By Preserve Gold Research

At first glance, June’s employment report signaled a resilient labor market. Employers added 147,000 payroll jobs while the headline unemployment rate ticked down to 4.1%, beating most economists’ expectations. “We got an absolutely solid payroll number,” remarked RSM chief economist Joe Brusuelas. “You’re just not seeing any feed through from tariff or trade-related stress.” However, a deeper look at the data reveals several troubling undercurrents. From the types of jobs being created to the hours people are working, June’s report holds clues about the health of the labor market. These less-publicized details paint a more nuanced picture of the job market, one that might indicate mounting vulnerabilities despite the upbeat headlines.

Government Jobs Propping Up Growth

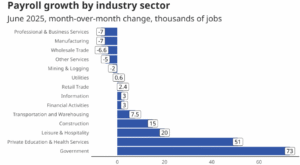

Arguably, the most concerning detail in June’s employment report is the outsized role of government hiring. Fully half of June’s net job gains came from the public sector, supplying 73,000 of the 147,000 positions logged. This surge in government employment was the largest monthly jump in over a year, and it helped mask what was otherwise a tepid month for private employers. With only 74,000 jobs added across the entire business sector, private hiring has slipped to a nine-month low.

June’s tilt toward government payrolls may be less a fleeting quirk than the latest sign of a deepening trend. It continues a pattern that has hardened in recent years, with federal, state, and local agencies absorbing a growing share of job seekers. Throughout 2024, a disproportionate slice of new positions already came from government offices, and the latest numbers point to a revival of that dynamic. Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that June was among the five most government-dependent months for employment growth in the past decade, a level of government-driven employment rarely seen outside of recessions or recovery from crises.

Why does this matter? For one, government employment is ultimately funded by taxpayers (or government borrowing), not organic private-sector demand. A job market where public jobs carry the weight can give a false impression of economic vitality. The concern is that such growth may not be sustainable, especially if it’s buoyed by expansive fiscal policy. State and local governments have been on a hiring spree (80,000 jobs in June), often backed by federal funds. This raises questions about how long the public sector can keep driving employment gains if budget pressures mount. It’s telling that while state and local governments added jobs, the federal government shed 7,000 positions in June as part of belt-tightening efforts, even as overall government employment rose.

Nearly all net job growth came from state/local government and health-related sectors, while key private industries like manufacturing and professional services lost jobs (negative bars indicate job losses). Source: Hiring Lab

Economists suggest that a jobs report propped up by government hiring is not sustainable in the long term. “The gains will likely ring hollow“ for many job seekers, warned Hiring Lab economist Corey Stahle, because hiring outside a handful of areas, chiefly government and health care, appears “anemic at best.” There is also a broader economic implication as government payrolls contribute to GDP. A spike in government jobs can temporarily inflate output statistics, but that doesn’t necessarily indicate improved productivity or private-sector vitality; it may simply reflect fiscal stimulus. With almost every second new employee joining a taxpayer-funded payroll in June, the labor market “may be a tent increasingly held up by fewer poles,” Stahle added. If the main pole is government hiring, one must wonder what could happen should that support weaken.

Manufacturing and Other Goods Sectors Slump

Manufacturing was once billed as the engine of a fresh American boom, yet recent numbers paint a very different scene. Factory payrolls shrank again in June, marking the second monthly drop in a row and the eighth flat or negative reading in the past year. Only two months since last summer have shown factory gains above a thousand positions, a glaring gap between political promises and shop-floor reality.

The broader goods-producing arena looks no healthier. Goods industries scraped together a net gain of roughly six thousand jobs in June, and construction accounted for every bit of that growth. Strip out the fifteen-thousand jump at building sites, and the entire goods sector would have bled positions. Construction remains the lone bright spot, propped up by infrastructure projects and earlier strength in housing. Factories, on the other hand, have faced higher borrowing costs, weaker demand for big-ticket items, and lingering trade uncertainty. Those pressures have nudged employers to slow hiring or turn to layoffs, hardly proof of a booming economy on Main Street.

History adds an extra layer of worry. Manufacturing often rolls over before a broader slump, just as it did ahead of the mini-recession in late 2019 and in the run-up to the 2007 downturn. A similar pattern may be unfolding today. Wholesale trade offers another warning: payrolls there fell by more than six thousand in June, hinting that retailers and producers could be trimming orders.

Goods-sector weakness also delivers a social punch. Plants and mines usually pay premium wages to workers without college degrees. When those jobs vanish, working-class communities lose a vital lifeline. Despite repeated vows to reshore production, the latest data show a factory labor market that has plateaued and may be sliding into contraction. If that descent continues, the economy’s foundation could prove shakier than optimistic headlines suggest.

Fewer Hours Worked and Other Red Flags

Apart from manufacturing jobs, other indicators point to potential economic struggles for working-class households. In June, the average American worker saw their hours tick down, a subtle but significant indicator. The average number of hours worked per week dipped by 0.1 hour in June, marking the first decline in this metric in over a year. That may sound minor, but stretched across an entire workforce, it suggests employers have started to scale back labor usage.

Companies often shorten shifts before they cut headcount, so shrinking hours may foreshadow layoffs if demand fails to rebound. Fewer hours also mean smaller paychecks for hourly workers, which can soften consumer spending. This is one of those under-the-hood details that barely gets a mention in headlines but carries weight as an early warning sign. The dip in hours joined a list of other labor market indicators that flashed yellow in the June report:

- Labor force shrinkage: The labor force (people working or actively seeking work) fell by roughly 700,000 in June, nudging the labor force participation rate down to 62.3%. While still up compared to a year ago, this reversal is not a welcome development. A declining participation rate means a smaller share of Americans are engaged in the job market.

- Rising discouraged workers: There was a 70% surge in “discouraged workers,” or individuals who left the job search, because they believed no work was available. Such a large jump in one month may partly reflect statistical noise, but it aligns with the story of a cooling job market in which more people are giving up looking.

- Uptick in certain unemployment rates: Unemployment rates for some groups actually rose in June. Teenage unemployment jumped (a sharp increase that analysts tied to factors like tariff-related uncertainty hitting summer jobs, and minimum wage changes). Unemployment among Black workers also climbed somewhat. These increases suggest that the benefits of the recovery are not reaching all groups evenly, and that the most vulnerable workers are starting to feel the downturn first.

- Longer jobless spells: The duration of unemployment for those jobless is growing. The average time unemployed ticked up from about 21.8 weeks to 23 weeks, and the share of people unemployed long-term (15 weeks or more) rose as well. In plain terms, once people lose jobs, they are finding it harder to get back into employment quickly, a classic late-cycle sign as hiring cools.

- Stalled full-time transition: There are signs that those stuck in part-time jobs can’t easily find full-time positions. Slack business conditions were cited as preventing part-timers who want full-time work from making that transition. In a robust job market, employers compete for labor and tend to convert part-timers to full-time or increase hours; the fact that this isn’t happening suggests businesses are cautious.

These red flags paint a picture of an economy where the low-hanging fruit of the recovery has been picked, and deeper structural pains are emerging. For instance, analysts suggest that the drop in labor force participation is due to a combination of retirements (as baby boomers age out) and discouragement. It’s true that prime-age participation (workers 25–54) remains relatively high, around 83.5%, though even that remains a bit below its late-2024 peak. But any decline in overall participation means fewer workers contributing to growth and potentially more people depending on others, which can strain economic dynamism.

The spike in discouraged workers is particularly alarming. A 70% increase in a single month suggests that many people lost hope in June’s job market. It’s possible that after months of hearing about a “hot labor market,” some job seekers found reality to be far different, especially outside the few hiring hotspots. If people stop looking for work, they no longer count as unemployed in official stats, which can deceptively push the unemployment rate down even as underlying joblessness or dissatisfaction rises. In June, the unemployment rate dipped to 4.1% partially reflecting such dynamics: some people left the labor force entirely, which can mathematically lower the jobless rate even though it’s not necessarily good news when people give up job hunting.

Another concern is the rise in long-term unemployment. When more people remain jobless for 15 weeks, 27 weeks, or longer, it becomes harder for them to re-enter the workforce at all. Skills can atrophy, and employers sometimes hesitate to hire someone with a long gap. The fact that the average unemployment spell lengthened is a sign that, beneath the churn of hiring and firing, a subset of Americans is stuck in unemployment longer. This often happens toward the end of economic expansions when job growth slows; openings get scarcer, and it takes longer for the unemployed to find a suitable position. It’s a metric to watch, because persistent long-term unemployment can become self-perpetuating and lead to people exiting the labor force for good.

Slowing Wage Growth Amid Sticky Inflation

Paychecks still grew in June, yet the pace looks increasingly sluggish. Average hourly earnings crept higher by 0.2% (about eight cents), and stood 3.7% above last year’s level. That rise kept workers slightly ahead of inflation, but it trails the brisk wage gains logged in 2022, when competition for labor felt intense. Slower pay growth suggests that firms feel less urgency to boost compensation, an attitude that aligns with a cooling job market. If employers no longer need to sweeten offers, households could find their spending power improving only marginally, another quiet sign that the economy’s pulse may be easing.

From workers’ perspective, the purchasing power of paychecks is improving only gradually. Inflation has been coming off the boil (the personal consumption expenditures price index was around 3.5% year-over-year in June), so 3.7% wage growth implies a small real gain for the average employee. That’s certainly better than the pay cuts after inflation that workers experienced in 2022’s inflation surge. Yet the fact that wage growth is slowing may indicate that the balance of power in the labor market is shifting back towards employers. For much of 2021–2022, businesses had to offer hefty raises, sign-on bonuses, and other incentives to fill positions, driving wage growth above 5%. Now, with the post-pandemic hiring frenzy abating and more people coming back to the workforce earlier in the year, pay raises have become more modest.

Economists often watch wage trends for hints about inflation and labor market slack. The June data’s combination of cooling wages and cooling hours worked fits the story of a job market that’s past its peak tightness. It relieves some fears of a wage-price spiral (where wage gains fuel inflation in a vicious cycle). But for workers, it’s a double-edged sword. While their pay is no longer being eroded by rising prices as badly as before, smaller raises mean household incomes won’t be growing rapidly either. Given that consumer spending drives about 70% of the economy, a slowdown in aggregate wage growth could translate to more tepid consumption in the coming months, especially if people feel uncertain and choose to save any incremental income.

Historical Parallels and Outlook

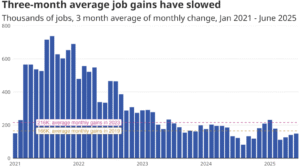

When virtually all the net job growth is concentrated in a few areas, in June’s case, the public sector and healthcare, it harkens back to late-cycle dynamics seen in previous economic expansions. As an expansion ages, hiring often narrows to defensive sectors. For instance, healthcare (a necessity people use in good times or bad) tends to keep adding jobs steadily, even when more cyclical industries falter. Government hiring can also act as a stabilizer (or a politically driven boost) late in a cycle. Meanwhile, interest-sensitive sectors like manufacturing or professional business services start to lose steam.

We’re seeing a similar pattern today: healthcare/social assistance added ~39,000 jobs in June, and state/local government added ~80,000, together accounting for 94% of June’s job gains. Historically, when job growth becomes this skewed, it can precede a broader slowdown. In 2007-2008, healthcare kept hiring right up until the recession deepened, while government employment initially stayed flat or grew (especially at the federal level with stimulus efforts), even as private payrolls began contracting.

Despite a modest uptick in early 2025, three-month average job gains remain far beneath the 2023 pace, suggesting the labor engine could be losing thrust just as the economy may need fresh momentum. Source: Hiring Lab

After the 2008 financial crisis, government jobs eventually fell too (especially at state/local levels due to budget cuts), but not before temporarily propping up employment in the early stages. The Great Recession was extreme, but the pattern of narrowing job growth also showed up in milder slowdowns, like the one in the mid-2010s energy sector slump (2015-16), where only a few industries like healthcare and services kept national numbers positive while mining and manufacturing jobs declined. The current moment echoes that late-cycle pattern: we have yet to see outright aggregate job losses, but the engine is running on only a couple of cylinders.

What does this mean looking forward? There are a few implications and possibilities, each with considerable uncertainty:

- Risk of Recession vs Slow Landing: The pervasive weaknesses under the surface suggest the economy could be edging toward a tipping point. Some economists warn that a recession becomes more likely when key sectors like manufacturing, transportation, and temp help are contracting—those are often precursors to broader job losses. If consumer spending were to pull back or if businesses retrench further, the narrow base of current job growth might not hold up, and we could see overall employment start to decline in coming months. On the other hand, the U.S. may experience a slower glide path where job growth continues but at a slower pace, and unemployment only inches up gradually. There are still foundational strengths like demographic labor shortages and employers reluctant to lay off workers, which might help prevent a sudden collapse in jobs.

- Federal Reserve and Interest Rates: One somewhat ironic result of the superficially “strong” June jobs number is the political cover it gives the Federal Reserve to keep interest rates elevated. Payrolls exceeded forecasts, unemployment slipped to 4.1%, and those surface cues allow Chair Jerome Powell to argue the economy may not require relief. Officials can point to the numbers and say growth persists, even though half of the new positions came from government offices. Because core inflation remains above the Fed’s target, policymakers might decide to wait, or even nudge rates higher, until clearer weakness appears. So, paradoxically, the hidden weaknesses might not stop the Fed from keeping monetary policy relatively tight, since the surface indicators provide plausible deniability to stay the course. It’s a delicate balancing act, and June’s report has given fodder to both hawks and doves: hawks see a resilient job market needing restraint, doves could point to falling participation and wage moderation as signs of cooling.

- Fiscal Sustainability: As discussed, federal relief funds to states, infrastructure projects, and other programs have kept public payrolls expanding. Yet, with the federal deficit soaring, there are open questions about sustainability. Political pressures may eventually curtail the ability or willingness of governments at various levels to keep adding jobs at this pace, especially if inflation worries persist or if there’s a shift toward austerity. If public hiring fades and the private sector doesn’t step up by then, overall job growth could sputter.

- Consumer and Business Confidence: These subtle job market weaknesses can also feed into confidence. If workers sense that hours are being cut or hiring is getting harder (as the discouraged worker jump suggests), they might turn more cautious on spending. Consumer sentiment often lags job news slightly, but it can shift if layoff news picks up or if wage growth doesn’t keep up with expectations. Business confidence could weaken as well. Many firms have shown a “hesitancy to hire“, as evidenced by an ADP report revealing private payrolls fell by 33,000 in June. The discrepancy between ADP’s data and the official numbers suggests that small and mid-sized businesses are pulling back, even as government and health giants boost the official totals. If businesses broadly grow wary, due to say, rising costs, credit tightness, or demand worries, they could freeze hiring or start layoffs, turning a slow bleed into a more rapid deterioration.

Looking ahead, the best-case scenario would be that these negative signals are a soft patch that the economy can power through. Manufacturing could stabilize if interest rates stop rising, and infrastructure and reshoring efforts could eventually create factory jobs. Job growth may continue, just at a slower (more “normal”) pace, bringing the labor market into better balance without a recession. Government and healthcare job growth might buy enough time for other industries to gather steam in this optimistic outcome.

However, the accumulation of evidence from June’s report leans more pessimistic. As one market analyst and investment advisor bluntly put it, “Don’t take the June jobs report at face value.” The data “isn’t as solid as it seems on the surface,” and we may be witnessing the early stages of a turning point in the labor market. June’s hidden bad news might be telling us that the economic expansion’s foundation is weakening, even if the facade hasn’t cracked just yet. And if there’s one lesson from past cycles, it’s that seemingly sturdy economies can weaken gradually, then all at once.