By Preserve Gold Research

America’s gross federal debt has climbed past $37 trillion, a figure so large it rivals the combined annual output of China, Germany, Japan, India, and the United Kingdom. Budget Chairman Jodey Arrington of Texas recently framed the jump in stark terms: “When my son was born in 2011, the national debt was $15 trillion. Now, 14 years later, it exceeds the GDP of the other five largest economies combined.” Such a vast amount is hard to grasp until it’s broken down into cost per person. As of August 2025, the gross federal debt works out to more than $108,000 for every man, woman, and child in America. The total now matches the nation’s entire yearly output, a ratio the country saw only briefly in the aftermath of World War II.

Unlike the post-war era, however, today’s high debt isn’t the aftermath of a singular victory or crisis; it’s the result of years of imbalance between spending and revenue. As Maya MacGuineas of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget warns, “spending and revenue are woefully out of balance, to the tune of nearly $2 trillion annually and rising.” The new $37 trillion mark should serve as a wake-up call, she argues, to the dire state of federal finances. If trends persist, fiscal pressures could intensify, growth may slow, and households might feel the squeeze through higher taxes, reduced services, or both. The longer the nation waits to address these challenges, the more difficult the tradeoffs may become.

A Record-High Debt Arrives Ahead of Schedule

Crossing the $37 trillion threshold was never supposed to happen this fast. In early 2020, the CBO expected that marker to sit safely beyond 2030. But the calendar moved up. A once-in-a-century pandemic collided with aggressive policy responses, and the borrowing meter spun at warp speed. Under both Presidents Trump and Biden, Washington opened the fiscal spigot to support the economy amid lockdowns, job losses, and public health demands. Trillions flowed into stimulus checks, enhanced unemployment, small-business lifelines, and medical infrastructure. Necessary in the moment, those choices piled debt onto an already fragile baseline, setting a new tempo for federal borrowing.

Even after the acute pandemic phase passed, debt continued to mount. In 2023, partisan showdowns over the debt ceiling temporarily cooled issuance, but it didn’t change the math. From January 2025 into August, the Treasury relied on so-called extraordinary measures, and the headline total hovered near $36.2 trillion. Then the dam opened. Lawmakers and the White House agreed to suspend the ceiling and authorized additional borrowing, with a budget reconciliation measure effectively lifting the cap by about $5 trillion. The Treasury promptly settled deferred obligations and financed fresh commitments, catapulting the gross debt past $37 trillion in early August 2025. The milestone arrived not because underlying pressures faded, but because Washington chose room over restraint, even as the warning lights burned brighter.

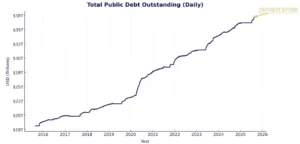

Outstanding U.S. debt hit $37.28 trillion on Aug. 27, 2025, nearly double its 2015 level, reflecting pandemic-era borrowing and rising interest costs pushing the total to new highs. Source: Treasury Gov

Policy decisions this year have only added fuel to the fire. After taking office, President Trump signed into law a package of tax cuts and spending increases, nicknamed the “One Big, Beautiful Bill“. Over the next decade, the plan is projected to add approximately $4.1 trillion to the ledger. While proponents argue that the tax cuts will spur growth and eventually pay for themselves, critics warn that pairing deep tax reductions with substantial new outlays will be a budget-busting combination. “We would have hit $37 trillion months ago if not for earlier accounting maneuvers to avoid the debt limit,” MacGuineas noted, referencing how extraordinary measures only delayed the inevitable. Now that those stopgaps are gone, the debt is free to surge—and surge it has.

By historical standards, the nation’s exponential debt growth is unnerving. Michael Peterson, CEO of the Peterson Foundation, observed that trillion-dollar debt milestones are now “piling up at a rapid rate”. The U.S. added $1 trillion in just the last 5 months. For context, the debt hit $34 trillion in January 2024, $35 trillion by July 2024, and $36 trillion in November 2024. Now, less than a year later, we’re above $37 trillion. That’s more than twice the average growth rate over the past 25 years. According to the Joint Economic Committee, if current trends continue, the next trillion dollars will be added in less than 170 days, less than six months from now. In other words, the pace of debt accumulation is accelerating, bringing us into uncharted territory much sooner than anyone expected.

Spending Sprees and Surging Deficits

Why is the debt climbing so fast? Because Washington continues to spend more than it collects, year after year. Deficits have been the norm for decades, yet recent shortfalls have swollen to levels not seen since World War II. Over the past twelve months, from August 2024 through July 2025, the federal government borrowed about $1.9 trillion to plug the gap. That sum equals roughly 6.5% of the entire economy, an unusually large deficit for a period without a deep recession or a global war.

Monthly Treasury reports from this summer show just how skewed the nation’s fiscal picture has become. In July 2025, the Treasury collected about $339 billion, a bit higher than the same month a year earlier. Outlays, however, surged to roughly $629 billion, the highest July on record. Put simply, Washington spent close to two dollars for every dollar of revenue. The result was a monthly hole of close to $291 billion. That shortfall was 19% larger than in July 2024 and marked the biggest July deficit in four years, surpassed only by the emergency-laden July of 2021.

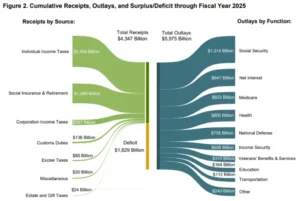

Although revenues in July 2025 were about $9 billion higher than a year earlier, spending has grown at a much faster pace. Across the last twelve months, the government collected about $5.2 trillion in taxes. Outlays, however, reached roughly $7.1 trillion over the same period. That arithmetic suggests persistent annual deficits in the $1.5 to $2 trillion range if no changes are made.

Through FY2025, the U.S. collected $4.35T but spent $5.98T led by Social Security ($1.31T) and net interest ($0.84T), resulting in a $1.63T deficit. Source: Treasury Gov

Which categories are doing the heavy lifting on the red ink? Interest payments on the existing debt itself now loom large and could grow as bonds roll over at higher rates. Demographics shifts and inflation have also pushed up mandatory costs for Social Security and Medicare. Defense and other discretionary spending have also increased, as the administration and Congress have shown little appetite for austerity. Even where cuts were promised, the overall impact on the budget has been negligible, with one economist bluntly calling the touted cuts a “nothingburger” in the grand scheme of multi-trillion-dollar spending. The government continues to live beyond its means and fills the gap by issuing more debt.

Compounding does the rest. If August and September look anything like July, analysts suggest the fiscal 2025 deficit could exceed $2 trillion. Outside of the 2020 crash, that would rank as the worst single year for red ink in modern history. By comparison, the fiscal 2023 deficit hovered near $1.7 trillion, which already seemed uncomfortably high. Warnings are mounting that such a budgetary trajectory is untenable, with experts from across the political spectrum urging action to avoid deeper economic fallout. So far, those warnings have not translated into a changed course; instead, policymakers have largely kicked the can down the road, choosing short-term political ease over difficult long-term choices.

Tariffs as a Debt Cure?

Amid a swelling sea of red ink, the White House has promoted an optimistic theory: hike tariffs, collect a windfall, and use it to pay down the debt. Rates on imports have risen sharply in 2025 as the administration has expanded coverage to dozens of trading partners, and receipts have been on the rise. By July, customs duties reportedly were 252% higher than they had been a year prior, thanks to the hikes. The Commerce Secretary, Howard Lutnick, bragged in a July interview that the U.S. was now collecting “close to $30 billion a month in tariffs.” He went so far as to claim, “This is going to pay off our deficit.” The President went further, suggesting tariff revenue will not only “pay down America’s $37 trillion debt…in very large quantity,” but might even be so bountiful that “we may very well make a dividend to the people of America” from the surplus. The pitch sounds tidy, but economists say the arithmetic doesn’t add up.

In recent interviews with Fortune, two prominent economists examined Trump’s tariff math and found it severely lacking. Joao Gomes, a finance professor at Wharton, noted that the extra tariff income might offset a portion of the costs of Trump’s “One Big, Beautiful Bill Act”, which the CBO projects will add roughly $3.4 trillion to the debt by 2034. However, tariffs will “leave the national debt picture similar.”

Desmond Lachman, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and former IMF official, was even more blunt. He said President Trump’s notion of raising $300 billion from tariffs (a generous estimate of annual tariff revenue if trade flows hold up) is just “a drop in the ocean” compared to a $37 trillion debt mountain. “The country is on a really dangerous debt trajectory,” Lachman warned, and tariffs don’t change that fundamental fact. While the White House has tried to frame the tariffs as a dual-purpose tool that could revitalize U.S. industries and fix the debt, investors aren’t buying it, according to Lachman. “Markets aren’t dumb. They can do the arithmetic and figure out that this is nonsense,” he said dryly.

The monthly cash flows make the problem plain. In July, interest on the existing debt ran about $61 billion. Tariffs brought in roughly $30 billion. Duties didn’t even cover half a single month’s interest, let alone touch the principal. And July was a relatively high point for tariff collection; if a global slowdown or retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports occur, experts say those revenues could ebb. Over a full year, net tariff revenue might reach around $300 to $360 billion at the current rate, whereas interest on the debt is on track to exceed $1 trillion for the year.

Beyond the disparity between the sums involved, there’s a deeper issue—tariffs are not free money. They are ultimately paid by American importers (and often passed on to consumers via higher prices). Economists say higher prices could slow growth, which in turn could shrink other tax revenues. They also invite retaliation against U.S. exports, which could potentially harm American businesses. Even at record highs, tariff revenues are just a small slice of the fiscal pie, accounting for around 2–3% of total federal revenue, while major programs like Social Security, Medicare, and defense far outweigh it. In fairness, every dollar helps. Tariffs might modestly slow the pace of borrowing, but, as Lachman pointed out, using tariffs as a core debt solution seems more like a political talking point than a serious fiscal strategy. No single policy gimmick, whether tariffs, asset sales, or printing money, is going to magically pay off $37 trillion.

The Growing Burden of Interest

Interest has become the clearest, most inescapable cost of America’s towering debt. As balances swell and rates climb, the federal government must devote ever larger sums simply to service what it already owes. This year, interest is projected to cost about $1 trillion, which would place it ahead of national defense and Medicare, second only to Social Security. More of what taxpayers send to Washington now goes toward paying yesterday’s bills, rather than funding new services or long-term investments.

Why has interest become such a budget buster? For one, the sheer size of the debt means even moderate interest rates translate into huge interest totals. And lately, interest rates are no longer moderate. Over the past two years, the Federal Reserve has lifted short-term rates from near zero to around 5%, and longer-term Treasury yields have moved higher as well. New borrowing now carries a much steeper coupon, and existing bonds that mature must be refinanced at today’s rates. The strain shows up in the monthly ledger. Of the roughly $339 billion in revenue collected in July 2025, about $91 billion went out the door to cover interest, more than one dollar in four. Even by a stricter net measure, the interest bill still ran near $61 billion that month. Either way, the government is treading water and paying for the past rather than building the future.

The burden of high debt and interest doesn’t stay confined to a ledger; it spills into the broader economy. Michael Peterson, CEO of the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, explains that heavy government borrowing puts upward pressure on interest rates, “adding costs for everyone and reducing private sector investment.” When the government devours so much of the available lending capacity, businesses and consumers may face higher rates on mortgages, car loans, and business loans. The Government Accountability Office has warned that an unchecked path might produce a vicious cycle in which more debt begets higher interest costs, which then requires more borrowing that drives interest costs higher still. If that loop tightens, long-run growth could fade, and financial stability may look shakier.

The trend is clear. In 2017, net interest was roughly $250 billion. By 2022, it had cleared $400 billion. Now the annual tab is approaching $1 trillion. Those dollars are not being used to resurface roads or modernize schools. They flow to bondholders, including a sizable share abroad (from China to pension funds in Europe). This reality has led some national security experts to express concern: a heavily indebted America, constrained by debt payments, may have less room to respond to crises or sustain defense outlays when they matter most.

President Trump, for his part, has been preoccupied with the cost of interest, and some claim it’s not always for the better. Frustrated by how much federal revenue is being eaten by debt service, he has urged the Fed to “force down interest rates so debt is cheaper.” The appeal may sound simple, but the tradeoffs could be severe. The Fed is tasked with maintaining price stability and achieving maximum employment, not with accommodating fiscal excess. Economists warn that lowering rates for budget relief might offer brief savings but could stoke inflation, distort asset prices, and ultimately lead to higher borrowing costs or a weaker dollar. That would leave taxpayers paying more, not less.

For most families, debt often remains invisible until it begins to impact everyday life. No bill arrives with your $108,000 share. But you may notice that interest rates on mortgages or student loans are higher, or that the government is slower to invest in that new highway or veterans’ clinic in your town. Economic growth may be slower in a high-debt environment, translating to fewer job opportunities or stagnant wages. If confidence in U.S. finances erodes, there’s even the risk of a fiscal crisis, as a sudden spike in interest rates or a sharp drop in the dollar’s value could trigger a broader economic downturn. While the U.S. has not reached that point, the warning signs are growing. In 2023, Fitch Ratings cited “expected fiscal deterioration” and the “high and growing debt burden” as reasons for its decision to downgrade the U.S. government’s credit rating from AAA to AA+. It was only the second time in modern history a major agency downgraded U.S. debt (the first was S&P in 2011).

Confronting an Unsustainable Path

Virtually everyone across the ideological spectrum now agrees on one thing: the current debt trajectory is unsustainable. As the bipartisan Peterson Foundation put it, “America’s high and rising debt…threatens our economic future”. The disagreement is over what to do about it and how urgently to act. So far, the political system has mostly delivered gridlock or half-measures. The debt problem is politically thorny because it ultimately revolves around making painful choices, such as raising taxes, cutting popular spending, or a combination of both. No politician relishes those options, so the can gets kicked down the road. But all roads eventually come to an end.

“Hopefully this milestone is enough to wake up policymakers to the reality that we need to do something, and we need to do it quickly,” Maya MacGuineas implored when the debt hit $37 trillion. It was a plea tinged with frustration as similar alarms have been sounded at $20 trillion, $30 trillion, and every step along the way, usually to little avail.

Economist Wendy Edelberg of the Brookings Institution points out that recent policy choices have set the stage for even more borrowing ahead. “[It] means that we’re going to borrow a lot over the course of 2026, we’re going to borrow a lot over the course of 2027, and it’s just going to keep going,” she said, referring to the trajectory baked in by current tax and spending laws. In other words, unless changes are made, trillion-plus deficits will be a recurring feature of each coming year, pushing the debt to ever more staggering heights. By the end of the decade, at the current course, the U.S. could be staring at $50 trillion in debt.

Amid rising concern over the national debt, Washington is again floating the idea of a fiscal commission, which would serve as a bipartisan panel to help reduce the deficit. In theory, the commission could craft a comprehensive agreement on taxes and spending and send tough recommendations to Congress for a straightforward up-or-down vote. On paper, it sounds tidy, even promising. But if history is any guide, talk of a grand bargain is likely just that—talk. Any serious fix would require something more complicated than a panel’s report. It would demand sustained bipartisan cooperation and public buy-in that could last through more than one news cycle. Whether this idea gains traction remains to be seen, but it underscores a hard reality: everyday legislative politics aren’t working.

In the end, the nation’s $37 trillion debt powder keg isn’t just an abstract figure. It’s a reflection of the choices, some unavoidable and some avoidable, that U.S. policymakers have made. It’s a claim on the country’s future output; a mortgage on tomorrow that today’s Americans are taking out. Every additional trillion in debt “crowds out” a bit more of the future, as Michael Peterson described, creating “a damaging cycle of more borrowing, more interest costs, and even more borrowing“.

If the debt path remains steep, households may want to take ballast. Gold has long served as a store of value when fiscal anchors look loose and confidence feels shaky. It does not rely on a promise to pay. It carries no credit risk. And in periods when deficits swell, inflation expectations drift, or the dollar weakens, gold tends to maintain its purchasing power, while most assets fluctuate. That does not make it magic, but it does make it useful. Over long stretches, gold often moves independently from stocks, bonds, and real estate. That low correlation might soften portfolio drawdowns when policy stress rises. In severe market breaks, gold can act as insurance, not because it always surges, but because it may resist the same pressures that drag other assets lower. With interest costs likely to climb and politics stuck in neutral, that kind of diversification could prove even more valuable.