By Preserve Gold Research

If your grocery bill feels a little heavier and your paycheck feels a little lighter, you are not imagining it. Prices are rising again, and at the same time, the Federal Reserve has decided to cut interest rates. In August 2025, inflation quickened to its fastest pace in months even as hiring slowed to a crawl. Economists say that a split could pull the economy in opposite directions, leaving policymakers uncertain about which risk to contain first.

“Near-term risks to inflation are tilted to the upside and risks to employment to the downside – a challenging situation,“ Powell said following the Federal Open Market Committee’s September meeting. “Two-sided risks mean that there is no risk-free path.” Lower borrowing costs may bring brief relief on mortgages, autos, and cards. But a fresh burst of inflation could send the Fed scrambling to tighten credit if it continues to expand beyond the central bank’s 2% target. Consumers are already on the treadmill, and the margin for error for the Fed is razor-thin.

August 2025: Inflation at an Eight-Month High

After a year of cooling, inflation is edging higher again. The Consumer Price Index rose 2.9% year-over-year in August, the fastest pace since January. On a monthly basis, prices increased 0.4% from July to August, double the prior month’s gain and the largest one-month jump since the start of the year. Earlier in the spring, annual inflation sat near 2.3%, close to the Federal Reserve’s goal. But by August, the trend had turned, with inflation sitting comfortably above the target.

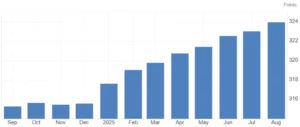

United States Consumer Price Index (CPI)

U.S. CPI rose to 323.98 in August from 323.05 in July. Year-over-year inflation quickened to 2.9 percent, the fastest since January, after 2.7 percent in June and July | Source: Trading Economics

Several everyday essentials drove the surge in August prices. Shelter costs increased 0.4% in a single month. Food rose 0.5%, with groceries up 0.6%. Energy ticked 0.7% higher, and gasoline jumped 1.9%. These gains suggest that inflationary pressures are no longer isolated to a few volatile categories as price increases are spreading across the economy. Core inflation (excluding food and energy) rose 0.3% month-over-month and 3.1% year-over-year, indicating that underlying price growth remains sticky across many sectors.

Americans have been feeling the squeeze from the supermarket to the pump to their rent checks. Credit card balances reached about $1.21 trillion in the second quarter of 2025, up $27 billion from the prior quarter and roughly in line with last year’s record. The total rose 2.3% in just three months. Delinquency remains elevated, with approximately 6.93% of balances transitioning to delinquency over the past year. According to a recent poll, two-thirds of Americans reported that prices have been rising in recent weeks and expect inflation to continue. At the same time, over half believe the economy is deteriorating rather than improving. After a hopeful lull, consumers now appear to be bracing for another round of higher living expenses.

Fed Says Risks Have Tilted Toward Slower Growth

On September 17, 2025, the Federal Reserve cut rates for the first time this year, lowering the federal funds target to 4.00-4.25%. That move would typically occur after a clear disinflation trend, when a path to the target inflation rate is established. However, the trend suggests otherwise. Headline inflation still sits nearly a whole point above target, and price pressure persists across core categories that impact daily life.

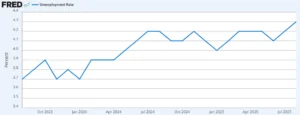

So why ease now? The answer lies in an increasingly soft job market and the Fed’s dual mandate to strike a balance between price stability and employment. From June through August, employers added an average of about 29,000 jobs per month, far below the roughly 106,000 pace seen in 2024. The unemployment rate, which had hovered near multi-decade lows, ticked up in recent months above 4%. While joblessness remains comparatively low, the trend is no longer improving. Initial claims for unemployment benefits also inched higher over the summer. Meanwhile, growth has shown signs of cooling, and job openings have declined, indicating that both workers and employers are becoming more cautious.

For the Fed, that tilt in risks matters. A weaker job market can pull down spending, undercut confidence, and slow growth further. In its official statement, the Federal Open Market Committee noted that “job gains have slowed, and the unemployment rate has edged up” even as “inflation has moved up and remains somewhat elevated.” Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues judged support appropriate “in light of the shift in the balance of risks” toward slower growth. In other words, economic growth and hiring have downshifted so much that the risk of a weakening labor market now looms larger, in the Fed’s view, than the risk of inflation running too hot.

Jobless rate creeps up through 2024–2025, settling near 4.3% in August | Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Policymakers have also suggested the recent inflation pickup may be temporary or manageable. Energy costs could cool, and softer demand could restrict pricing power and wage bargaining. If those forces take hold, inflation could ease without heavy tightening. While that scenario may play out, it relies on assumptions that some have questioned. Overly optimistic expectations often crumble under the weight of reality when it sets in.

The Fed is effectively threading the needle between two opposing problems: inflation that is above target and an economy that’s losing momentum. By cutting rates, the Fed aims to support employment and avert a harder landing. At the same time, officials must ensure they don’t inadvertently unleash higher inflation by easing policy too much. The line between help and harm couldn’t be much thinner.

“The committee tries to get a complete picture of the biggest downside risks…and then…weigh[s] these two conflicting objectives – it’s an art as much as science,” observed Villanova economics professor Erasmus Kersting, describing the Fed’s challenge. However, while markets can tolerate uncertainty for a while, households have more pressing needs. And patience may prove short if prices and borrowing costs both refuse to cooperate.

Will Prices Continue to Rise?

Experts say the Fed’s gamble could be fueling tomorrow’s inflation. With cheaper debt, consumers and businesses might borrow and spend more, which, if goods remain in short supply, can push prices higher. As analyst Parker Sheppard cautioned, the Fed must avoid the mistakes of the past, where policymakers “cut interest rates too soon, allowing inflation to become more deeply entrenched.” But with the Fed’s September cut, it may be too late. Should inflation continue to accelerate, the consequences could metastasize throughout the economy.

If prices continue to climb at an elevated pace, paychecks will buy less. Inflation chips away at real wages, shrinking what a dollar can secure at the store, the pump, and the landlord’s office. Since 1970, the dollar has lost about 88% of its purchasing power, and all signs point to this trend continuing. For households on fixed incomes, a renewed surge in prices could translate into a tangible drop in living standards – a quiet pay cut delivered through higher grocery, rent, and utility costs. Confidence might falter as people watch nominal gains disappear into the cost of living.

The strain at the checkout line tells one story. A more troubling scenario could be an economy that cools while costs continue to rise. Typically, a cooling economy moderates prices; however, the United States now faces weaker hiring alongside elevated inflation. If rate cuts fail to revive momentum, or if oil and other supply constraints continue to put pressure on prices, the country could drift toward a 1970s-style trap, characterized by flat or negative growth while costs continue to rise. History shows how painful that mix can be for families and how challenging it is for policymakers to unwind.

If that grind persists, psychology could take over, turning a difficult cycle into a self-reinforcing one. The Fed fears a loss of public confidence more than any single monthly print. If firms and households start to expect persistent inflation, they may act accordingly. Companies could lift prices in advance. Workers could press for larger wage gains. A stop-and-go stance in the past has encouraged expectations of higher future inflation, and recent surveys already show that many Americans are bracing for more price increases. If the September cut appears to be wavering on the 2% goal, credibility could suffer, and bringing inflation back down could become much more challenging.

At this point, Fed officials have emphasized that they are not abandoning the fight against inflation – they are trying to pursue a nuanced strategy of supporting growth while keeping a close eye on prices. But if price increases keep hitting new highs into late 2025, the central bank will face immense pressure to rethink its stance. In that case, the “soft landing” goal (cooling inflation without a recession) would become far more elusive.

Stop-Go Lessons That Still Haunt Policy

Economic history casts a long shadow over the present debate. Veterans of the 1970s and early 1980s recall how stubborn inflation can grind down households and how policy errors can deepen the damage. The Fed of that era eased too soon when unemployment rose; inflation then returned, louder and meaner. Under Fed Chair Arthur Burns, a stop-go pattern took hold. Officials would tighten, then reverse when labor markets weakened, and the credibility needed to subdue prices slipped away.

For example, in 1973, the Fed raised rates as inflation spiked, then eased before price pressures truly cooled. Inflation dipped in 1976, only to swell back to double digits by decade’s end. Businesses started to expect persistent price increases and built those assumptions into wages and list prices. Each attempt to stimulate growth risked confirming the fear that inflation could worsen. Too often it did.

The bill for those choices arrived as the Great Inflation, a period of high prices and volatile growth that rattled the U.S. economy. By 1979, consumer inflation reached 9%. It fell to Paul Volcker, appointed Fed Chair in 1979, to finally break the cycle. Volcker did so with brute-force measures. He raised interest rates and tightened monetary policy aggressively, signaling that restoring price stability would take precedence over short-term growth.

The price was steep – the early 1980s recession was among the worst since the Great Depression, with unemployment topping 10%. But that painful episode is credited with crushing the back of inflation and restoring the Fed’s credibility. “What distinguishes Volcker from Burns,” noted one analysis, is that Volcker “followed through” on inflation-fighting and resisted political pressure to ease at the first sign of pain. He understood that consistent, tough policy was needed to re-anchor expectations. Even as farmers drove tractors in protest outside the Fed’s headquarters and Congress howled about the soaring cost of credit, Volcker soldiered on.

Today’s officials are well aware of this record. Chair Jerome Powell has often expressed admiration for Volcker’s resolve, indicating he does not want to repeat the stop-go errors of the 1970s. Even so, hints of that pattern appeared in late 2024 when the Fed cut rates several times while inflation sat above target. Critics at the time argued that the Fed should have held firm longer. “Inflation remains stubbornly above 2%, yet the Fed [cut rates]…The costs of prematurely stopping the anti-inflation campaign are clear,” one commentary warned in December 2024, citing risks from higher inflation and lost credibility. Today, those words echo loudly as the Fed embarks on another easing cycle with inflation reaccelerating.

Historical case studies reinforce that once inflation expectations lose their anchor, the cure is far more painful than prevention. During the 1974-1975 recession, the Fed thought it had inflation licked and shifted to stimulus because the economy was in free fall. Initial data even suggested inflation was coming down. But those reports proved wrong. Inflation wasn’t truly defeated, and when the Fed eased under political pressure, inflation rebounded later in the 1970s. The lesson? False dawns in the data can mislead policymakers, and acting on incomplete information can worsen the long-term outcome.

Similarly, in 1980, the Fed (briefly under Chairman G. William Miller) cut rates as a recession hit while inflation was still over 10%. Inflation abated only temporarily, then surged again, forcing Volcker’s drastic intervention. By late 1980, as noted, interest rates had to be ratcheted up to ~20% and the economy was crushed under the weight of credit costs. Only then did inflation finally peak (at 11.6% in March 1980) and begin its downward trajectory.

The lesson for the current Fed may be simple to say, yet difficult to execute. Inflation today sits far below the peaks of the 1970s, but expectations could still drift if policy becomes too generous while price pressures linger. If inflation accelerates from here, officials may need to harden their stance to prevent an upward spiral. Credibility, once lost, could take years to rebuild. The ghosts of the 1970s suggest that a central bank that flinches might buy calm now at the price of deeper pain later. Any misstep could reopen the very fight the country hoped it had finished.

September’s Lone Half-Point Vote Signals a New Fault Line

One change at the Fed could matter over the coming months. The Senate recently confirmed Stephen Miran to the Board of Governors, in a 48–47 vote. Miran, a Trump loyalist, has argued that current rates sit above a lower neutral level and could be restraining hiring more than necessary. In speeches and interviews, he has pressed for faster, deeper cuts, at times pointing to non-monetary forces, such as tariffs, as reasons why policy might need to offset growth drags. His push for policy near the mid-2s contrasts with Chair Powell’s slower approach, which emphasizes finishing the job on inflation before easing more. Of the twelve members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Miran was the only one to vote in favor of a larger, half-percentage point cut in September.

Most members, like Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee, have publicly stated their preference for a more moderate approach. “Heavy front-loading of cuts before you know whether this is all there’s going to be on inflation and before you know whether this inflation is going to be persistent runs a risk of a mistake,” Goolsbee said in a recent interview. His view has been echoed by other members, including Kansas City Fed President Jeffrey Schmid, who has warned that “inflation remains too high” for the Fed to take any chances. The divergence between Miran’s outlook and that of other policymakers could mean the Fed will have to tread carefully in its communication about tapering.

Policy Signals Blur, Households Seek a Safer Anchor

Late 2025 finds the U.S. economy at a critical juncture, where prices remain elevated while the risk of a recession looms large. In the months ahead, the difference between success and setback could be small. By early 2026, we may see whether September’s decision supported stable growth or invited a new chapter of price inflation. However, one thing is sure: with pandemic scars, geopolitical shocks, and uneven supply responses blurring the signals policymakers rely on, the path ahead remains highly uncertain.

When the signposts blur, households may want ballast. Diversifying savings with gold could add a store of value that’s not dependent on a single policy outcome. Gold may not promise exponential gains, but it often holds its purchasing power when paper assets wobble. In periods when inflation runs hotter than expected, gold often responds favorably to rising uncertainty, shifting real rates, and safe-haven demand. That blend could help cushion savings when prices climb and confidence weakens.

Inflation hedging works through channels that investors can track. Real interest rates matter, since lower or falling real yields often lift the opportunity cost of holding cash more than the cost of holding gold. Currency moves matter as well, especially a softer dollar that can bolster bullion prices. Market stress matters most. When investors start to doubt the path of policy or the durability of growth, gold may act like insurance, absorbing the fear that leaks out of stocks and credit.

History offers a cautious guide. Gold has not perfectly tracked the consumer price index month by month, but across long stretches of negative real rates and elevated geopolitical risk, it has often protected purchasing power. In a late 2025 backdrop of sticky prices and fragile growth, that asymmetric profile could be valuable. While it may not eliminate risk, it could spread it across engines that are not prone to fail all at once.