduced earlier in 2025 has raised costs and destabilized supply chains. By some estimates, the effective U.S. tariff rate now stands at a multi-decade high. Industries exposed to these tariffs have responded by freezing hiring or trimming payrolls, citing margin pressure and uncertainty about future input costs. Federal Reserve Beige Book reports echo this caution, noting widespread hesitation to hire amid weaker demand and unclear conditions. Research from the Atlanta Fed suggests that policy uncertainty has reduced new hiring by roughly 13% and capital investment by about 16% as firms defer expansion.

Global risks compound the problem. Geopolitical tensions and slowing global growth create an environment in which businesses are reluctant to hire new workers. Manufacturers may delay a new plant if export markets look fragile. Logistics businesses may hold back if shipping volumes soften. These concerns are not easily offset by modest rate cuts. Faced with uncertainty, many firms are locking down spending, including labor costs.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has acknowledged that rate cuts are no cure-all. After the latest move, he warned that the labor market faces “significant downside risks,” pointing to surveys showing weakening demand for workers. He also suggested that payroll figures may overstate strength because of slower population growth tied to tighter immigration policies, a structural constraint beyond the reach of monetary policy. Subsequent data seemed to validate those concerns. A preliminary BLS benchmark revision revealed that 911,000 fewer jobs were created in the year through March 2025 than previously reported, nearly a full year’s worth of growth erased.

What This Means for Workers and the Broader Economy

For American workers, the slowdown is no longer abstract. Labor market stress rarely spreads evenly, and early signs of strain are becoming more visible beneath the headline numbers. Unemployment has been rising most sharply at the margins of the workforce, where job security is weakest, and income volatility is highest. While the overall unemployment rate eased to 4.4% in December, that figure masks growing pockets of pressure that tend to surface first when hiring slows. As Bill Adams of Comerica Bank notes, these early increases often serve as a leading indicator of broader labor-market stress.

Below the averages, the distribution of pain is widening. Higher-income and more secure workers have remained relatively insulated so far, while those concentrated in cyclical and service-oriented roles are beginning to feel the squeeze. Retail, hospitality, and temporary positions are seeing reduced hours as firms look to preserve margins without resorting to outright layoffs. The number of people working part-time for economic reasons rose by roughly 900,000 between September and November, as employers cut schedules rather than headcount. Short-term unemployment increased by more than 300,000 over the same period, signaling that job separations began to accelerate late in the fall. These shifts rarely dominate headlines, but together they point to a labor market fraying at the edges well before any formal recession call.

One mitigating factor remains. Initial unemployment claims are still low by historical standards, suggesting that mass layoffs have not yet materialized. That has limited immediate damage. It also leaves room for conditions to worsen if hiring freezes harden into cuts. A labor market that stops adding jobs doesn’t remain in that state indefinitely.

The labor market’s slide is an omen for the broader economy. Employment is often considered a lagging indicator, typically weakening after growth slows. In this cycle, however, it may be offering an unusually early warning. If so, late 2025 could come to be seen as the period when the economy quietly peaked and began to slip. Officially, the U.S. has not entered a recession. But for workers facing reduced hours, stagnant pay, or rising unemployment, the distinction feels academic. Either the job engine reignites soon, or the under-the-surface weakness now evident in the labor market will pull the broader economy into its undertow.